|

|

1947 Morrow hardcover

|

|

|

|

1950 Heinemann hardcover

|

|

|

|

1959 Heinemann hardcover

|

|

|

|

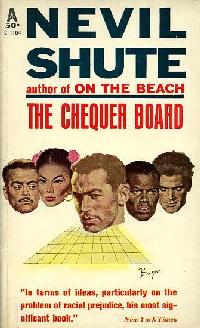

1961 Avon paperback

|

|

|

|

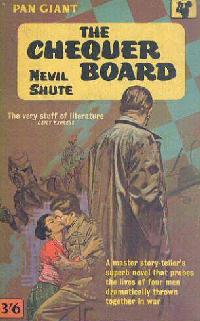

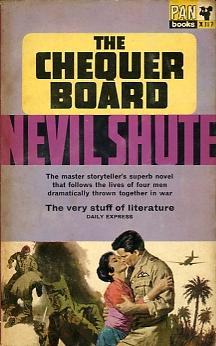

1961 Pan paperback

|

|

|

|

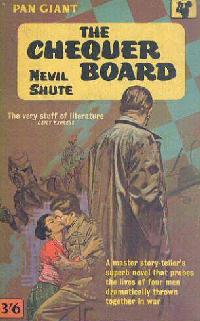

1963 Pan paperback

|

|

|

|

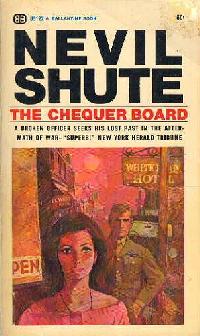

1968 Ballantine paperback

|

|

Nevil Shute

The Chequer Board

Hardcover editions

London: William Heinemann, 1947

316 pages, hardcover

New York: William Morrow, 1947

380 pages, hardcover

Paperback editions

London: Pan Books, 1962

264 pages, paperback (X117)

New York: Avon Books, 1961

paperback (G1104)

Toronto: Ballantine, 1968

paperback (U5122)

Thrown together in war

Wars, in their wakes, leave destruction and renewal, sorrow and joy, and actual and fictional accounts of survival. Nevil Shute was one of many productive writers that turned his own and others' war experiences into stories of how people came through the Second World War and pursued new lives unlike anything for foresaw before the war.

As the cover of 1963 Pan Books paperback edition states, The Chequer Board "follows the lives of four men dramatically thrown together in war". The back cover tells us who these four men are.

A COMMANDO who had killed the way he had been taught to kill . . .

A NEGRO accused of attempted rape . . .

A YOUNG PILOT -- the third husband of a beautiful wife, who already had a fourth in mind . . .

AN ARMY CAPTAIN with one foot in the Black Market . . .

"One violent moment in war had brought these men together", the blurb also states.

Four men in a guarded ward

The story is told by a neurosurgeon who, a few years after World War II, has examined John Turner and told him he has only one year to live as a result of head injuries he suffered in 1943.

Turner had been a captain in the Royal Army Service Corps. He and three or four other men, who were going to be court martialed, were en route back to the UK from Algiers via Gibraltar when their plane, with a crew of three, is attacked.

The attack leaves Turner wounded and unconsciousness. He wakes up in a hospital in Penzance, where the plane had belly landed in a field. There were three men in the ward -- Turner, another prisoner, the copilot who had landed the plane, and "an American Negro soldier" (page 16, Pan edition).

Turner and two other prisoners on the plane had been detained for selling Army supplies on the black market in London. Their racket had been discovered after they had been sent to the Mediterranean. The other two men, though, had died.

The only other prisoner who had survived the attack and crash was a paratrooper wanted for a murder in a London pub.

The Negro had not been on the flight. He had been stationed in Penzance and had fled when charged with trying to rape a local woman. American military police had chased him into an air-raid shelter, where he cut his throat.

"I got to find a nigger"

By the end of Chapter 2, Turner has declared to his wife that "I got to try and find a nigger" (page 31). This sets up the rest of the story -- Turner's quest for the other three men (pages 31-35, some parts omitted).

She turned to him in astonishment. "For the Lord's sake," she exclaimed, "what do you want with a nigger?"

"You remember that time I got in prison?"

"I do.

"I dunno if I ever told you much about that time," he said. "There was four of us all in the ward together, at that place down in Penzance. Just the the four of us together. They had a guard, you see."

"I remember."

"I'd like to know what happened to them other chaps, the three of them," he said. "They used to come and talk to me. Hours on end, they did."

"Talk to you?"

They used to come and sit inside the screen there was all round my bed, and talk to me. Hour after hour, sometimes."

What did they do that for?"

The doctor 'n the sisters made them do it." He turned to her. "I had me eyes all bandaged up after the operation 'cause they didn't want me to see anything, and they gave me things to stop me wanting to move about in bed. I was lying there all strapped up like a mummy, and I couldn't talk much, either. But I could hear things going on, 'n think about things too. Funny, being like that, it was. So as the others got well one by one the sisters made them come 'n read a book to me, but they read pretty bad, so most times they just talked. I could answer them a little, but not much. They just kept talking to me."

"What did they talk about?"

"Themselves, mostly. They were a bloody miserable lot -- the miserablest lot of men I ever saw. But they were good to me." He paused for a moment, and repeated very quietly: "Bloody good."

"How to you mean?" she asked.

"They were sort of kind. Do anything for me, they would. I reckon that I might have passed out that time, spite of all the doctors and the nurses, if it hadn't been for them chaps sitting with me, talking. God knows they had enough troubles of their own, but they got time for me in spite of everything."

There was a long thoughtful pause. Presently she said: "What's this got to do with a nigger?"

"One o' them was a nigger from America," he said. "the last one to go out. He was the only one I ever see clearly -- Dave Lesurier, his name was." He pronounced it like an English name. "Then there was Duggie Brent -- he was a corporal in the paratroops. And then there was the pilot of the aeroplane, the second pilot I should say -- Flying Officer Morgan. We was all in a mess one way or another, excepting him, and yet in some ways he was in a worse mess than the lot of us."

He turned to her. "I been thinking," he said quietly. "I never seen any of them from that day to this, though we was all in such a mess together that you'd have thought we might have kept up, somehow or another, just a Christmas card or something. But we never. Well, I got through all right 'n turned the corner. I got a nice house here, mostly paid for, and a good job. Folks looking at me would say I was successful, wouldn't they?"

She nodded slowly. "They would that, Jackie. We're not up at the top, but we're a long way from the bottom."

"Well, that's what I mean," he said. "A long way from the bottom. But that time I was talking of we was right down at the bottom, all four of us. Me and the other three. And when I was down there they was bloody nice to me. You just can't think."

"I see," she said.

"And I been thinking," he said quietly, "I been a bloody squirt not to have done something to find out about them other chaps, and see how they was getting on. They were bloody good to me, when I needed it."

He got up from his chair. "I'm just going in to spill some of this beer. Shall I bring out a rug when I come?"

It was the first time he had offered to do anything for her for a long time. She said: "Please. It's getting kind of chilly out here, but it's nice."

He went into the house, and came back presently, and handed her the rug. She wrapped it round her, and settled down to listen to him talking. They sat there on the lawn in the warm summer night, in the quiet grace of the moon, and the stars faint in the bright light. It was windless, still and silent. Around them, in the dormitory suburb, the world slept.

Shute has hooked his reader from page one, and now he has set the barbs. There is no putting the book down until its poignant end. Shute is that good a writer.

"Maybe next summer"

The story structurally focuses on Lesurier, who the narrator generally refers to as just "the Negro". The main part of the story begins with references to "a nigger" named Lesurier, who is more in Turner's thoughts than the other two men because he had been in the ward longer and was the only man Turner had actually seen.

It is structurally fitting, then, that Lesurier is the last man Turner locates, and the one to hope that he will see Turner again (page 266).

They said goodbye at the door. "Let's know when you're down in these parts again," the Negro said. "That likely to be soon?"

"Oh, aye," said Mr Turner. "I get down here once in a while. Next summer, maybe."

They got into the little car, and drove off to Penzance. At the wheel, Mollie said: "Why did you say we'd be down here again, Jackie?"

"Got to say something," he said heavily.

Telling what's already been shown

The penultimate scene ends with the following conversation between the Turners -- in which Shute takes off his novelist's cap and "tells" the reader what has already been more effectively "shown" (page 271).

Another time, he said: "I been thinking about these coloured people that I got to know about, Nay Htohn and Dave Lesurier. You know, there don't seem to be nothing different at all between us and them, only the colour of the skin. I thought somehow they'ld be different to that. They got some things we haven't got, too -- better manners, sometimes. I reckon we could learn a thing or two from them."

His wife said: "You got to remember that those two were different to the general run of coloured people, Jackie. They were educated ones."

"That's so," he said thoughtfully. "Maybe there's some sense in paying for all this schooling."

Implausibly seamless

The next and last scene very briefly passes the narrative baton back to the first-person voice of the neurosurgeon. The reader may very likely have forgotten the doctor, for the transition from his voice to that of a third-person narrator at the start of Chapter 2 was seamless -- though, upon reflection, implausible.

The doctor has not seen Turner for several months, and Turner shows every sign of not having long to go.

After Turner and Mollie have been seated, the doctor speaks the final words of the novel: "Well, Mr Turner, what have you been doing since I saw you last?"

I consider The Chequer Board the best of the three Shute novels reviewed on this site -- not withstanding the popularity of A Town Like Alice and Shute's own vote for Round the Bend.

|