"American Knees" and "Americanese"

The racial politics of "intra-Asian" miscegenation

By William Wetherall

First posted 20 July 2006

Last updated 1 August 2006

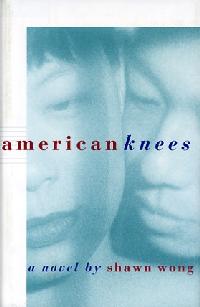

Shawn Wong, American Knees, 1995

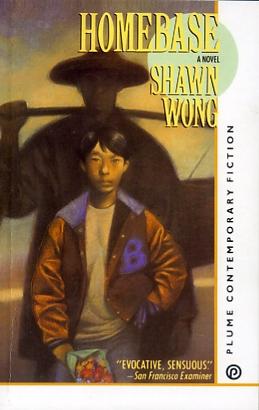

Shawn Wong, Homebase, 1979

American KneesShawn Wong A structural reading of the novelI am not in favor of reading fiction as biography. I certainly would not want anyone who reads my stories to equate their characters with me in one incarnation or another. Yet all writers I have known, including myself, who I've come to know fairly well, disguise parts of themselves in many of their otherwise imaginary characters. They also draw from the lives of those they know. American Knees is full of elements that reflect Wong's life at personal, generational, and professional levels. Professionally Wong is a professor of English who, from the very start of his literary career, back in the late 1960s and early 1970s, has been deeply involved in what can still be called an "ethnic studies movement". Wong undoubedly puts ideas into the brain of his protagonist -- Raymond Ding -- that he, Wong, might not himself embrace or endorse. But there is little doubt that Raymond Ding's committment to improving the social status of Asian Americans in their own eyes -- as well as in the eyes of the larger, sometimes inclusive, sometimes exclusive mainstream -- reflects Wong's personal goals as a writer, educator, and activist. While Wong may regard himself as an American of Chinese descent, he has also had to think of himself as an American of a more diffuse, geographically and politically defined Asian ancestry. As a teacher of general courses on Asian American literature, too, he has had to become familiar with the histories of all putatively Asian American ethnic groups. It is through his eyes as an Asian Americanist that Wong is able to lace American Knees with all the benchmarks of Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese American history and contemporary life. To be continued. |

AmericaneseWhat changed in the film and whyBy William WetherallAmerican Knees Productions The following "Editorial Review" on Amazon.com shows what Shawn Wong's very interesting but less than perfect novel, and its less interesting but more problematic film version, are up against in the racialist world that makes both inevitable.

There is nothing "light-hearted" about Wong's romantic comedy. Every laugh is a calculated break in Wong's ultraserious effort to dramatize the racialist concerns of his characters as human if not also futile. The protagonist's name is Raymond Ding, not Deng Xiaoping. Raymond, his father, his lovers, and his friends are Americans. They are Americans by birth and would cringe at being called "half-American" simply because they might, by their own or someone else's racialist measure, also be "Asian" or "half-Asian". To be continued.

|

HomebaseShawn Wong 112 pages, softcover With a new introduction by the author This novella, in six short chapters, was first published by Ishmael Reed, the founder of Yardbird Reader, in 1979. Parts of the story go back to work Wong contributed to publications like Aiiieeeee! (1974) and Yardbird Reader Volume 3 (1974) in his more radical youth. For reviews of these and related publications, see Asian Americans under the "Identity fiction" section of the Bibliography feature of this website. Solberg states that "Homebase is where we come from, where we go back to" and says Wong's novel is about America -- "America as homebase for four generations of one Chinese-American family" (page 99). The first-person protagonist is a young man who was orphaned at age 15, since which time has been a journey, part of it the sort of hippy trek that Wong and some of his Berkeley and other writer friends took, literally and literately, in the 1960s and 1970s. RainsfordThe third paragraph of Chapter One says everything about Wong's fluid and inviting style (Plume edition, pages 1-2).

Later Wong meets an old Indian man in whom he sees his grandfather's face (Plume edition, pages 82-83).

This stretch of the novel, as the story winds both up and down, gets better and better. This is one of my favorite stories, by any author. |