Realism, revisionism, and racialism

Paranoia and censorship in Crichton's 'Rising Sun'

By William Wetherall

This page consists of three articles:

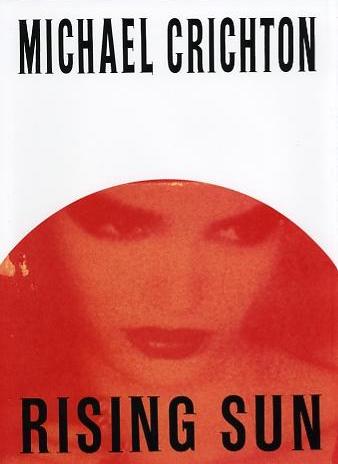

1. Old politics, new anthropology -- A review of Rising Sun

2. Doctoring 'Rising Sun' -- The Japanized translation

3. Censoring 'Rising Sun' -- Hayakawa Shobo cuts "burakumin"

Old politics, new anthropology

A review of Michael Crichton's 'Rising Sun'

By William Wetherall

A version of this article appeared as

"Crichton's fiction merges realism, revisionism and racialism"

with Mark Schreiber's "Deceit and betrayal: old gist for new mill"

under the general title The house of 'Rising Sun' in

The Japan Times, 12 August 1992, page 17 (Focus)

Michael Crichton Disclosure 1 -- I am a pulp lit junky, and a Michael Crichton fan. Andromeda Strain, Terminal Man, and Jurassic Park are out of this world, yet very much a part of it. Binary and The Last Tomb (two of the many thrillers that Crichton has written as John Lange) are studies in well-crafted suspense with sprinkles of food for thought. Disclosure 2 -- I have one foot in the "revisionist" camp. The United States has a "Japan problem" with an important American-made component that can only be solved by giving domestic interests more attention: the kinds of national interests described in Rising Sun. Disclosure 3 -- My other foot is critically free. And it wants to kick Crichton in the pants for spoiling the better story that Rising Sun would have been if even one of its American characters had been more knowledgeable about Japan and less racialist about the world. Revisionist messageBefore kicking Crichton, let me give him his due. Rising Sun is a par-for-the-course thriller with a serious message. The story is told through the eyes and ears of Peter Smith, a mild-mannered police officer who represents the politically naive American everyman. Through contact with other characters, but mainly with the central character -- is senior in rank John Connor, a skeptical lover of Japan -- Smith (and readers who are open to the premise of the book) comes to realize that Americans must balance their technological and industrial accounts at home. Connor, whose knowledge of "Japanese language and culture" is such that he "always knows exactly what he is doing" when working with "the Japanese" (p. 12), sums up Crichton's premise in two lines (p. 251): "If you give up control of your own institutions you give up everything. And generally, whoever pays for an institution controls it." Connor believes that "Japan" and "the Japanese" are what they are, and that "the Japanese system is fundamentally different" (p. 325). This means that Americans must learn to deal with Japan strategically, as one deals with anything one cannot change but has to coexist with. In the epilogue to his Japanese translation of Rising Sun, Sakai Akinobu observes that "the Japanese" (Nihonjin) are like the "unknown" and "different" entities that challenge the heroes in Crichton's other thrillers. "Japan" and "the Japanese" are equivalent to the Jurassic Park dinosaurs that over-confident genetic engineers succeeded in cloning but failed to contain on a remote island. Crichton views "Japan" and "the Japanese" as just another version of the human condition. The Japanese version is to be respected, understood, and dealt with in a realistic way that does not undermine American society. The American version will survive, Crichton states in his afterword, only if Americans get their act together, and remember that "the Japanese" are not their saviors, but their competitors. Crichton's political message is not as alarmist as the title, Rising Sun, implies. Yet Falling Eagle would also have failed to reflect the quieter tones of faith in the future that come at the end. While much of the story focuses on what Crichton feels is wrong in the US-Japan relationship, the story concludes with a hopeful conversation between officer Smith and a Japanese businessman. The future of the international relationship is left uncertain. But Crichton clearly believes that it would improve -- if put on a truly mutual foundation. Unrevised imageUniversity of California political scientist Chalmers Johnson rightly points out that attacking Rising Sun as a bearer of bad news will not make the bad news go away. He also cogently argues that calling critics of Japan or critics of America's Japan policy "Japan-bashers" or "racists" is a fascist act in that it favors ideological correctness over truth-seeking analysis and thought. Two problems arise here: (1) Rising Sun is, in fact, flawed by Crichton's "national character" anthropology, and by his racialist view of Japan and the United States -- and to overlook these flaws is to ensure that the bad news he properly bears is going to get worse; and (2) some of the "politically correct" critics who have called Rising Sun "racist" have shown themselves to be no different from Crichton -- that is, normal. If the heroic Connor is Crichton's ideal of an American "Japan" handler, then it is understandable why the US-Japan relationship is in trouble. The problem is not Connor's common-sense "revisionism", but his view of "Japan" and "the Japanese" as a culturally programmed race. Crichton seems to endorse this view, for he claims that he created Connor as "the voice the reader is asked to believe." Crichton, with his background in science and medicine, has been able to breathe considerable authenticity into his techno thrillers, for he knows his settings, and the language and behavior of his characters. This credibility is absent in Rising Sun, as it is in most works of English-language popular fiction that feature the mysterious East or the inscrutable Oriental in the West. Had Rising Sun appeared under a pen name, it would be gathering dust on a shelf-full of similar potboilers. As a cardboard character, John Connor is like countless others in entertainment fiction. And his "Japan is" and "the Japanese are" idiom is the depressingly familiar standard in both mass media and academia. Such common features of entertainment fiction would be tolerable in Rising Sun if Crichton were only a story teller. But he also claims to a bearer of a sophisticated revisionist message. Unfortunately, this message is left unbalanced by a view of "Japan" and "the Japanese" that reduces this large, diverse, complex country and citizenry to a tourist guidebook stereotype. The specter of raceCrichton has been called a "racist" but he is not one. Rising Sun does not advocate treating people differently because of race. And in a Los Angeles Times interview with novelist T. Jefferson Parker, Crichton said that "to make divisions based on race is not to anyone's benefit." Crichton is concerned about "nationality" to the extent that it is a real political unit. Also in the Los Angeles Times interview, he said that "nationality" as a "legal system" will continue to be "inevitable and necessary" despite the movement toward a world economy. But in Rising Sun, Crichton encourages the labeling of people on the basis of their perceived race, in a way that ignores citizenship. This is what I mean by "racialism". The distinction from "racism" is important, for it gets at the nexus of what is wrong in descriptions of "Japan" and "the Japanese" in the context of "America" and "Americans". Despite Crichton's definition of "nationality" as a legal entity, Rising Sun portrays "Japan" and "the Japanese" not as a state and its citizenry, but as a race; most major characters in the book compare "the Japanese" with "white" and "black" -- though in Japan as a legal nation, Japanese come in all colors -- black, white, yellow, you name it. Peter Smith sees "only" three whites in a college science class (p. 177). "A class like Physics 101 doesn't attract Americans," the professor explains. What he says next reinforces the impression that the "Asians" ("nearly everyone in the class") are foreigners. No heed is given the probability that most of the "Asians" are Americans. Connor is said to have been the only officer who spoke fluent Japanese "back in the 1960s . . . even though Los Angeles then had the largest Japanese population outside the home islands" (p. 12). This is true only if São Paulo and New York are ignored; or if "Japanese" is a race and "Japan" is regarded the true "home" of Japanese Americans. Connor twice remarks to Smith that "the Japanese" are "the most racist people" on earth (pp. 219, 327). He supports this by relating to Smith some unpleasant experiences he has had, but in a manner that projects his paranoia and exaggerates reality. Connor fails to tell Smith that, in Japan, citizenship is not based on race or ethnicity. And he fails to observe that Japanese, regardless of their race or ethnic ancestry, are treated at least as equally under Japanese laws as Americans are treated under US laws. Racism (which racialism undoubtedly encourages) is undoubtedly rampant on streets in Japan. But are racial traits less likely to elicit evasive, exclusive, patronizing treatment in America's jungle? In any country's social wilds, individuals discriminate; but Crichton wants us to believe that "Japan" and "the Japanese" commit such acts. The Japanese American Citizens League (JACL), an American civil rights organization, exists mainly because most Japanese Americans have faced, and continue to face, racist treatment that is exacerbated by racialism in US-Japan relations. And JACL's national president, Cressy Nakagawa, reportedly said that Rising Sun is "tantamount to racism"; and he lamented that, "From the novel, I don't know how you could make the distinction between Japanese and Japanese Americans." Perhaps Crichton got his racialist cues from the pages of Pacific Citizen (PC), JACL's weekly newspaper. Nakagawa himself, speaking on behalf of Japanese Americans, has referred to "Japanese" as "of our own ethnicity" and "of our race" (PC, 29 June 1990). And a PC editorial associated American filmmaker Steven Okazaki with "Japanese" five times (in contrast with "Caucasian") -- without once calling him an "American" (29 March 1991). Such racialism is so innocently habitual and commonplace that most people are unaware of it. Of course, Nakagawa is no more a "racist" than Crichton. But when the voices of such influential Americans talk about "Japan" and "the Japanese" as a racial monolith, they overlook the racial and ethnic diversity among not only Japanese and others in Japan, but people of Japanese ancestry in America and other countries. It is arguably this banal orthodoxy of racialism, even more than our understanding of the political and economic aspects of the US-Japan relationship, that desperately needs revision -- not just in popular fiction, but in scholarship and journalism. Had Crichton created a wiser, more civic-minded hero, Rising Sun would have been a remarkable book. William Wetherall is a free lance researcher and writer who specializes in suicide, ethnicity, and popular fiction. He has lived in Japan for twenty years. |

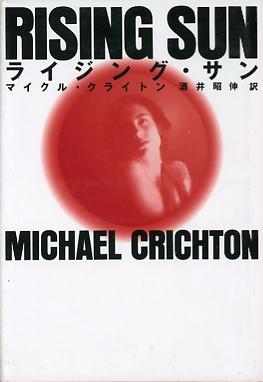

Doctoring 'Rising Sun'

The Japanized translation

By William Wetherall

First written in July 1992

First posted 10 January 2006

Last updated 21 July 2024

Maikuru Kuraiton [Michael Crichton] Translating can be a mind-bending process, especially when one editorial objective is to "correct" the original. The Japanese version of Rising Sun, Michael Crichton's controversial thriller about American complicity with Japanese business practices in the United States, has undergone minor cosmetic surgery. But the standard of skin-deep beauty has been more political than truthful. One line of the original does, to Crichton's credit, recognize that, in principle, Japan is a land of equality. Theresa Asakuma, a Japanese graduate student, tells the narrator, officer Peter Smith, that "In Japan, the land where everyone is supposedly equal, no one speaks of burakumin" (p. 261) -- referring to present-day Japanese who consider themselves the descendants of outcastes emancipated by law in 1871. As though to vindicate Asakuma, the publisher, Hayakawa Shobo, which in the past twenty years has published at least fifteen Crichton (alias Lange) titles, asked Crichton for permission to delete this entire sentence, and all other mentions and details about burakumin, from the translation -- and to make other changes. Crichton consented. Several other sentences and words, most of them bitterly spoken by Asakuma when she dramatizes to Smith how she had been treated because of her physical deformity and her different racial characteristics, were also deleted or significantly changed in the translation. Most expressions that have been cut or paraphrased are found on lists of "discriminatory words" that are considered unfit to print or utter in Japan because they might offend someone. Crichton, though, did not use these words to discriminate against anyone; he put them into the mouths of characters who had experienced discrimination, and who were explaining how they had been treated and how they felt about it. Several of Crichton's personal and company names, and many of his Japanese language expressions, have been changed because they were too strange or simply wrong. For example: Kasaguro Ishigura, the principal Japanese character in the English edition, is Masao Ishiguro in the Japanese translation. Hamaguri, a fictional corporation, became Hamaguchi -- as it did in Jurassic Park, also translated by Sakai Akinobu. An AIDS joke, butting US sailors in Japan, attributed in the first English edition to former prime minister Noboru Takeshita, has been anonymously attributed in the Japanese edition to "a major politician". All "Japanese" names -- even the names of the most famous people, places, and corporations -- names that would ordinarily be written in Sino-Japanese characters -- have generally been transliterated into the katakana syllabic script that is used to transcribe foreign words. Such emphasis seems to suggest that there is something awkward or alien about "things Japanese" as seen, heard, or contemplated by narrator Smith. Of course, this added "we/they" consciousness was neither the intention nor the effect of Crichton's story as told in English. Translator Sakai wrote in his afterword that factual errors are being corrected in each printing of the English edition, and that such changes that he knew of are reflected in his translation. He also said that Crichton was consulted about and permitted the "corrections" in the translation, and that "the [corrections] that we made will to some extent be reflected in [future printings of of] the original." Sakai calls this process of initiating "corrections" of an American writer's view of Japan, through translation into Japanese, "meaningful". It is also meaningful, and more telling, that Hayakawa Shobo is refusing to comment on the cuts and changes it made in Rising Sun. Before refusing to comment, however, the editor in charge of the translation admitted that Hayakawa Shobo decided to cut all references to burakumin entirely on its own: there was no contact with the Buraku Liberation League (BLL), which has a political interest in such matters. Komori Tatsukuni, BLL's secretary general, is on record as being against both discriminatory writing and self-censorship. Apparently he would prefer that publishers contact his organization for guidance in how to "correct" (rather than simply delete) possibly inaccurate or offensive words or passages. Komori, though, has not responded to a written request for his opinion about Hayakawa Shobo's self-censorship. BLL and Hayakawa are not, however, strangers. In 1990, BLL strongly protested a number of statements in Karel van Wolferen's The Enigma of Japanese Power, which Hayakawa had published in a verbatim Japanese translation. Apparently this experience had the effect of motivating Hayakawa to avoid future problems with BLL by resorting to self-censorship. If so, then Hayakawa's version of Rising Sun ironically supports van Wolferen's thesis about how publishers in Japan are apt to respond to real or imagined threats from pressure groups. |

Censoring 'Rising Sun'Hayakawa, BLL, and "burakumin"By William Wetherall

First written in August 1992 The Japanese translation of Rising Sun, Michael Crichton's controversial crime thriller set in the midst of American complicity with Japanese business practices in the United States, has undergone minor cosmetic surgery. One result of the cutting and stitching is a less explicit face on the subject of social discrimination in Japan. The English version has two paragraphs in which Theresa Asakuma, a Japanese graduate student at an American university, tells narrator Peter Smith, a police officer, as follows (p. 261): "You know what the burakumin are?" she said. "No? I am not surprised. In Japan, where everyone is supposedly equal, no one speaks of burakumin. But before a marriage, a young man's family will check the family history of the bride, to be sure there are no burakumin in the past. The bride's family will do the same. And if there is any doubt, the marriage will not occur. The burakumin are the untouchables of Japan. The outcasts, the lowest of the low. They are the descendants of tanners and leather workers, which in Buddhism is unclean." Smith says "I see." And Asakuma, whose right arm is deformed, and whose father was a "black man" (her mother is not described), continues: "And I was lower than burakumin, because I was deformed. To the Japanese, deformity is shameful. Not sad, or a burden. Shameful. It means you have done something wrong. deformity shames you, and your family, and your community. The people around you wish you were dead. And if you are half black, the ainoko of an American big nose . . ." She shook her head. "Children are cruel. And this was a provincial place, a country town." The Japanese versionIn the Japanese version, published by Hayakawa Shobo -- which over the past two decades has brought out translations of at least fifteen of Crichton's stories (half of them written under a pen name) -- these two paragraphs have been radically cut and changed as follows (p. 395): "In Japan, okay? In that country where everyone is supposed to be equal, there are various kinds of groundless discrimination (konkyo no nai sabetsu). [Japan] gives birth to [kinds of] discrimination about which the lack of understanding is incredible (murikai ga hidoi sabetsu)." Smith says "I didn't know that," and Asakuma continues: "Even [because of] this right hand, I was teased (ijimerareta) a lot. On top of that, being half black (hanbun kokujin), and with an un-Japanese face (Nihonjin-banare shita kao) . . . ." Theresa shook her head. "Children are cruel. Moreover, it was a country town." According to the epilogue to the Japanese version, and to Hayakawa editors, the president of the publishing company and the translator together visited Crichton in California, to obtain his permission to make cuts and changes in the above and other passages. Apparently Crichton agreed to Hayakawa's request on the grounds that such passages were not important to the main story; and apparently he accepted the publisher's view that a faithful rendering of such passages would invite undesirable repercussions in Japan. In a written reply to a formal query from my research assistant, representing me, Hayakawa refused to comment on the above (and other) passages that were subjected to cuts and changes. On the telephone, however, the editor in charge of the Japanese translation admitted that Hayakawa had acted on its own, without any contact from the Buraku Liberation League (BLL). BLL responseFor the past seventy years, BLL and its precursors have actively protested how some publications have portrayed burakumin ("community people"), referring to Japanese who regard themselves as descendants of outcastes emancipated by law in 1871, and may live in urban or rural neighborhoods that some people continue to discriminate against. Komori Tatsukuni, a member of the House of Representatives, and BLL's Secretary General, was less reluctant than Hayakawa to elaborate, in writing, his opinions on the above changes and cuts. Komori is opposed to "self-censorship" (jiko ken'etsu) if the term means that a publisher abbreviates or changes the original without the permission of the writer and translator. However, he added, the mutual conviction that abbreviations and changes are necessary should be made on the basis of sufficient discussion between these parties. Provided with copies of the original English and the Japanese version of the above paragraphs for comparison, Komori said that the original should have been translated as it was. He especially seemed to lament the dropping of the lines on deformity and shame, which he thinks describe the discriminatory thinking in Buddhist ideas about karma (go) and rebirth (rinne) that "many Japanese have been invaded by." Asked whether he thought Hayakawa should have sought the opinions of BLL, he said, very plainly, no: for "strictly speaking, Hayakawa is free [to do as it did]." He qualified this, however, by listing two reasons why a publisher might seek BLL's opinion. First, in the censorial sense, the publisher does not want to cause trouble with BLL. Second, it just wants to know, "Will people who are discriminated against be hurt by this writing?" Komori calls the first motive a "shameful attitude" (haji subeki taido); while the second, as a sincere regard for the people affected, "is a way of life that [I] can agree with (kyomei dekiru ikikata)." Past encountersNo one will ever know whether BLL would have denounced an unexpurgated Japanese translation of Rising Sun. But all information at hand suggests that Hayakawa did not discuss with Crichton the history of its motivation to cut and change especially the lines on burakumin. And so what Hayakawa did, with Crichton's permission, seems to constitute "self-censorship" even in Komori's narrow definition of the term. Furthermore, the background of Hayakawa's behavior implies that the publisher acted out of what Komori has labeled a "shameful" motive. For BLL and Hayakawa are not, it turns out, strangers. In late 1990, BLL strongly protested a number of statements in Karel van Wolferen's The Enigma of Japanese Power, which Hayakawa had published in a verbatim Japanese translation that reached book stores uncensored. Apparently this experience had the effect of motivating Hayakawa to avoid future problems with BLL by censoring everything that might offend anyone. If so, then Hayakawa's censoring of Rising Sun tellingly supports van Wolferen's thesis about how publishers in Japan are apt to respond to real or imagined threats from pressure groups. In permitting Hayakawa to delete all mention of the burakumin, Crichton ironically became an accessory to the very crime of silence that he, as Theresa Asakuma's creator, troubled himself to have her describe in the English version: "no one speaks of burakumin." Censorship trendThis crime of silence is pervasive. Discussions of burakumin but also of Koreans and Chinese, in relation to criminal gangs, have been cut from the Japanese "translation" of Alec Dubro and David Kaplan's highly regarded Yakuza, which appeared in the spring of 1991 after years of press rumors that no Japanese publisher had the courage to market a faithful translation. Some publishers even pay big bucks to avoid risk of controversy. Late in the autumn of 1991, the publishers of Winds, JAL's inflight magazine, scrapped an entire issue that had just been printed and was ready for distribution to planes. Copies already mailed to subscribers were followed by a letter asking for their return because of "sensitive" material. Christine Chapman's "Japanese Detective Story: True Tales of Illicit Affairs, Gutter Gossip and Bad Blood" was replaced, and the entire issue was reprinted at a rumored cost of one-million dollars. Chapman's story, with a very subtle but significant revision in its paragraph about family background investigations and burakumin, was reincarnated as the "Private Eyes" cover story of the February 1992 issue of Tokyo Journal. It is possible that Winds blew all that money merely because its image mongers wanted to spare JAL's English-reading passengers a look at Japan's sordid underbelly -- at least until they landed at Narita and stayed in town long enough to sneak a look at Tokyo Journal. This was not the first time that Tokyo Journal resuscitated a piece too hot for Winds; nor were such resuscitations a coincidence, for the editor of Winds was then also an editor of Tokyo Journal. But the Winds case seems to fit the pattern of burakumin (and BLL) avoidance exemplified by the Japanese version of Yakuza -- and by the translations of a long list of other works, including James Clavell's Shogun and Edwin Reischauer's The Japanese. Unfortunately, this trend of unmentionability -- this irrational fear of speaking of burakumin -- has been kept alive by Hayakawa's handling of Rising Sun. |