Tokyo dolls and affairs

Two pulp thrillers by John McParland

By William Wetherall

First posted 1 September 2006

Last updated 1 June 2010

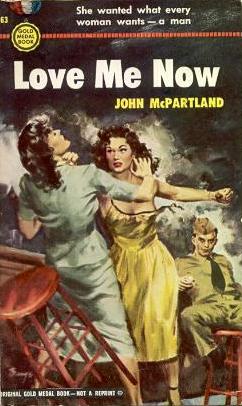

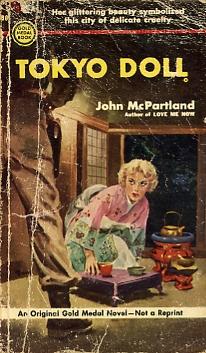

John McPartland, Tokyo Doll, 1953

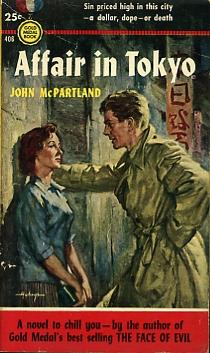

John McPartland, Affair in Tokyo, 1954

Linguistic note The semantic wrinkles of "jo"

John McPartland John McPartlandJohn McPartland (1911-1958) lived only a few years after becoming one of Gold Medal's most popular authors of the sort of sexy action thrillers now called "noir fiction". He wrote eleven such stories, beginning with Love Me Now (1952) and ending with The Last Night (1959), which was published posthumously. Only his seventh novel, No Down Payment (1957), came out in hardcover -- a measure of recognition that he had become more than a mere "paperback" writer. Like many writers of pulp thrillers, which rarely came out in more than multiple editions, McPartland was prolific, and most of his stories were close to the contemporary bone. He turned out nearly two books a year, and the lag between their fictional plots and real life was seldom more than a year or two. The Last Night, which came out in 1952, features a court-appointed attorney who has to defend a beatnik woman against a murder charge. Tokyo Doll and Affair in Tokyo, published in 1953 and 1954, are respectively set during and shortly after the Korean War, which unfolded from mid 1950 to mid 1953. |

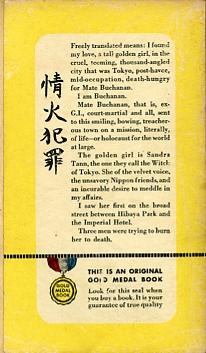

John McPartland Blonde geisha with gray eyesAs is clear from the cover, not all geisha in Japan have black hair and dark eyes. McPartland beat the film "My Geisha" (1961) to the punch by several years, and Shirley MacLaine was ahead of Liza Crihfield (Dalby) by about a decade. McPartland, for that matter, was hardly the first to contrive a blonde, gray-eyed geisha. The front cover tells us that "Her glittering beauty symbolized this city of delicate cruelty". The blurb on the back begins with a "free translation" of the characters 情火犯罪 (see image).

How could any red-blooded browser at a paperback rack resist? Tokyo Doll is full of mid-Korean War, late-Occupied Japan ambiance that would strike a chord with tens of thousands of U.S. Forces personnel and American civilians in the country at time. |

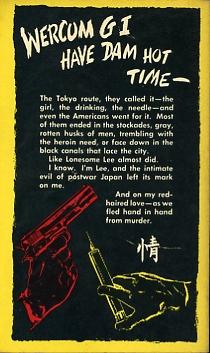

John McPartland Affair in Tokyo"Sin priced high in this city -- a dollar, dope -- or death" claims the cover of Affair in Tokyo. The characters on the vertical sign suggest that the cover artist didn't know much about calligraphy. The character 情 appears on the back above a hand with a syringe and needle, and a piston in a hand, below this teaser.

"I know. I'm Lee," has the same narrative ring as "I am Buchanan." In other ways, too, Affair in Tokyo has overtones of Tokyo Doll -- as though McPartland himself stuck in a rut of interest in American men who had affairs with American dolls in Japan. |

Linguistic noteThe semantic wrinkles of "jo"THIS NOTE WILL BE EXPANDED INTO The characters 情火犯罪 on the back cover of Tokyo Doll are brushed correctly if not very artistically. The 情 on the back cover of Affair in Tokyo is a cut and paste from the 情火犯罪 calligraphy. This is worth pointing out because graphic designers infatuated but unfamiliar with characters often mangle them. The characters on the front cover of Affair in Tokyo are a case point. How Gold Medal's graphic designers -- if not McPartland himself -- came across the expression 情火犯罪 is probably unanswerable. The history of 情火, though, is somewhat knowable. Crimes of passion情火犯罪, though not an established expression, is both plausible and clear. An extensive search of Japanese sources would probably come up with an example or in a work of non-fiction if not a novel.The characters read "joka hanzai", which means "crime of passion" -- though "crime of passion" is usually 情痴犯罪 (jochi hanzai) or 痴情犯罪 (chijo hanzai), but also 激情犯罪 (gekijo han), or even 痴情犯 (chijo han) or 激情犯 (gekijo han) in Japanese. All of these compounds have phrasal variations using the verb よる (yoru) and the postposition noun-marking adverb に (ni), as in 激情による犯罪 (gekijo ni yoru hanzai) or "crime due to passion". The most common expression in Chinese seems to be 激情犯罪 (ji1qing2 fan4zui4). 激情 (C. ji1aing2, J. gekijo) means a "strong passion" such as an impulse of jealous rage that triggers murder, arson, and other acts of violence. Flames of passion犯罪 is the standard word for "crime" while 情火 is also an established compound meaning the "flames" or "fires" of a passion so strong they cannot be put out. 情火, though, is not the word most generally be used in Japanese where one would say passion in English. It implies a burning and uncontrollable lust more than merely strong sexual emotions. 情火 is therefore most likely used in titles of novels and movies about burning desire. It is the Japanese title of an August Strindberg (1849-1912) story translated by Yoshida Hakko in 1908 (Shinshicho, January to March). It is also the title of an 11-reel Shochiku film released in 1952. However, 情火 is most likely used in association with an agent or locale in the translated titles of movies.

Synonymous metaphors情火 is not even the most common metaphor for passion as a flame or fire. That honor goes to 情炎 (joen), which is not equivalent to 情火 metaphorically, but is also more familiar and productive in titles of movies and novels. Some writers have swapped the two. Kayama Shigeru (1904-1975) later published タヒチの情火 (1950) [Tahichi no joka, Passion in Tahiti], a short story, as 楽園島の情炎 (1959) [Rakuento no joen, Passion on paradise island].

Other writers have used both. Suehiro Kei (b1940), who likes two-character titles that allude to sexual craving, has published several erotic suspense thrillers with 情 (jo, passion) in their title, including 情炎 in 2002 and 情火 in 2006. Both of these novels were brought out in original pocketbook editions by Futabasha, which specializes in books and magazines on the risque side of popular. |