No non-tariff barriers in sight

Historical romance with a feminist touch

By William Wetherall

A version of this article appeared as

"Appreciating Asian men" in

Far Eastern Economic Review, Vol. 134, No. 41, 9 October 1986, pages 56-57

Blue paragraphs were cut from the FEER version.

Purple paragraphs were added to the FEER version.

Other phrasing may also differ from the FEER version.

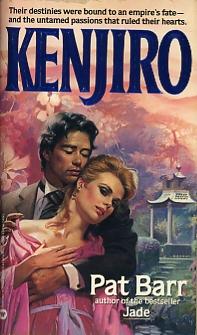

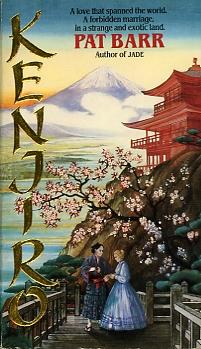

Pat Barr Kenjiro is what can happen when a female historian writes an entertainment novel set in the country of her expertise. The results are more educational than literary, but the story is compelling enough to keep reading. British historian and novelist Pat Barr's non-ficion books include The Coming of the Barbarians (The Opening of Japan to the West, 1853-1870), The Deer Cry Pavilion (Westerners in the Far East: The Sixteenth Century to the Present Day), Foreign Devils, and other titles mainly about 19th-century East Asia. Kenjiro is worth reading less for its story than for the feminist point of view from which it is told. English-language novels on Asia, particularly when it comes to sex, are predictable. The gluttonous White (or Black) heroes who devour yellow women and suffere indigestion from yellow men are probably the verbal clones of their non-Asian male creators. Barr's sympathies are clear, and while her messages are often obstrusive, they offer a refreshing alternative to the macho style of writers like Eric Van Lustbader in Ninja, The Miko and most recently Jian. Occidental novels that are set in the Orient are often inedible despite the exotic condiments that flavor their bland yarns. They are either over-spiced to suit the author's own bad tastes, or they overindulge the reader's appetites for nostalgia and fantasy. This may be what popular fiction is destined to be and do, though not a little "serious" literature is similarly projective and cathartic. Sexually, too, English-language novels on Asia are predictable. The gluttonous white (or black) heroes who devour yellow women and suffer indigestion from yellow men are probably the verbal clones of their non-Asian male creators, while the white heroines who prefer to dine with yellow men are most likely the literary offspring of non-Asian women who imagine, or know, that the world's ethnic cuisines can be mixed to please their palates too. Barr has written two romances about an English woman who finds much to appreciate about Asian men. Jade, first published in 1981 under the title Chinese Alice, is about an English missionary's daughter who was born in China and sees her father murdered in a 1870 massacre of Christians. "Held hostage, she and her brother are taken to distant Hunan, where, a child no longer, she finds herself first a servant, then the young concubine of the patriarch of the house of Chu", the dustcover explains. "It will be many years of captivity before she escapes ... only to find that she has little in common with the arrogant, stuffy Europeans who are supposed to be her own people." "We see the harsh clash of tradition and revolution through the eyes of a woman whose 'unladylike' intelligence and originality make her notorious among the Chinese and British alike -- a woman of great spirit and vision, ideally suited to bridge the chasm between two cultures that could not be more different", the blurb continues. "Alice will travel the length and breadth of China, and she will find love in many places: from infatuation with the [Chinese] man who initiates her in the rites of love, to Lin Fu-wei, the brilliant young radical whose passion she shares, but whose world she can never truly enter, to the Scottish journalist whose roguish devotion to adventure wins her heart for good." Kenjiro comes close to being a Japanese version of Jade. Elinor Mills arrives in Japan in 1862 about the time that an English man is killed by samurai clansmen who do not like the treaties which allow foreign barbarians to live in Japan. Elinor ventures to Japan from Hong Kong to visit her doctor brother, who secretly keeps a Japanese mistress but objects to Elinor's love for Kenjiro, a samurai interpretor and translator. One night, alert for anti-foreign extremists who might try to assassinate him, Kenjiro draws his sword on a shadow that turns out to be Elinor. Their friendship under the cherry tree quietly blossoms, and one day she realizes how much she loves him and imagines "a naked samurai with a sword held aloft above his head, with his penis in a state of large erection." Elinor thinks that Kenjiro loves her also but is simply too unsure of himself to say so. When she initiates a marriage proposal, he admits that he adores her too, and in their conjugal bed he confesses: "Why, I had my weapon ready for you the first time we met. Do you remember, my Elinor?" Barr dutifully and delightfully describes the sexual dreams and exploits of her major and minor characters, and quickly gets down to the business of boring the reader with anticlimactic tales of how interracial couples and children learn to cope with a hostile society. Though their culture shocks and adjustments are a century old, the impression is that the world hasn't changed much. Kenjiro is worth reading less for its story than for the feminist point of view from which it is told. Barr's sympathies are clear, and while her messages are often obtrusive, they offer a refreshing alternative to the macho missives of writers like Eric Van Lustbader a la Ninja, The Miko, and most recently Jian. Also deserving appreciation is the ironic resemblance between the interpersonal conflicts in the story, and the disputes that continue to complicate Japan's international relations today. After decades of marriage during which Elinor believes that Kenjiro is truly different from his compatriots, she discovers that he had been regularly visiting a prostitute, as was (and still is) the "custom" of married Japanese men who think they need (and can afford) such forms of stress relief and ego titillation. "It took me years to face the truth," she tells Kenjiro's sister, who had made a difficult conversion from Shinto to Christianity, and had become a spinster women's rightist when abandoned by an English sojourner she had lived with in sin. "You [Japanese] -- women included -- are surely the most intransigent people in the world. You conceal [this trait] quite carefully, as a courtesy to strangers, but you are unalterable, inexorable. Fads, fancies, and fashions wash over you, but you drop down into the same sand always, hard as pebbles, unchanged at the core." The main story is told around several mini stories which involve minor characters. Some of these smaller stories are more engagingly told than the main one, which sometimes reads like a hybrid of a Harlequinesque saga and a thesis on social change in colliding cultures. Barr occasionally rewards the reader's patient labido with a morsel of hardcore erotica for no obvious literary reason, in the vein of other genre writers who are much more inclined than she to lace their exotic tales with sex for its own sake. But only by association is she guilty of the unfulfilled promises made by the lusty cover art of the American paperback editions of both Kenjiro and Jade. Nor may Barr herself approve of the advertising blurbs which have the heroine coming to "Imperial Japan" in the middle of the 19th century, though she does invest her European characters with an awareness of their "isolated, precarious position on a confined and swampy fringe [Yokohama] of an unknown oriental empire". During the first part of the story, Japan was in a state of civil war and had not yet restored to its so-called "emperor" the imperial authority that by the novel's end was intentionally being used to build a true empire. Cover art buffs will want to buy both the British and American paperbacks. The British edition cover is more like a Chinese print in which the people are conspicuously lost in the landscape. Elinor is admiring Kenjiro's prideful swords, though both are sheathed. Freudian gestures are less evident on the American cover, which shows the two lovers dominating nature while eyeballing only each other and the reader. The scene on the spine of the book is aimed at supermarket display rack browsers, who are tired of the interracial sex which practically defines the southern plantation novel, but are hooked on the visual lures of this closely related genre. Original ending -- Elinor is running an assertive peachtone thigh down Kenjiro's number-one swarthy hand. And not a single non-tariff barrier in sight. FEER ending -- Kenjiro's swarthy hand strokes Elinor's peachy thigh with obvious relish. And there is not a single non-tariff barrier in sight. |