Chinese boxes

Some open, some don't

By William Wetherall

First posted 15 August 2006

Last updated 5 September 2006

Introduction

Novels and short stories

Marian Bower and Leon M. Lion, The Chinese Puzzle, 1919

Captain W.E. Johns, Biggles' Chinese Puzzle, 1955

Katherine Wigmore Eyre, The Chinese Box, 1959

Robert Martin, The Chinese Box, 1960

John Creasey, The Baron and the Chinese Puzzle, 1965

Gerald Chan Sieg, The Chinese Christmas Box, 1970

Marjorie McEvoy, The Chinese Box, 1973

Christopher New, The Chinese Box, 1975

Marele Day, The Case of the Chinese Boxes, 1990

Chris Auer, The Chinese Puzzle Box, 2005

Films

Wayne Wang, Chinese Box, 1997

"Chinese" puzzle boxes

"Chinese box" and "Chinese puzzle box" -- and sometimes just "Chinese puzzle" -- are synonymous with mystery and suspense, an enigma or a riddle. They suggest something complex and difficult, or hidden and secret, as in boxes within intricate boxes.

Some stories with such phrases in their titles are set in China and some have nothing to do with China. Most involve actual puzzle boxes with secret compartments containing something someone will kill for. A few have nothing to do with such boxes other than to suggest that China itself is a puzzle for an outside world that tries in vain to discover its hidden secrets.

Made in Japan

If "Chinese puzzle boxes" symbolize the inscrutable Orient in the Occidental world, they reflect more the capacity of the Occidental world to confuse and conflate Chinese, Korean, Chinese, and other Asian countries, languages, peoples, and cultures.

A puzzle box bought in a curio shop on Grant Street in San Francisco in the 1950s and 1960s was Chinese. That it had been made in Japan simply meant that Japanese had started producing Chinese puzzle boxes.

Serious students and collectors of such boxes have issued all-point-bulletins for the whereabouts of a puzzle box that is truly Chinese. There are Chinese boxes, and Chinese puzzles, but are there Chinese puzzle boxes? Apparently only in the Occidental imagination.

Property of fans

While this may seem a prime example of Orientalism, consider the fact that "culture" is never a private property. The British writer and filmmaker should now (Barker's website).

The extraordinary event is this: that the moment you make a story or create an image that finds favour with an audience, you've effectively lost it. It toddles off, the little bastard; it becomes the property of the fans. It's they who create around it their own mythologies; who make sequels and prequels in their imagination; who point out the inconsistencies in your plotting.

The most famous "Chinese puzzle box" is fiction is the "Lemarchand's box" in Barker's novella The Hellbound Heart (1986), which he himself scripted and directed as the now classic horror film Hellraiser (1987). And like the Japanese puzzle boxes that have become Chinese, Barker's "little bastard" has a life and will of its own.

Since its release, Hellraiser has spawned a veritable industry of related films and comics, and a huge cult following that can't get enough the horrors that the box released. Various replicas of the Hellraiser Puzzle Box, some very intricate and expensive, are also for sale.

Pandora's "box"

In the Hellraiser story, Frank Cotton returns to England from a visit to an unnamed country with a mysterious Chinese puzzle box. He bought the box because it comes with a promise of stronger sexual sensations, which he can't wait to enjoy with his brother's wife, with whom he is having an affair. When he opens the box, he is sucked into the world of the Cenobites, who take him to the limits of unbearable pleasure and pain. He is able to return to his world, but can survive only on the blood of other people.

This is a variation of the Greek myth of Pandora, which itself has numerous versions. As told by Hesoid (circa 700 BC) in Works and Days, Zeus gives the beautiful Pandora to the titan Epimetheus with a storage jar as a dowry. Epimetheus, who has been told not to trust any gifts from the gods, falls in love with Pandora but tells her she was never to open the jar. She does, though, and before she can replace the lid, just in time to keep hope in the jar, she releases all possible misfortunes on humanity.

Pandora -- whose name means that her personal traits were gifts from the entire pantheon of gods -- had cousins like Eve, who brought the same miseries to Adam's world by partaking of a forbidden fruit. All beautiful seductresses trace their ancestry back to such early femmes fatales.

European paintings of Pandora show a box, rather than a jar, apparently because Erasmus of Rotterdam (c1466-1536) mistranslated the "pithos" in Hesoid's story, or confused it with the box Aphrodite gave Psyche with orders not to open it, in The Golden Ass, a much later story by Lucius Apuleius (c123/5-c180 AD). Psyche, also unable to control her curiosity, opened the box and found not beauty but sleep.

So the bastardization of "Japanese" into "Chinese" puzzle boxes -- and a Chinese puzzle box into a portal to evil like the Lemarchand's box in Barker's tale -- is par for the course in the history of cultural migration, adoption, and adaptation mal and otherwise.

PlayMarian Bower and Leon M. Lion NovelMarian Bower and Leon M. Lion MovieThe Chinese Puzzle The Chinese Puzzle was performed as a play in 1918, published as a novel in 1919, and released as a movie in 1932. The writer and actor Leon M. Lion (1878-1947) played Marquis Chi Lung in both the stage and film versions. Lion also played Old China handsIn the novel, Roger de la Haye decided to follow in the footsteps of Sir Aurthur, his father, who had devoted his life to British relations with China. Roger himself had spent most of his life in China, and his upbringing had been strongly influenced by Chi Lung, a mandarin who became a close friend of his father's when Sir Arthur had helped prevent Chi Lung's family land and tombs from being seized and destroyed by the court. Back in England for a visit with his mother, Amabelle, Roger meets Naomi, who strikes his fancy. Amabelle learns that though Naomi's family was not rich, "the girl's father had been in the consular service in the East" (page 33), and he and Sir Arthur had known each other when they were young men (page 37). The Chinese RoomRoger invites Naomi to the family home at Zouche de la Zouche. Amabelle has planned a small party in the "Chinese Room" -- Sir Arthur's large study -- which had not been used since his death five years ago. She has not yet told Roger, though, and tension builds when Naomi turns a conversation with Amabelle and Roger to the room, which Roger had described to her (pages 48-49).

The secret drawerAmabelle tells Roger the room is now unlocked and urges him to show it to Naomi. She opens the double doors and lingers in the salon outside when Roger and Naomi enter the room and the doors swing all but closed behind them (pages 51-52)

Chapter 4 thus lays the foundation for the intrigue that unfolds in the rest of the story. Suffice it to say that the "Chinese puzzle" does not involve a box, or boxes inside boxes. Note on Leon M. LionLeon M. Lion was known for playing yellowface on stage and screen. He played The Mandarin in another Guy Newall celluloid thriller, Chin Chin Chinaman (1931), which was released in the United States as The Boat from Shanghai. Hal Erickson describes the plot of the film, and comments, as follows (The New York Times, AOL).

|

Captain W.E. Johns Captain W.E. Johns Captain W.E. Johns -- William Earl Johns (1893-1968) in real life -- wrote nearly 200 books, half of which featured the adventures of the British ace James Bigglesworth. Most of the stories, written for readers in their teens, taut and packed with suspenseful action. "Biggles" to his friends and foes is an active then deactivated RFC (Royal Flying Corps) and RAF (Royal Air Force) ace who finds someone in every sky, jungle, and desert in the world who needs the services of a man who was born with wings and courage. Wherever Biggles has been, there are many serious collectors and fans. The International Biggles Association (IBA), based in The Netherlands, hosts auctions of his used books, and sells new reprints, audio books, comics, news magazines, stickers, lanyards, book plates, and DVDs, in addition to providing information about the hero. W.E. JohnsBiggles is clearly an imaginary projection of W.E. Johns' own military career (IBA website).

BigglesAs is fitting of any hero, Biggles also has a proper biography (IBA).

Biggles continues to work for the Secret Intelligence Services. He pursues assignments all over the world with Algy and new team member Ginger Hebblethwaite. During World War II, he becomes the leader of a Spitfire squadron, and Lord Bertie Lissie and other pilots join Biggles in one adventure after another. Biggles in the OrientBiggles in the Orient and Biggles' Chinese Puzzle are but two of many Biggles' adventures set somewhere in Asia. Biggles in the Orient was published in late 1944, when British forces were deployed mainly in India to contain Japanese in Burma, and to help supply Chungking (Chongqing), the wartime capital of the Republic of China, by air. The story is set earlier in the war, when lifelines to China had not yet been fully secured. An air service has been established "up the Himalayas to Tibet, and across the Tibetan plateau to China" (page 18), to avoid Japanese interference from the northern extremities of Burma. Many planes are disappearing, though, despite reports from pilots who have gotten through that the route is clear. Biggles' mission is to find out why. Biggles' Chinese PuzzlePublished in 1955, one year after the defeat of French forces at Dien Bien Phu in Vietnam, Biggles' Chinese Puzzle reflects the title of the first of eight short story in the book. "Biggles' Chinese Puzzle" (pages 7-57) finds Biggles in Saigon to determine who is profiting from difference in the exchange rates in Vietnam and France. The US dollar is 40 piastres, or 680 francs, in Saigon. The dollar in Paris is worth 400 francs. Simple arithmetic. You make 280 francs for every dollar you buy in France and sell in Saigon. After explaining the math, Biggles says there's a problem, and Ginger knows what it is (page 9).

How the culprits are doing this is the "Chinese puzzle" that Biggles and his mates must solve in 51 pages. The only boxes in the story are the antiquated "crates" that ex fighter pilots are ferrying around Indo-China. At the Pagoda Palace, Biggles meets Bollard, an American vet who works as a delivery pilot under an American aid plan (page 18). His flight to Saigon from Cairo, by way of Baghdad, Karachi, Calcutta, and Bangkok, is eased by diplomatic passes that cut through the red tape (page 20). Biggles' "Chinese" puzzleBoth men are staying at the Pagoda Palace. Bollard wonders how Biggles finds the place (page 21)

The rest of the story is predictable -- but I have to admit, it was goldarned fun getting there -- and I didn't have to look too many words up in the dictionary. Military scienceThe paperback edition I have cited conveys the following message to the reader on the page facing the first page of "Biggles' Chinese Puzzle" (page 6).

1967, when the paperback edition was published, marked the first of the three worst years in the advancement of American military science in Vietnam. |

Katherine Wigmore Eyre Hardcover editionsNew York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, April 1959 London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1960 Newspaper editionStar Weekly Complete Novel Paperback editionsNew York: Permabooks, 1960 (M4167) New York: Popular Library, nd (60-2144) Katherine Wigmore Eyre (1901-1970) was a "third generation San Franciscan" according a profile in the Popular Library edition, and The Chinese Box, set in the 1880s, became a minor bestseller in the city. A later novel, The Sandalwood Fan (1968), also involves things Chinese in San Francisco. The Spencer familyLilas Spencer lives in the Spencer family mansion on Nob Hill. The grounds are kept free of leaves by a Chinese gardener with a bamboo broom. Servants include a Chinese houseboy named Lew, old Sang in the kitchen, the Irish parlormaid waitress Norah, Nellie the upstairs maid, and buggy driver Wrenn. The mansion is the home of Edith Spencer, who had inherited Spencer and Company, a shipping firm, from her father. Living with her were two younger cousins, Gregory and Lilas, who were also husband and wife. Gregory had become the head of Edith's household and company. Lilas and Gregory, distant cousins, were four and eight when their parents were killed in the same Italian train accident. Edith, an older cousin who had never married, who the children had learned to call Aunty, took them in and raised them. Even after they married, though, they continued to live in the Nob Hill mansion, as Edith was getting senile and relied on Gregory, "a rock of dependability, a rock of trust and loyalty and devotion" (Popular Library edition, page 7). Randall returnsFrom her bedroom window, Lilas cannot quite see the wooden wharves along the Embarcadero, but she knows the Star of China is berthed there, and that Randall is back from Canton. The shunned "rolling stone" of the family, he had been sent away in disgrace eight years ago, but he had come back on the ship tied up at Pier 10 at the Battery and Front wharves. Randall was another cousin who, when Lilas and Gregory were young, had suddenly come to live with them. His hair was as black as theirs, but he was always getting into trouble and otherwise destroying the "serenity" of the Spencer palace, in which Edith was queen, Lilas was a princess, and Gregory was a prince who would someday be king. Now Randall was back -- dark-skinned, almost swarthy. Not just back, but successfully back, for he was now Captain Spencer Randall, not only the commander but also the owner of the Star -- a ship the Spencer and Company had once owned, but which Gregory had sold. She had been a coastal tramp when Randall later found her, picked her up, overhauled her, and put her back on a money-making run that had brought, in fifty-eight days, a cargo of silk, tea, hemp, porcelain, and himself from the Orient to San Francisco. The ivory boxRandall has also brought Lilas a belated wedding present. She does not want it but "couldn't not" accept it and open it in front of everyone. In the stiff gold paper was an ivory box -- not just one box, but boxes within boxes. When Randall leaves, she puts the box on her dressing table, and she and Gregory change into their night clothes. He calls her to bed but she goes to the window. She can just make out the docks at the end of the cobbled streets that run to the bay, and is imagining the lights of the Star when Gregory speaks (page 18).

The blurb on the cover of the Popular Library edition calls this "The chilling novel of a girl fleeing a demonic lover -- and a strange Oriental box that holds the clue to her fate." |

Robert Martin This is one of several volumes in an easy-reading series for children. Giner Pennylove is a carpenter who laughs a lot, and her life involves lots of action and fun with other characters that have real family backgrounds. To be continued. |

John Creasey The British writer John Creasey (1908-1973) is supposed to have published "562 full-length books under 28 pseudonyms" in 40 years according to one biographer. That's nearly 1.2 books a month, according to my Casio. Best known for characters like Scotland Yard officer Gideon, and the jewel-thief-turned-antique-dealer-cum-amateur-sleuth John "The Baron" Mannering, Creasey also wrote romantic fiction as Margaret Cole Creasey, and westerns as Ken Ranger, William K. Reilly, and Tex Riley. Writing as Anthony Morton, Creasey created the very likable John "The Baron" Mannering, a reformed jewel thief who became an antique dealer, amateur sleuth, and gentleman. The first Baron novel came out in 1937 as Meet the Baron in Britain and The Man in the Blue Mask in the United States. Murder in the boxesThe cover blurbs are perfectly pitched to invite reading without giving much away.

UndercoverMannering has been invited to Hong Kong by antique dealer Raymond Li Chen, with whom he has done some business, to see a collection of antiques. He decides to go by ship and fly back. Make a vacation of it. Aden, Karachi, Colombo, Singapore, Hong Kong (page 15). Mannering then gets a call from Superintendent William Bristow of New Scotland Yard, and by the time they have finished dinner, he has agreed to find out what he can about a huge operation in smuggling old ivory and jade carvings out of China. Mannering secretly relishes the prospect of having more to do in Hong Kong than see an exhibition. He worries only about how to tell Lorna, his wife, who has looked forward to a genuine break from his usual routine (page 21). As the blurb has forewarned us, by the time Mannering reaches Hong Kong -- not by sea but by air, and alone, his wife safely left with friends at the British Embassy in Bangkok -- he is up to his chin in intrigue, with a passport identifying him as James C. Mason, who has told the stewardess that he has never been there (page 80). The cover blurb not withstanding, there are not boxes in the story -- and no "Chinese puzzle" other than the one Manning must solve as a "highly respected consultant" for Scotland Yard. Note on The Baron seriesA total of 47 Baron titles were published between 1937 and 1979, the last two or three posthumously. Some 38 of the titles had been published by autumn in 1966 when "The Baron" series began to air on television. Some 30 episodes were broadcast between September that year and April the next. Number 11, which aired on 7 December 1966, was called "Samurai West" and had this plot, according to www.tv.com.

"The Baron", which starred Steve Forrest as John Mannering, appears to have been first broadcast in the US (www.tv.com).

|

Gerald Chan Sieg An immigrant Chinese family in Georgia sends for a box of Chinese presents for family and friends every year. The things in the box evoke all sorts of memories and good will. To be continued. |

Marjorie McEvoy Phoenix Press, which brought out many mysteries and westerns in the 1930s and 1940s, was absorbed by Arcadia House, one of its arch rivals, in 1952. In the 1960s, Arcadia was sold and became Lenox Hill Press, which "has never published a regular mystery line and abandoned its long-standing series of Westerns in 1975" (Bill Pronzini, "The Saga of the Risen Phoenix", in Bill Pronzini, Gun in Cheek: A Study of "Alternative" Crime Fiction, by Bill Pronzini, New York: Coward, McCann & Geoghegan, 1982; web version viewed 10 August 2006). Hong Kong GothicLenox Hill did, however, publish writers like Marjorie McEvoy, a fairly prolific British author of mostly romance and Gothic fiction set wherever whim takes her -- Hong Kong in the case of The Chinese Box (1973). The front flap of the dust jacket tries to hook the reader with this bait.

The jacket also explains that McEvoy won a prize trip to Japan in 1969 that took her to Tokyo, Hong Kong and Bangkok, where she took "copious notes for future reference". Her "love of far places" like these "comes naturally" to her because she is the "great-granddaughter of a captain on one of the China Seas clippers". Queer-sounding name, EurasianSarah Bourne and her friend Delia, both nurses, had gone to the Hong Kong area to help after a typhoon. Sarah had worked in Macao and Delia in Kowloon. Delia met Lee Shen, who worked in a curio shop, and he accompanied her to Britain when she learned that her grandfather, Mr. Stanton, who planned to leave her his antique shop, was dying. They were not in time. Delia and Shen were hastily married, but it is not clear when. First Sarah says "they married in indecent haste as soon as old Mr. Stanton died" (page 13). Later she says "There had apparently been a hasty wedding" (page 16) before they left for England upon hearing that Mr. Stanton was dying. Sarah, back in England, had not heard from Delia for some time, so decides to visit Delia at the antique shop, but finds it empty. Mrs. Clements, who ran the wool shop next door, had known Mr. Stanton well, knew he was fond of his granddaughter, and had been surprised when Delia "turned up with such a queer-sounding name, married to a Eurasian" (page 15). Baffling as a Chinese puzzleSarah is surprised to hear from Mrs. Clements that Delia had been in a car accident that left her almost blind, which explained why she had stopped writing to Sarah. Mrs. Clements also tells Sarah that Lee Shen had taken Delia back to Hong Kong, saying he knew a specialist there (page 17).

Before leaving, Lee Shen had packed the best stock in the antique shop for shipment to Hong Kong and sold the rest. One day Delia had entrusted Mrs. Clements with "a lovely little red lacquer trinket box" to give to "Sally" as Delia called Sarah, should Sarah ever come by. Later, Lee Shen had barged into the wool shop, demanding it back, saying it was valuable, Delia had no right to give it away, and he would bring the police. Mrs. Clements says the box "had a number of little compartments for jewels, and almost certainly a secret compartment containing Delia's message" (page 21), for Delia had said there was an "urgent message hidden inside" for Sarah, but Mrs. Clements hadn't seen it when she looked. The imperious hunkSarah Bourne takes the first nursing job she can find in Hong Kong, with deeply tanned and madly handsome Doctor Marcus Loughton. While helping Marcus with his private practice, Sarah will also help his wife, Julia, who polio has left in a wheelchair with an untreatable paralysis (page 27).

At Kai Tak airport, Marcus "imperiously" calls to a smiling Chinese, his chauffeur, Chan Lai, and says "He's a good chap and considers himself almost one of the family." Above the door of the Loughton house are the words "Ho Lan" (page 32).

The door was opened by "a wizened little Chinese woman" with a replica of Julia beside her. The girl rushes to her father, who says to the woman, "Has she been good, Amah?" And the amah says, "Velly good, master." Lili -- slit cheongsam 1Enter Lili, Julia's personal maid (page 35).

Sarah was convinced that "her interest in the doctor went deeper" when she cast the doctor "her inscrutable glance" as he left the room. The Loughtons also have a cook, and a "boy" Ah Wong who waits their table, and has "curious black eyes" (pages 37, 54) Sarah could not trust. On the trail of Lee ShenSarah asks Marcus if he knows a curio dealer named Lee Shen. He doesn't, but if she is buy any curios, she must let Chan Lai do the bargaining with the dealers because "He knows them better than you do" (page 50). Chan Lai cannot find an a curio dealer named Lee Shen in Hong Kong, but an uncle with a tailor shop in Mongkok, in Kowloon, has told him there is such a dealer in "an obscure alley named Ho Wan" (page 50).

Sarah goes in search of Ho Wan alley. She is addressed as "missee" whenever she asks directions (page 57).

After franticly breaking away from a dirtily dressed Chinese man -- "His slant eyes looked her over; then his hand closed over her arm as, grinning, he muttered something in Chinese" (page 59) -- she finds Lee Shen's shop and, in it, Lee Shen (page 62).

Soon she spots the Chinese box. She admires it and Lee Shen says, "Madam has perception" (page 64). She continues to show interest in it, but when she wonders how expensive it is, he tells her it is for decoration only and not for sale. Can he interest her in another box? No, but she will take a lovely pink Chinese fan at a bargain price. As he bows her out into the now deserted narrow alley, she thanks him and promises to return (pages 67-68). Suzy Kung -- slit cheongsam 2I would end on this note of unbearable suspense, but one more wrinkle in the plot deserves mention. Julia has spoken to Sarah of Suzy Kung, a pharmaceutical company rep through which her husband buys most of his drugs and dressings (page 71).

And six pages we see her through Sarah's eyes (page 77).

It is not clear who is more distracted by the slits in Lili's and Suzy's cheongsams -- Marcus, Julia, or Sarah, or the author who created them, or this reviewer. |

Christopher New Christopher New, who founded the Department of Philosopher at Hong Kong University and taught there many years before moving to Malta to write full-time, is best known for Goodbye Chairman Mao (1979) and Shanghai (1985). His first novel, The Chinese Box (1975), did not gain attention until later, and if not his best is doubtlessly his shortest and bitter-sweetest. China Coast TrilogyBoth The Chinese Box and Shanghai, with A Change of Flag (1990), are now called the China Coast Triology, in the manner of Anthony Burgess's The Malayan Trilogy (1964, also published as The Long Day Wanes: A Malayan Triology -- Time for a Tiger, The Enemy in the Blanket, and Beds in the East -- set in Malay during its struggle for independence after World War II), and Paul Scott's much better known The Raj Quartet (1966-1975 -- The Jewel in the Crown, The Day of the Scorpion, The Towers of Silence, A Division of the Spoils -- set in India from 1942-1947, the final years of British rule during and after World War II).

These three novels were not originally conceived as a trilogy. The Chinese Box, though published a decade before Shanghai, is set more than a decade later and is not part of the Denton saga. Lumping The Chinese Box together with Shanghai and A Change of Flag, and calling them a trilogy, is a cheap marketing gimmick that will disappoint readers who buy it thinking it might also be about the Dentons. Pessimistic teaserThe front fly of the Asia 2000 edition conditions the reader's mind with this gloomy preview.

Transparent plotNew gives away the plot from the very beginning. The book opens with Dimitri getting out of bed, having just had sex with Julie, a bar girl he's been seeing. The scene runs four pages, and from it we know all we really need to know about Dimitri's character. Julie soon loses her status as his lover but does not disappear from his horizon. New has troubled to give Julie a name, kept her in both Dimitri's thoughts (page 39, where he compares her laugh with Mila's) and in his vision (pages 50-51, where he runs into her on a beach with a sailor leaving the next day for Vietnam), and even insinuated that he likes her (page 56, where he tells Mila, who has asked if he thinks she is a whore, "If you were, you wouldn't be the first I've known. And liked." Julie contiues to pop up here and there, only to remind the reader that she is still in town, and in Dimitri's thoughts. So who could be surprised when, at the end of the story, having lost both Helen and Mila, Dimitri returns to the bar where she had been working, and finds her gone. It takes only the last half of the final page for the same mamasan to persuade Dimitri to hook up with Cherie, who claims she's twenty-one, and whose hand in his is "very small, smaller than Mila's or Julie's" (page 158). Mitigating factorsThe blurb on the back informs the browser that Bradley Winterton, of the South China Morning Post, said of The Chinese Box that "Hong Kong should be eternally in New's debt . . it has a genuine masterpiece to its credit. I bought the book, but I don't buy the hype. By what stretch of the paleocolonialist imagination can the Fragant Harbor possibly be indebted to a novel that views it through the eyes of an aging foreign devil, who relieves his loneliness by reading the palms of ever younger Chinese whores? In Cantonese no less? Come to think of it, though, it's his home. |

||||||||||||||

Marele Day In an English world dominated by British and American fiction, people never hear that places like Canada and Australia also have Chinatowns. Dan Mahoney's The Two Chinatowns (2001) sets a lot of action in the smaller Chinatowns of New York and Toronto, before Cantonese-speaking Detective Cisco Sanchez, NYPD's finest, has to go to Hong Kong, the world's biggest Chinatown, to nail his 14K nemesis. Sydney's ChinatownClaudia Valentine is Sydney's finest private eye, albeit she lives in one of the city's more rundown neighborhoods. Her creator, Marele Day, employed her four times from 1988 to 1994. Her second assignment, in The Case of the Chinese Boxes (1990), is described on the back cover like this.

The mysterious Mr ChenValentine has let herself into a a flat where she is to meet "the mysterious Mr Chen" (page 2). She is not sure the name is really his, she tells us in first person, and adds: "It sounded like the Chinese equivalent of Smith or Jones" (page 2). While waiting, she flips through a "stack of magazines -- Far Eastern Economic Review, Asiaweek, South China Morning Post" (page 2). All were, at the time Day wrote the novel, Hong Kong periodicals. The Review and Asiaweek folded after American companies bought them and destroyed them. The Post, not a magazine but a newspaper, is still thriving after the 1997 change of flags. Chen finally arrives with a somewhat older woman who like him. He does the talking, she sits and listens. Chen's family had business interests in Chinatown, he says. As Valentine knows, there had been a bank robbery a few weeks ago. Some safety depost boxes were stolen. One of them belonged to his family. In it was a precious key, worth nothing in terms of money but of great value sentimentally. Eye to eyeChen shows Valentine a photo of the key. He wants her to find it. Why her? she asks him. The older woman answers (page 4).

When the woman takes the photo back, Valentine asks her what the key is to. It's not to anything, she says. It's just a family heirloom. Chen's name is Charles, and the woman, Mrs Victoria Chen, is both the propritor of The Red Dragon restaurant, and his mother. Chinese keywordsNot until we are two-thirds into the story does Valentine decide it is about time to find out something about Chinese keys. She stumbles into an old library and probes its computer catalog (page 119).

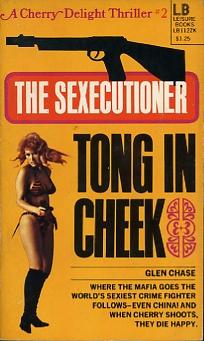

Chinese folkloreThere was nothing under 'boxes' either, but 'power of keys' led her to Matthew xvi, 19, in which Jesus said to Peter, "'I will give unto thee the keys of the kingdom of heaven'" (page 120). Valentine wonders if the key was what gave the Chen family its influence. At which point she looked for "instances of keys in Chinese folklore" -- and learn that "'A key is always given to an only son to lock him into life'" (page 120). She goes to the serials section and sifts through back issues of China Reconstructs. The November 1987 issue (we are practically in real time here) had photos of "Buddha boxes" -- but not all sides of boxes were shown -- a pity because one detail of interest to her was missing. Tong in CheekOf the three books she takes from the stacks, she saves Tong in Cheek till last (page 123, purple passages restored from original blurb).

Marele Day is not making this up. The blurb she cites is the actual blub on the fly of a novel published in 1973, called Tong in Cheek, which is Number 2 in Glen Chase's Cherry Delight Thriller series. Tellingly, Day omits the very parts of the blurb that suggest what moved Valentine to declare the novel, a patently pornographic thriller, unfit for a library. Thin plotThe Cherry Delight anecdote may raise a chuckle or two, even from readers who think Day made it up. The fun, though, comes at the expense of a plot that, in the final third of the story, turns lumpy rather than thick -- like a gravy that began with the right ingredients but wasn't properly stirred. A note on Cherry DelightWhether Cherry Delight belongs in the same stacks with Claudia Valentine, the N.Y.M.P.H.O. agent has seen a lot more action. Glen Chase, her creator, was the pseudonym of Gardner Francis Fox (1911-1986), Rochelle Larking, and Leonard Levinson. Fox also wrote as Troy Conway -- another house name he shared with four other authors -- and Rod Gray, Simon Majors, and Bart Somers. The Glen Chase team cranked out 24 volumes in the Cherry Delight "Sexecutioner" series from 1972-1975. Five more titles in an "all new" series were published in 1977. The Troy Conway combo was responsible for 34 volumes in a series featuring Rod Damon, otherwise known as "Coxeman: The Man From O.R.G.Y". |

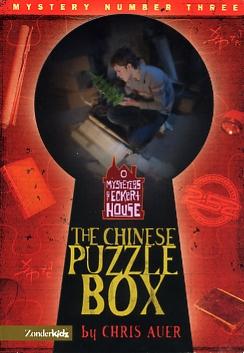

Chris Auer Zondervan was founded as a bookseller in 1931. It first published the New Testament of the New International Version (NIV) of the Holy Bible, in partnership with the International Bible Society, in 1973 and the complete NIV Bible in 1978. NIV overtook the King James version as the number one Bible translation in 1986. In 1988, Zondervan became a division of HarperCollins. So Zondervan now sells Bibles, books, and other Christian products all over the world as HarperCollins' evangelical imprint. 252 Soul GearThe Chinese Puzzle Box is published by Zonderkidz, which is Zondervan's children's group. It is part of the "252 Soul Gear series" based on Luke 2:52: "And Jesus grew in wisdom and stature and in favor with God and men" -- from NIV, of course. Luke 2:52 is said to be one of the few in the Bible that "provides a glimpse of Jesus as a boy." Readers are urged to become "smarter, stronger, deeper, and cooler" as they "develop into a young man of God with 2:52 Soul Gear" -- which Zondervan has trademarked, in case you were thinking of using it on your publications. The story begins to heat up on page 12, when 12-year-old Dan Pruitt recalls that his dad wanted him to think about a verse from the Gospel of Luke.

The storied pagodaThe plot starts to sizzle by the end of Chapter 2 -- which means we have already read one-fourth of the story. Miss Alma Louise Stockton LeMay, who is in charge of Eckert House, an old mansion, now a museum, full of secret passages and staircases and trap doors. Miss Alma invites Dan, his cousin Pete, and their best friend Shelby, into her office. There are roses on her desk, which the boys think are from her boyfriend (page 31).

The black-and-white illustration after this scene, at the end of chapter, shows a five-storied pagoda, like the one Dan is holding on the cover. Dan, though, is confused by something else (pages 33-34).

ABC and XYZThe pagoda was one of two puzzle boxes Julius Eckert had brought back with him from China in 1875. Sixty pages later, Dan is led to the second box, which is not a pagoda but an ABC. Rick, a bad boy who is also looking for the treasure, had already found the ABC but discovered that it takes two people to assemble it. So the boys agree to cooperate, and when all the parts are in the right place, a drawer pops open, in which they find the treasure, an XYZ, handwritten in Chinese. The boys struggle over the XYZ, which Rick thinks had been a gift from Kublai Khan to Marco Polo (1254-1324), who "had presented Kublai Khan (1215-1294) with a copy of the Holy Scriptures in Latin" (page 107). Dan is about to lose his life when an FBI agent comes to his rescue and arrests Rick. When the XYZ turns out to be from only the mid 19th century, and not the late 1200s, Dan decides that it was not very valuable, particularly back in 1875. Miss Alma, though, reminds him that it is, after all, an XYZ, which causes Dan to agree that it was in fact "a treasure of greatest worth" (page 120). |

English title -- The Chinese Box Director -- Wayne Wang Jeremy Irons -- John, British journalist, loves Vivian Wayne Wang's 1997 film The Chinese Box is both set and shot in Hong Kong on the eve of its reversion to China on 30 June 1997. The relationship between John (Jeremy Irons) and Vivian (Gong Li), however, pretty much follows the "Suzie Wong" pattern in that it represents the mysterious "Orient" that can't quite be comprehended by, in this case, a British journalist who considers Hong Kong his home and, though he knows he is dying with leukemia, continues to document the human condition in the city through his camcorder. The movie is based on a story written by Jean-Claude Carriere, Paul Theroux, and Wayne Wang. It is not an adaptation, as some people seem to think, of Christopher New's 1975 novel by the same name, which was also set in Hong Kong but during the Cultural Revolution in the late 1960s. Wayne WangWayne Wang was born in Hong Kong in 1949 as Wang Ying, and his father also named him after his favorite actor, John Wayne. Wang came to the US at age 17 and studied film and television in Oakland, California. He returned for a while to Hong Kong then settled in San Francisco. Both of Wang's earliest major films, Chan Is Missing (1982) and Dim Sum: A Little Bit of Heart (1985), are set in San Francisco's Chinatown. Eat A Bowl Of Tea (1989), The Joy Luck Club (1993), Smoke (1995), and Blue in the Face (1995) are among other notable films Wang made before Chinese Box. More recently he has directed Anywhere But Here (1999), The Center of the World (2001), and Maid in Manhattan (2002). Runaway identity crisesIn The Chinese Box, Wang seems to have gotten carried away with identity crises. Every character in the movie, even Hong Kong, arguably the main protagonist, has one. Wang was probably looking back at Hong Kong with the sort of mixed feelings that all people who change their childhood homes inevitably embrace. To be continued. Jean-Claude Carriere (screenwriter, screen story) Forthcoming. |