Agatha Christie

Niggers, Indians, and none

By William Wetherall

First posted 10 January 2006

Last updated 21 July 2024

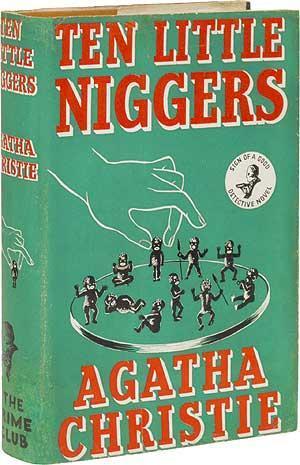

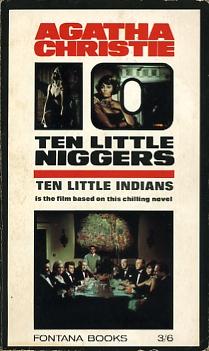

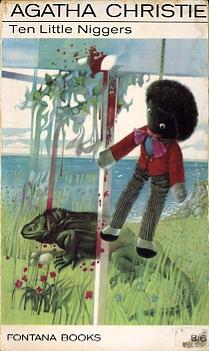

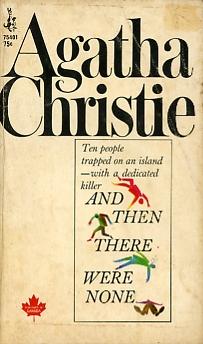

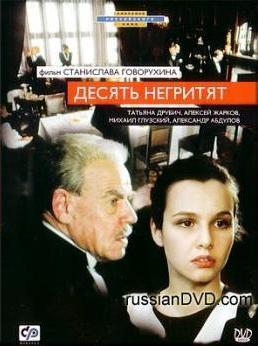

Ten little somethingsAgatha Christy, the working name of Mary Clarissa Miller Mallowan (1890-1976), also wrote as Agatha Christie Mallowan and Mary Westmacott. Her most famous and popular mystery, as published in the United Kingdom in 1939, was Ten Little Niggers. The stage adaptation first played with this title in London in 1943. The first American edition of the novel came out in 1940 as And Then There Were None. In the United States, the play has been called Ten Little Indians since its first Broadway production in 1944. The 1959 film (a TV version of the play) and the 1965 and 1989 films were also entitled Ten Little Indians. The first Pocket Books edition in 1944 was titled And Then There Was None. However, for several years from 1965, Pocket Books published the novel as Ten Little Indians -- at least in the United States. A 1968 Canadian edition of Pocket Books bears the title And Then There Were None. In the meantime, the novel continued to be published as Ten Little Niggers in the UK, as seen in the 1963-1967 Fontana paperback. Amazon.com markets Desyat' Negrityat, the 1987 Russian film directed by Stanislav Govorukhin, as "Ten Little Indians" -- showing, but not translating, the Russian title, which accurately renders Christie's original title. Released in the US as a DVD with English subtitles in 2002, the Russian film is regarded as the very best and most faithful of all movie adaptations of the novel. Publishing historyHere is a very sketchy and selective overview of the publishing history of the novel and the play, and their film versions, by title. Not all of the information has been confirmed. 1. Ten Little NiggersUK hardcover editions UK paperback editions UK productions of play Russian film adaptation 2. And Then There Were NoneUS hardcover editions US paperback editions Canadian paperback editions US film adaptations 3. Ten Little IndiansUS film versions US hardcover US paperback editions US productions of play and scenarios US flim adaptations The nursery rhymeThe name of the island on which the story unfolds is "Nigger Island" in "Niggers" editions, but "Indian Island" in both the "Indians" and "None" editions. The island is off the Devon coast, and the ten strangers who are lured there die, one by one, until there are none. Early in the story, one of the ten guests, Clara Claythorne, sees a poem on a big square of parchment in a gleaming chromium frame over the mantlepiece of the fireplace in her bedroom. She recognizes it as "the old nursery rhyme that she remembered from her childhood days." Here is how the poem appears in the "Indians" and "None" versions of Christie's novel. American version of Christie's poem Ten little Indian boys went out to dine; Nine little Indian boys sat up very late; Eight little Indian boys traveling in Devon; Seven little Indian boys chopping up sticks; Six little Indian boys playing with a hive; Five little Indian boys going in for law; Four little Indian boys going out to sea; Three little Indian boys walking in the zoo; Two little Indian boys sitting in the sun; One little Indian boy left all alone; This is the Americanized or "Indianized" version of the "Ten Little Niggers" poem in Christie's original novel. The "Niggers" poem was considered a nursery rhyme in Great Britain because it was popular with children. Christie wrote a number of novels around nursery rhymes, including One, Two, Buckle Your Shoe (1940), Five Little Pigs (1942), Three Blind Mice (1950), and Hickory Dickory Dock (1955). |

||||||||||||

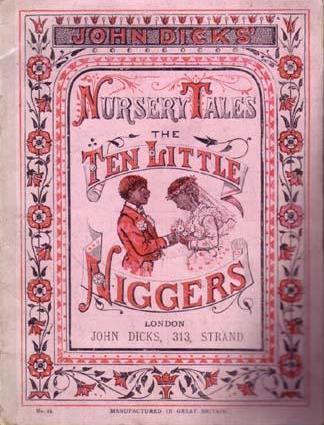

Happy endingsThe version of the poem in Christie's novel ends with all ten guests on the island dead. Eight have died, leaving Vera and Lombard. She clings to him and cries, "It's us now! We're next!" Vera then becomes convinced that Lombard killed the others and also plans to kill her. So she shoots him. Her relief doesn't last long, though. She tries to recall the last line of the poem. One little Indian boy left all alone. What was the last line again? Something about being married -- or was it something else? Her memory is then prompted by the sight of a rope hanging from the ceiling, with a noose at the end, and under it a chair. With "her eyes staring in front of her like a sleepwalker's" she proceeds to mount the chair, adjust the noose around her neck, and kick away the chair. In her own stage adaptation of the story, however, Christie allows Vera and Lombard to remain alive, fall in love, and get married. The marriage ending is actually represented on the cover of a children's book illustrated by John Dicks around 1880. The book is supposed to contain eight leaves, printed on one side only. Each leaf is said to have a color picture. It is not clear that the book contains the poem. The marriage version of the poem that appears in Christie's first novel reads like this. Ten Little Niggers Ten little nigger boys went out to dine; Nine little nigger boys sat up very late; Eight little nigger boys travelling in Devon; Seven little nigger boys chopping up sticks; Six little nigger boys playing with a hive; Five little nigger boys going in for law; Four little nigger boys going out to sea; Three little nigger boys walking in the Zoo; Two little nigger boys sitting in the sun; One little nigger boy living all alone; The above stanzas -- possibly with the hanging ending, a matter I have not yet been able to confirm -- were penned in 1869 by the British lyricist Frank Green for a Victorian minstrel show. However, Green's music hall song was an adaptation of the words of "Ten Little Indians", a comic ditty composed in the 1860s by the Philidelphia songwriter Septimus Winner (1827-1902) and published in London in 1868. Today Green would have had to get Winner's permission, and possibly pay him for the privilege of using his idea of "ten little somethings" becoming none. Ten Little Injuns Ten little Injuns standin' in a line, Nine little Injuns swingin' on a gate, One little, two little, three little, four little, five little Injun boys, Eight little Injuns gayest under heav'n, Seven little Injuns cutting up their tricks, Repeat Six little Injuns kickin' all alive, Five little Injuns on a cellar door, Repeat Four little Injuns up on the spree, Three little Injuns out in a canoe, Two little Injuns foolin' with a gun, One little Injuns livin' all alone, Observe that Winner's lyrics end on the happy note of marriage. Christie had second thoughts about the gloomy ending of Ten Little Niggers when adapting the novel into a play in 1943. The play ends more happily with marriage -- as did the original American ditty and, apparently, its British adaptation. |

Lost in "translation"

The most widely distributed version of Christie's novel represents an interesting distortion. The American original portrayed "Injuns" in American predicaments. In the British "translation" the "Injuns" they became "Niggers" in British predicaments. In the American "back translation" the "Niggers" became "Indians" but their predicaments remained British.

In other words, the standard version of the novel today, even in the United Kingdom, represents an American "Indianization" of what had been a British "Niggerization" of an American ditty about "Injuns". The story now hinges on a partially "re-Americanized" version of a radically "Anglocized" version of the original ditty. And one has to wonder what the ditty might have lost in its two trips across the Atlantic.

"Injuns" and "Indians"

"Injuns" remained a common vulgar expression for "Indians" in movies and fiction, and in the "Straight Arrow Injunuity Cards" that came in boxes of Nabisco Shredded Wheat in the late 1940s and early 1950s. But "Ten Little Indians" has become the standard title of the ditty in America. And the standard title of Christie's novel, on both Amazon.com (US) and Amazon.co.uk (UK), is now And Then There Were None.

What, though, do most British reads of Ten Little Indians or And Then There Were None make of the "Indians" on "Indian Island" off Devon? Without visual cues as to whether these "Indians" are "Native Americans" or "East Indians" -- they might well assume the ditty is about "East Indians" in Britain -- especially as

I would also guess that a British reader would be more likely than an American to understand what a "Chancery" was -- and imagine an "East Indian" as Chancellor in a court of equity. And that some American readers might wonder what ten "Indians" are doing in England.

Nigger in the woodshed

Editors of the American version substituted "Indian" for "Nigger" but let one instance of "nigger" stand.

In "Niggers" editions, Justice Wargrave grunted and thought to himself: Nigger Island, eh? There's a nigger in the woodshed.

In "Indians" and "None" editions, he grunts and thinks: Indian Island, eh? There's a nigger in the woodshed.

Do readers ever wonder what a "nigger" is doing in a "woodshed" on "Indian Island" off the shore of Devonshire?

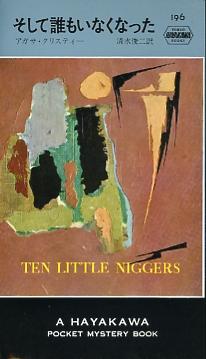

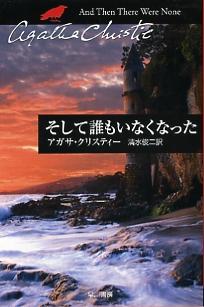

Japanese translation with different English titlesAgasa Kurisutii [Agatha Christie] Ten Little Niggers coverTokyo: Hayakawa Shobo, 1976 (1975) And Then There Were None coverTokyo: Hayakawa Shobo, 2005 (2003) Hayakawa Shobo, Japan's biggest publisher of mysteries in translation, brought out Shimizu Shunji's translation of And Then There Were None in its "Hayakawa Pocket Mystery Book" (HPB) series in 1975. Though the Japanese title and the content reflect the American version of the novel in which "Niggers" are replaced by "Indians", the cover shows the English title Ten Little Niggers. Hayakawa has changed the design and size of its pocketbook series a few times. Since the HBP 196 edition shown here, the English title has been And Then There Were None. |

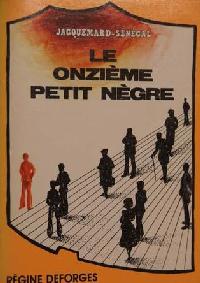

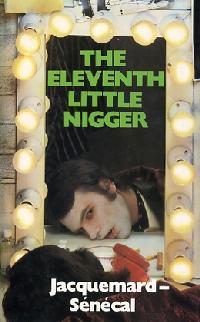

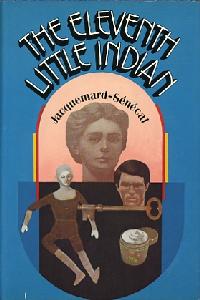

The Eleventh Little Nigger

|

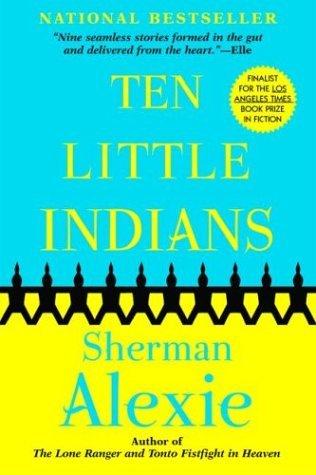

Sherman Alexie's anthologyTen Little Indians is the title of a number of other books -- most of them actually having to do with real "Indians" of the "Native American" variety. The hottest selling Ten Little Indians title today is Sherman Alexie's collection of short stories brought out by Grove/Atlantic in 2003. Alexie was born in 1966 on the Spokane Indian Reservation, in Wellpinit in the state of Washington, and is an extremely productive and versatile contemporary writer. His books include First Indian on the Moon (Brooklyn: Hanging Loose Press, 1993), a work of general fiction; Indian Killer (New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 1996), a murder mystery about a serial killer who scalps white men in Seattle; and The Lone Ranger and Tonto Fistfight in Heaven (Atlantic Monthly Press, 1993), a collection of short stories. He also wrote the script for the movie Smoke Signals (Hyperion, 1998). |

Then There Were NoneThen There Were None has also been pressed into service as the title of a book by Martha H. Noyes (Honolulu: Bess Press, 2003), a thin compilation of facts based on a TV documentary film by Elizabeth Kapu'uwailani Lindsey Buyers. The is said to presents a "visual journey of Hawai'i's places and people as seen through the lens of a painful history" and "offers an emotional awakening -- a potential oepn door for sharing, learning and healing." "Native Hawaiians" who want a sovereign voice is their affairs face a recognition problem. The term "Native American" as formally used by the Bureau of Indian Affairs does not include them, or other Pacific Islanders under US jurisdiction. Nor, strictly speaking, does it include "Native Alaskans" -- since "Indian country" does not extend beyond the 48 coterminous states. While someday Native Hawaiians might become so totally absored into the mainstream that they would no longer exist as a people, this is not likely to happen anytime soon. Politics if not demographics will probably ensure that there will never be none. Movements to gain Federal recognition of Native Hawaiians have failed. So unlike Native American nations they do not, under US laws, have race-based rights that come with sovereign tribal status. Under Hawaiian law, however, citizens with the proper quantum of Native Hawaiian blood receive special treatment in a number of state programs. And there are movements underfoot to enact a law that would enable the creation of a race-based voting registry of Native Hawaiians, as a first step toward some degree of political autonomy within the state. As of mid 2005, a bill called the Native Hawaiian Government Reorganization Act was before the US Senate. If passed into Federal Law, it will give Native Hawaiians a legal status like that of Native Americans under the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and native Alaskans. And apparently there are enough "Native Hawaiians" to matter in the polls, if they were to vote as a block -- which is highly unlikely. Some estimates put the number of Hawaiians of putatively Polynesian ancestry at about 250,000 -- out of a total of 1.2 million people in the 50th state. And there are as many as 400,000 "Native Hawaiians" in all 50 states. Native Hawaiians who favor total independence oppose the bill. They claim the law it seeks to enact would legalize their status as subservient Native Americans and otherwise keep them under the heel of the US government. They view themselves as an invaded and occupied people, and want nothing less that recognition as a separate nation. |