Japan in recent pulp fiction

Mishima clones, xenophobia, and morbid dreams

By William Wetherall

A version of this article appeared as

"Japan as seen in recent pulp fiction:

What's portrayed often has little to do with reality" in

The Japan Times, 25 March 1987, page 12 (Focus)

A much shorter version earlier appeared as

"Japan in Pulp (1): Bushido and Crime" in

Asahi Evening News, 4 December 1986, page 6

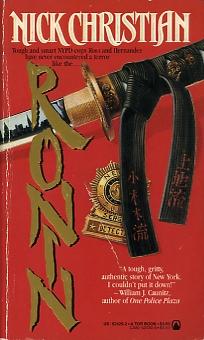

Nick Christian Three Japan potboilers with Shogunesque titles appeared in 1986. Ancient bushido is married to modern crime in both Nick Christian's Ronin and Marc Olden's Gaijin. Douglass Bailey's Shimabara continues the story of medieval Christian politics started by James Clavell's Shogun. Ronin is a martial arts farce. It is set in the United States and is cast with the kind of ethnic zoo that Prime Minister Yasuhiro Nakasone recently called less "intelligent" than Japan's menagerie. "In ancient Japan, they were lordless warriors," a blurb says. "Now, in New York, they have found a master." Ronin's chief villain is Prince Hiroo Matsushima, born in 1927 the last of a samurai family descended directly from Tokugawa Ieyasu. no one calls him Prince now, for "That had been forbidden since MacArthur. But everyone knew that after the imperial family itself, the Matsushimas were the most noble." "I was born a samurai in a world that no longer treasures their ways," Matsushima laments. His fanatic nostalgia for bushido resembles that of the novelist Yukio Mishima, a born-again samurai who disemboweled himself in a publicly staged fit of frustrated patriotism in 1970. Victory taxMatsushima feels that "the brunt of the changing tides in Japanese history had fallen in unequal measure on the shoulders of his family." He thinks that "It had become the policy of the Japanese government, and of the business community of Japan, to exact a victory tax from the United States and its people." "By stealth and dissemblement, postwar Japan had euchred from the world what it had been unable to wrest by force in the duration." Hence "the honor of the individual Japanese had been compromised almost beyond redemption . . . . Where bushido had reigned, now there was only guile." Matsushima likens himself to the industrialized samurai who carries a designer attache case and umbrella instead of two swords. "And in place of bushido there was the code of the modern businessman; implacable determination, unstinting effort, decision by consensus, and a subtle disregard for the conventions by which others find themselves found. Brooks Brothers and Vuitton. no vacations. Hard work. Group think. A wink at the rules. Victory for Japan." Mishima clonesThe alienated, obsessive-compulsive, manic-depressive Matsushima desperately wants to keep bushido alive. But he finds himself on the brink of suicide because "There were no other Japanese in New York yearning to return to the ways of their ancestors." This is all changed when Willie Lopez and his street friends try to mug "a little guy" who turns out to be the invincible Matsushima. Matsushima is impressed by Willie's fearlessness, and he sees in the boy his own redemption. Having discovered "the material of samurai" in others, "Bushido did not have to die with him. He could teach it to others. His example could be his legacy." Matsushima's material was "Not the hardened criminal, but the youth without hope." Beginning with Willie, he recruits twelve delinquent blacks, whites, and Puerto Ricans. The disadvantaged converts are given "strength through learning -- Zen and the martial arts -- the way of the samurai." They are taught that "To live like a samurai you cannot fear death." Not all of Matsushima's clones live up to his high expectations. He has to decapitate a Puerto Rican who had disobeyed his orders and killed a man. "Adolfo Reyes did not behave with the dignity of a samurai. Therefore, he was not granted the opportunity to die with courage (by committing seppuku)." In Matsushima's world, there is no margin for "errors in matters of loyalty and discipline." There is no room for people like Adolfo Reyes, who had "failed to control uncivilized instincts that were bred into his ancestors and worsened by life as a hoodlum in the streets of New York, uneducated, uncared-for, and unwanted." Double lifeThough Matsushima must keep his double life secret, "the gods knew that he was the daimyo with the smallest constituency in the world." His philosophy was "a unique blend of Zen Buddhist self-realization, and [his] borrowings from Alcoholics Anonymous." His clan members, though, needed risk and reward. They were not to be like yakuza ("Japanese men of low birth and poor manners"). But "For the samurai warrior in New York City in the 1980s, the only open road was crime." Matsushima's wife, Michiko, wonders why her "masterful lover" has become so exuberant and youthful. "I have found a place where I exercise," he explained. He had also found carnal solace in a "new young thing" named Han who was "wisplike and thin, without the stocky legs and foreshortened waist of most Korean women." She worked at the "Tokyo and Seoul Health Club" and "reminded him of one of the uniformed greeters at the department stores in Tokyo, babbling about the day's sales as you walked in the door." XenophobiaMatsushima allows himself to be called "Harry" by his American business associates. "One of the little games we play," he thinks to himself. "My name is Hiroo. There have been seven Hiroos in my family. When we come to America, we find American names to suit their limited ability to deal with the phonetics of other languages. Hiroo becomes Harry. Junichi is Jack. Akira becomes Andy. A small indignity to permit them to tell us apart without butchering our given names each time they wish to address us." Matsushima dislikes all geigin (Christian's corruption of gaijin). "His nose wrinkled at the thought of beefy white hands and beefy white faces, of the smells of barnyard veiled by the cheap scent of aftershave." Such visceral disdain for the racial kin of "MacArthur, the white shogun" proves Matsushima's undoing. His most immaculate plans are foiled by homicide Sergeant Arnold Ross, a martial arts expert who is clumsier and cruder than Matsushima, but is smart enough to trace some cadavers to his disciples and swing his euphoria back to suicide. Morbid dreamWhen other clansmen fail to toe the mark, Matsushima loses faith in his alien samurai. Realizing that his dream is doomed, he sends all but Willie to "glorious deaths" on a robbery he knows will fail. "He had indeed been mad to think that a tradition could be revived among the rootless in an atmosphere so foreign to its precepts." The sensitive and reflective Willie perceives the flaws in his master's morbid philosophy. "He did not pretend to understand all that he heard or read. He was a novice, and unschooled. Nonetheless, he know that Matsushima's answer had been no answer at all. In a period of days it seemed to Willie that Matsushima's continual striving for excellence in all things had had increasingly more to do with death." But Willie is too committed to quit or betray, and he avoids arrest by throwing himself out a window. Yellow perilMatsushima could have killed Ross, but instead he invites his now-respected rival to join him in a last supper. "Willie needed only the proper banner to follow," Matsushima explains. I gave him mine. My banner has not flown in too many centuries to be of use now." "They flew it at Pearl Harbor," Ross reminds him. "They flew it at Hiroshima," Matsushima replies. "It sells cars," Ross smiles. "For the Pearl Harbor of Toyota, there will be a Hiroshima too," Matsushima predicts. Matsushima gets Ross to "participate in the Japanese national pastime of flirting with death" by eating some blowfish meat. "I am only a master criminal," he confesses. "I have not been a leader of men, I have been a killer of men. I, who sought a glorious destiny, have succeeded only in drowning in my own pride and shame." Matsushima then eats the poisonous ovaries and liver, and dies with a fixed smile on his face. Christian's image of Japan is Matsushima. He makes no effort to balance Matsushima with a healthier Japanese character. His portrayals of Japan are singularly paranoid and pessimistic. In this sense, Ronin is in the mold of neo-yellow-peril novels like Olden's Dai-Sho, Steven Schlossstein's Kensei, John Brown's Zaibatsu, and Eric Van Lustbader's The Miko (collectively reviewed in The Japan Times on June 29, 1985). |