An American salt in the Philippines

Bearing crosses and breaking conventions

By William Wetherall

First posted 1 September 2006

Last updated 1 September 2006

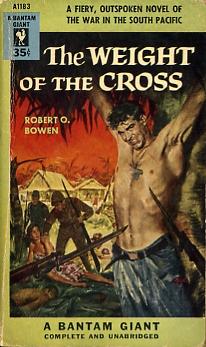

Robert O. Bowen, The Weight of the Cross, 1951

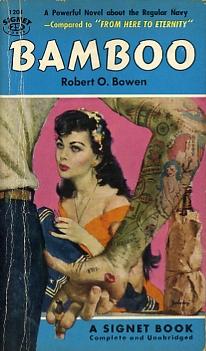

Robert O. Bowen, Bamboo, 1953

Robert O. Bowen

Robert O. Bowen (1920) joined the U.S. Navy whe he was seventeen, according to a blurb on the back of one of his novels. He served in the Caribbean and later with the Asiatic Fleet, first in the China Seas, and then in the Philippines, where he was captured and spent three years in a Japanese POW camp. Both The Weight of the Cross (1951) and Bamboo (1953) reflect his experiences in the Philippines.

Bowen was a professor of English literature at several universities and helped edit a number of journals, including Ramparts. His papers, covering 1948-1967, fill 18 boxes that occupy 9 feet at the University of Florida, where apparently he did not teach. Included among his manuscripts are a "Scene Cut from Weight of the Cross. Part used later in Bamboo."

Bowen's published a third novel, Sidestreet (Knopf, 1954), and a number of short stories, including those he collected in Marlow the Master and Other Stories (Colonial Press, 1963). He was also wrote poems and plays.

During the 1960s, Bowen's right-wing leanings and anti-communist activism inspired The Truth About Communism (Colonial Press, 1962). A teaching stint in Alaska resulted in An Alaskan Dictionary (Nooshnik Press, 1965), with definitions of local expressions like rocking chair money, rubber ice, halibut head, and greasy thumb.

Robert O. Bowen This novel tells the story of Tom Daley, a destroyer sailor who had "wrecked bars from Shanghai to Singapore" and was trying to "escape from the world and himself in the hot gin dives and shacks of Manila" when he was captured by Japanese at the outbreak of the Pacific War. The novel opens with Tom in a locked ward near Manila, where he is waiting to be discharged for insanity or to face a general court-martial. He had jumped over the side of the destroyer Thompson to swim ashore, and after being brought back in a whaleboat he had gone on a rampage and tried to kill the captain. The shooting begins and the facility has to be evacuated. Tom and Gaddy, who had cut a wrist and tried to hang himself when drunk, sneak away during the confusion and head for Bataan, via the Santa Ana barrio in Manila, where Tom knows a few people. Giddy asks, "What about the gooks?" Giddy worries. "You figure any of the gooks you know'll be at Santa Ana?" (page 56).

Tom had doubts about trusting Filipinos, no matter how much he liked them (page 57), but person he thought he could count on was Nigger Connie (pages 60-61).

Tom leads Gaddy to a gin mill called the Silver Dragon. Inside they find "Minook, the mestizo pimp, crouched between the end of the rough bar and the doors with a rusty bolo in his fist" (page 61). Tom persuades the reluctant Minook to take them to Bataan. Things don't go well. Tom at first puts Gaddy's suspicions about Minook at ease. When later he decides that he has to kill Minook with the bolo, Gaddy talks him out of it. (Pages 65-75) Minook runs off with the bolo and gunny sack of chow. Tom and Gaddy move on. Shortly they run into Minook -- and two Japanese soldiers with weapons leveled at all three of the men. (Pages 75-77) Tom appraises his captors, especially the one with the automatic who had said "Hands up" and thinks (page 78): I'm glad he's not like those weasely teeth-sucking slopeheads in Pekin. The Jap's face was tanned and heavy-boned like a North China coolie's, like a Mongolian's. He looked very hard but not mean. The officer assures Tom, in stiff English, that they would not shoot them. Tom notices that the automatic is a Colt .45 and "US" is stamped on the holster. Later Minook tells Tom he is not "mister big-shot" anymore and curses him out in Tagalog. The officer steps between the two men. Minook pleas for his freedom as a friend of Japones. Minook is also a friend of America, the officer says. Is he Tom's friend? he asks Tom, and Tom says "No." (Page 82) Minook is allowed to go, but when he is 50 feet down the road, the officer fires at him. A carbine also cracks. Minook falls. The soldier with the carbine puts more slugs into his body until his Navy jersey stops bucking. Tom suddenly feels sorry for Minook (page 83).

To be continued. |

Robert O. Bowen Bowen's declaration of narrative independenceIn a note at top of the first page of the story, Bowen declares his intention to break a "naturalistic" convention that limits the expressions a novelist can use to describe what is going on in a character's head.

To be continued. |