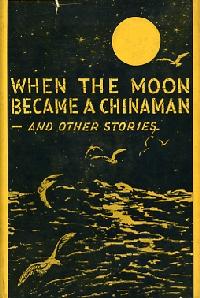

When the Moon Became a Chinaman

Soldiers of Christ and Uncle Sam fight the "yellow peril"

By William Wetherall

First posted 15 August 2006

Last updated 15 August 2006

Milton McGovern All I know about Milton McGovern is that, in 1924, he published a collection of short stories under the title of the leading story, "When the Moon Became a Chinaman" (pages 3-40). Or, more precisely, P.J. Kenedy and Sons, in the Catholic book trade since 1826, brought out his stories, all Christian inspirational tales with lots of Catholic twists and Irish Catholic humor. Gimp Gabrenya"When the Moon became a Chinaman" picks up speed when, one evening, a group of Catholics and a Pagan head for St. Jerome's church to hear a visiting preacher give a sermon on Foreign Missions. A fairly serious fifteen-year-old William "Gimp" Gabrenya, his father Mr. Gabrenya, and his aunt Maggie Cullen are joined by some equally wholesome but less-inhibited young Catholic friends, Bill Hennesy, Joe McFall, Sylvan McGarrigle, and Charlie Gillen -- and a Pagan lad the friends hope to convert, Joe "Floody" Flood, "who has never been inside of a church in his life, except once he slipped into a synagogue" (page 13).

No one knows anything about the preacher except what had been in the paper: Father Bonaventure O'Hara, O.F.M. is a Franciscan missionary who has been lecturing in America for a few months. Is he a Frenchman? Floody asks. No, from his name he's probably Castilian, Hennesy says. Then what does O.F.M. mean? Floody asks. Over for the money, McFall says. No, over for more, McGarrigle says. The Chinese laundrymanThey see "a young Chinese lad" who had stopped pushing his cart and was counting an assortment of bundles (pages 16-17).

In his sermon, the good friar tearfully pleas for more young missionaries to go overseas. Sure, there are plenty of people to convert in America, but charity does not stop at home. Keep most the priests and money at home, but "in the sweet name of Jesus Christ" give a reasonable amount of funds and a number of clergymen "to those millions of starving souls over there" (pages 22-23). God and countryThe preacher's final entreaty, though, is patriotic (pages 23-24).

The accidentBack on the street, everyone is walking in silence, absorbed in thoughts about the sermon, when they witness "a terrific collision between a seven-passenger automobile and a small cart pushed by a pedestrian" (page 25). Gimp is the first to arrive, and he pillows the head of one of the victims on his calves.

In the meantime, Father Robert Sullivan -- whose "spiritual assistance" had declined by another victim who told him "no more Romanism for me" -- turned to the man Gimp was supporting, and asked an automobile driver to direct his searchlight toward him (page 27).

The boy's eyes came open, looked into Gimp's face, "and his gaze seemed to linger there with a childlike expression of trust and love" (page 27). Divine graceFather Sullivan then tells the Chinese chap he will probably die, and asks him if he knows anything about Christianity. The boy's face lights up and he takes the priest's hand and holds it to his "tanned cheek" (page 28).

Gimp runs to a drug store, comes back with a coca-cola glass full of water, and thrusts it into Father Sullivan's hand (page 28).

"Oh, Jesus, Mary and Joseph, save him," Gimp whispers, when he realizes that the "poor wretch . . . now lay at death's door, powerless to retract his insulting words to God's minister, powerless to express sorrow for his past years of sinfulness . . . (page 29). Gimp was haunted by the eyes of the Chinese boy, and unable to forget the friar's words, he imagined himself in "far-off China" serving as a soldier of both Christ and Uncle Sam (page 31). Frator Edward, O.F.M.William Gabrenya was so moved he studied for the Franciscan priesthood and came to be known as Frator Edward, O.F.M. After his ordination, he disembarked for China with two elderly Franciscans who were returning to "their labors in the Orient" (page 37). On the deck of the ship one night, alone, Father Edward imagined the stars were "Oriental lanterns being hung out in the sky by the hands of little Chinese angels in heaven -- lights to guide him on his way to their earthly kinsmen whom they knew to be in so great need of him" (pages 38-39).

Now wasn't that a nice story, boys and girls? In 1924, the year this book was published, Congress passed laws that greatly limited immigration from Europe, and all but banned immigrants of Asian national origin. |