Backpackers, sojourners, settlers

Fleeing demons and pursuing happiness at home and abroad

By William Wetherall

First posted 15 August 2006

Last updated 12 August 2024

Wanderlusts Yankee hobo • Backpack fables • Illusions • Hippies, slakers, bratpackers • Going native • Personality • Celebrity writers

Titles by author Reviewed by publication date Titles in red will open in new window

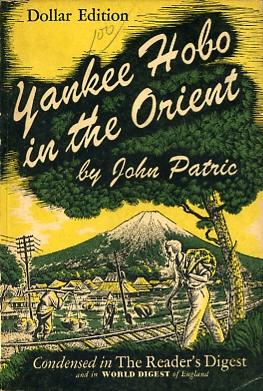

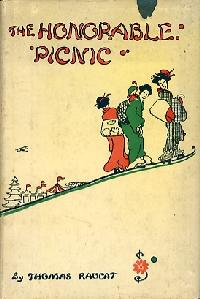

Thomas Raucat 1924, 1927L'honorable partie de campaigneThe Honorable PicnicThis novel, first published in French as L'honorable partie de campaigne (1924), then in an Engish translation as The Honorable Picnic, is a romantic romp set in Japan in the 1920s. It was written by Roger Poidatz (1894-1976), signing as Thomas Raucat, a Franco-Japanese pun reading "Tomarō ka?" -- literally "Shall [I, we] spend the night [shack up] [here]?". Reissued after World War II, perennially praised by Donald Richie, and recommended reading in some anthropology courses in the United States (George De Vos at Berkeley, for example), it has gained the status of a "classic" among novels about Japan in French and English. French editionsThomas Raucat There are many prewar and postwar editions. And a deluxe 2-volume illustsrated edition, with a slip case, was published in Paris in 1944, during the Pacific War, when France was occupied by Germany and its Vichy government was allied with Japan in French Indochina. There is also an edition bound with a blue ribbon between board covers that show only the title, vertically, in three large graphs -- 御遠足 -- read "Go-ensoku" and meaning "Honorable-picnic"). English editionsThomas Raucat Thomas Raucat There are currently many POD offerings of the English translation, which is now in public domain, including the following Routledge edition. Thomas Raucat Spanish editionThomas Raucat German editionsThomas Raucat Italian editionsThomas Raucat Promotional blurbsThe dust jacket of the second (December 1955) Viking printing of The Honorable Picnic bears these blurbs.

Time Magazine reviewThe Time Magazine review cited on the front flap of the December 1955 Viking printing appeared in the 15 December 1955 edition of the magazine. The full review reads like this (copped and typographically adapted from Time.com.

|

Brad Leithauser 1985Equal DistanceBrad Leithauser Forthcoming. |

Ross Davy 1985Kenzo: A Tokyo StoryRoss Davy Brisbane-born Ross Davy had lived in Melbourne and Tokyo at the time this novel was published. The back cover hints at most of what it is supposed to be about. Two Australian women are in Tokyo studying Clinically ambitious, intelligent Harriet remains Blonde, dreaming Linda is attracted to Tatsuo, His love Kenzo, a novice Zen priest, tries A PERSONALITY SPLITS APART In the novel, the characters appear in the opposite order. Halfway down the first page, Kenzo spots his love Tatsuo from a footbridge he is crossing, and we see Tatsuo through his eyes: "his nipples make tiny points under his t-shirt" (page 3). When Tatsuo notices Tatsuo, Tatsuo rushes up to him and they "push each other for boyish joy" (page 4). By the time their Australian friend Linda arrives, halfway down the second page, we learn that she teaches English, studies Buddhism, and is always late. We are told "she is late probably having stopped to chat to a yakitori-seller or maybe from having had to turn back to punch someone on the train who had put his hand up her dress" (page 4). When Linda arrives, "Tatsuo and Kenzo give her a friendly shove each and they all laugh" (page 4). DisclaimersAt this point, if you've read the front matter, you go back and reread the two disclaimers.

This made me wonder if the disclaimers were part of the plot. The plot thickensThe second page continues with this parenthetic break in the narrative as we are told something in another voice (page 4).

The threesome head for a disco, and by the beginning of the third page Tatsuo has gone home as he has to leave for Okinawa the next morning. Kenzo dances with Linda for a while and then she also leaves. By the middle of page three, Kenzo has allowed himself to be picked up by Yoshiki. The boys go to a nearby "'Love Hotel'" (as Davy writes it), and Kenzo showers but is "convinced his genitals stink as Yoshiki stuffs them into his mouth" (page 5). The story is very quickly paced. Unlike a daily soap opera that you can miss for several weeks and still pick up the thread, skip two pages in this book and you are likely to have to go back and read them to figure out why suddenly nothing makes sense. If, that is, you want a lot of semen along with your enlightenment. |

Jay McInerney 1985RansomJay McInerney Back cover hypeThe Vintage Contemporaries edition gives the longest account of what readers can expect to find in Ransom. Ransom, Jay McInerney's second novel, belongs in the distinguished tradition of novels about exile. Living in Kyoto, the ancient capital of Japan, Christopher Ransom seeks a purity and simplicity he could not find at home, and tries to exorcise the terror he encountered earlier in his travels -- a blur of violence and death at the Khyber Pass [on the border of Pakistan and Afghanistan]. Ransom has managed to regain control, chiefly through the rigors of karate. Supporting himself by teaching English to eager Japanese businessmen, he finds company with impresario Miles Ryder and fellow expatriates whose headquarters is Buffalo Rome, a blues-bar that satisfies the hearty local appetite for Americana and accommodates the drifters pouring through Asia in the years immediately after the fall of Vietnam. Increasingly, Ransom and his circle are threatened, by everything they thought they had left behind, in a sequence of events whose consequences Ransom can forestall but cannot change. The Flamingo edition cites a Playboy review of Ransom (Fontana) which said, "'The hardest thing about writing a critically acclaimed first novel is coming up with a second.'" Though both editions pitch Ransom (1985) as McInerney's second novel, and otherwise give the impression that he wrote it after Bright Lights, Big City (1984), he actually wrote Ransom first but was unable to publish it. Linguistic parityOne thing McInerney does well in Ransom, that many writers fumble with, is interject Japanese words directly into English as though they belonged there. McInerney resists the temptation to be a language teacher by defining all the terms he uses -- or, as bad, to exotify Japanese expressions with italics. Whether this was McInerney's idea, or that of an enlightened editor, I cannot say. Many writers who want to treat Japanese and English words in a story equally are overruled by unimaginative, by-the-rule editors who insist on marking every word not in their English dictionary or spelling checker with italics. When you pick up a novel set in Japan and see it sprinkled with italicized words, and glosses embedded in the narrative, you know the writer is more interested in teaching you Japanese than telling you the best possible story. SenseiOn the first page alone readers encounter "karate-ka" and "dojo" and "sensei" as though they had every bit as much a right to exist in an English sentence as "eyes" and "huddle" and "faces". Readers have read "sensei" a number of times by the time they encounter this exchange some 15 pages into the story (pages 16-17).

This is the only time in the book that "sensei" is italicized with the intent of marking it apart from other words in the same sentence. Here it is not only an object of linguistic interest, but it has an exotic ring to the ears and in the mind of the girl. The way Miles expands on the implications of "sensei" beyond just a "teacher" is par for the course in novels that attempt to teach something about Japan while telling a story. McInerney could easily have avoided such a language lesson, but arguably Miles is the sort of seasoned gaijin who likes to explain such things to FOBs like the girl. Irene Webster-Smith, too, was once FOB in Japan. She herself came to be called Sensei -- the title of her biography.

HonchoIt is not clear whether McInerney intended to be ironic when he included "honcho" in the English definition of sensei. The word naturalized into English from Japanese "hancho" in the 19th century, probably on plantations in Hawaii. Honcho can stand alone, but "head honcho" has become just as common. The "head" may seem to explain "honcho", but it is better understood as an alliterative ornament like "big" and "main" in "big boss" and "main man". Honcho is even the title of a western novel.

Tour guideMcInerney is inconsistent, though, as in the following scene (pages 9-10). You're improving, Ito said. The second bout you almost scored with that mawashi geri. Soon you'll be defeating me. Ransom protested that he was a rank beginner, although he was in fact rather proud of his second bout. What he told Ito, however, was something to the effect that he was no good and never would be. The Monk disagreed. He was already good enough for a kuro obi, the black belt. Oh, no, not at all, Ransom protested.This was all terribly Japanese. McInerney makes two mistakes here. Up to this point, he has thrown out a number of karate terms without a word of commentary. Why, then, the "black belt" gloss for "kuro obi"? His second mistake to not to simply dramatize the verbal game Ito and Ransom are playing, and leave it to the reader to decide whether it is "terribly Japanese". As it is, a reader cannot be sure if the remark is Ransom's or McInerney's -- and if not Ransom's, then why is it there? |

|||||||||

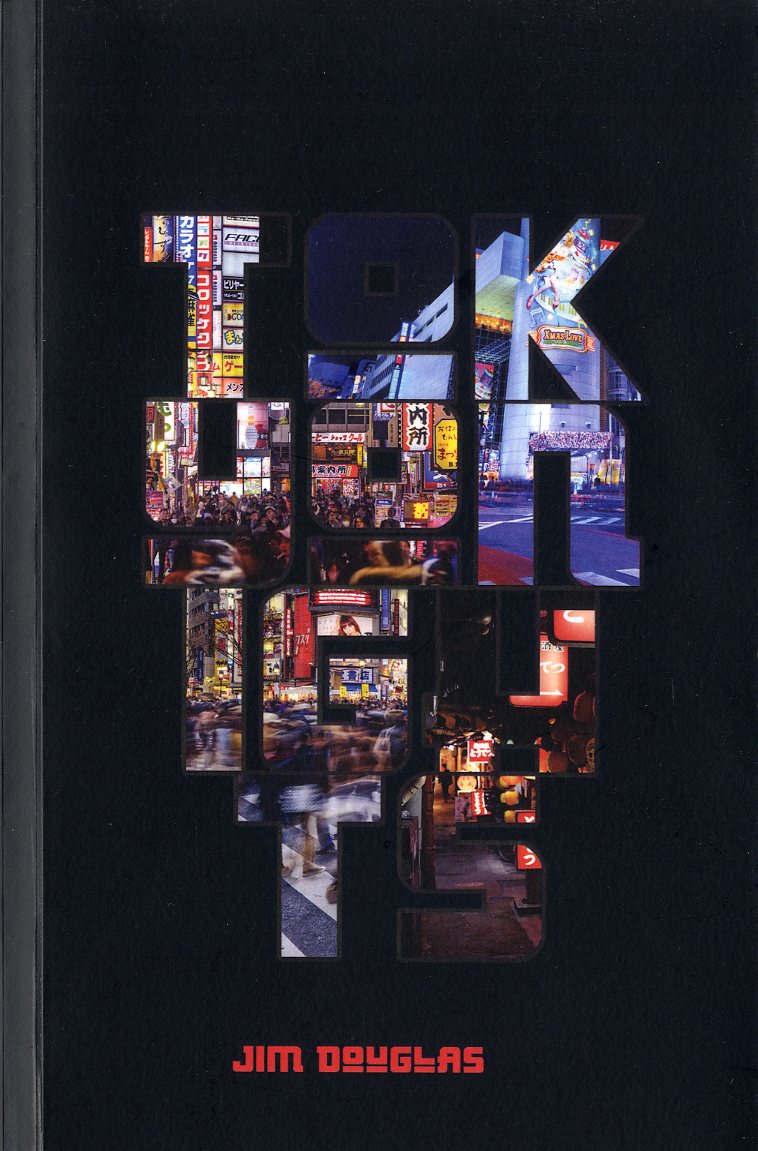

Jim Douglas 2016Tokyo NightsJim Douglas Backcover synopsis |

||||

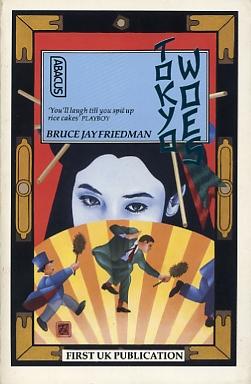

Bruce Jay Friedman 1985Tokyo WoesBruce Jay Friedman Backcover synopsisThe UK edition introduces the story like this. Mike Halsey was driving along one morning, going for the papers, when this feeling swept over him. The last time it happened he would up in Finland. This time it was Japan. He'd never been there, of course, though he sat through three-quarters of a Kurosawa festival once. He didn't speak the language or even like sushi that much, and when he thought of Japanese technology he thought of something you could wear on your wrist that told you tomorrow's weather. But he had this urge. He guessed there was more out there than he suspected but, oh boy, he had yet to learn about noddle factories, seductive brain-squeezers, electric futons and Peeping Tom bus tours. As prosaic and dull as the blurb may be, at least it is short. The story -- which begins on page 11 and ends on page 187 -- rambles on for nearly 187-11 pages too long. It is, however, one of those stories that, if you are a student of such fiction, you have read whether or not you want to. It is not that Friedman, a fairly successful writer, is "bad" at what he has generally does for a living -- but more a matter of his having chose the wrong subject for his brand of humor -- at a moment in his life when perhaps he had to write such a book simply to work out some passing personal problems (see "Biographical note" below). Mike meets Bill AtenabeOn the plane Mike meets a man about whom the narrator explains -- "There was no question that he was Japanese, although Mike felt there might have been someone from Illinois in the picture as well" (page 26). He appeared to be Mike's own age -- mid to late thirties. The two men find two empty seats so they can sit together. "Mikes new friend introduced himself as William (call me Bill) Atenabe" (page 26). Mike tells "a small wiry Japanese old-timer next to him, blowing cigarette smoke in his face" to knock it off. The man, "who had a close-cropped military-style haircut, waved an arm at him in a threatening manner and took a few quick spiteful puffs in Mike's direction" -- and Mike was about to "grab the fellow and put an end to his rudeness" -- Bill -- "his friend" -- intercedes -- and said the fellow was his father, Poppa Kobe, and not to mind him. "He held out in the jungles of the Philippines for two years after the war ended . . . and frankly, he's still a little anti-American" (page 27). "brought to Japan . . . on death march"The story gets quirkier, sillier, and dumber by the page. In the end, we really know very little about Mike Halsey, Bill Atenabe, Poppa Kobe, Momma Kobe -- or Lydia (page 53).

"once a gaijin"One day Mike finds Bill in the teahouse, where he had "laid out a ceremonial mat and was sharpening two swords, one long, the other short" (pages 166-167).

Bill finds reason, in a woman, to live for another day, and Mike decides it's time to return to the States and his wife Pam, who he calls from San Francisco. As he nears their home, he notices lanterns strung along the rafters and smells incense through the screen door. Inside, Pam is waiting for him, wearing a kimono, "her hair brushed up in a bun with an ivory comb stuck through" (page 184). On the dining-room table there is tuna sashimi fresh from the dock. First, though, Pam wants Mike to come upstairs, where she was "just assembling one of those straw mats" and help her (page 185). Mike, though, is "Japaned out" and wants only a drink -- and time to think about whether he had a great time in Japan. Biographical noteBruce Jay Friedman is not a tourist turned writer after a stay in Japan. Born in 1930, he received a BA in journalism from the University of Missouri in 1951, in time to serve in the US Air Force from 1951-1953 -- which corresponds with the Korean War. One article about him states that "During the Korean War First Lieutenant Friedman "got flown around America, taking pictures and writing stories for an Air Force magazine" (Nick Fowler, "Bruce Jay Friedman: Making Sense of Entropy", The Antioch Review, 2005). After the war, Friedman edited some men's magazines while writing short stories. After the success of his first novel, Stern (1962), about a paranoid Jewish man who moves his family from the city to the suburbs, he began getting work writing scripts for movies and plays, and some non-fiction. Tokyo Woes, which came after an eleven-year hiatus, is the fifth of eight novels he had published as of this writing (2010). AP Books Editor Phil Thomas described Friedman as "an amiable man whose droll way of observing life highlights his books, most recently the novel 'Tokyo Woes'" ("Wide variety of writing grist for Bruce Jay Friedman's mill", The Gettysburg Times, 13 July 1985, page 17). Tokyo Woes, written in the mid 1980s when he was in his mid 50s, suggests that he was eager to live up to his reputation, and otherwise rest on his laurels, as a writer of bland black humor. Thomas quotes Friedman to have said that he was divorced at the time he got the idea for Tokyo Woes. He was wary of "relationships" (he hates the word), was fascinated by things like his TV set, and this led him to "read all kinds of stuff about the Japanese, even the yellow pages of the Tokyo telephone book" (ibid.). Thomas calls the novel "a wild and witty look at contemporary Japan through American eyes" -- and says Friedman described himself as "a serious man whose thoughts get expressed comedically" (ibid.). |

||||||

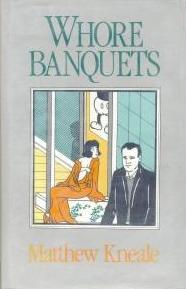

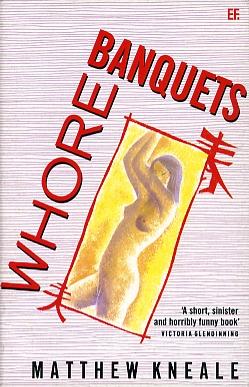

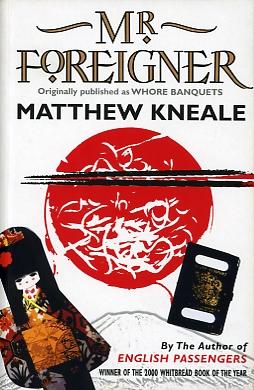

Matthew Kneale 1987 (original title)Whore BanquetsMatthew Kneale 2002 (revised title)Mr. ForeignerOriginal title editionsMatthew Kneale Revised title editionsMatthew Kneale Kneale, born in 1960, turned 26 in 1986. He began writing Whore Banquets while in Japan, where he lived for a year after graduating from college in modern history. Prizes galoreA blurb on the back of Mr Foreigner (there is no period after "Mr" on the title page) informs us that "MR FOREIGNER was Matthew Kneale's fist novel and won a Somerset Maugham Award in 1988." The cover tells us that he is the author of English Passengers, winner of the 2000 Whitbread Book of the Year. Does winning literary awards run in families? Nigel Kneale won the 1950 Somerset Maugham Award for Tomato Cain and Other Stories (1949), a collection of short fiction. In 1988, his son Matthew Kneale won the same prize for Whore Banquets (1987). Whore Banquets got some literary attention before it was published. It was a runner up for the 1986 Betty Trask Prize, which is given to published or unpublished first novels "of a romantic or traditional nature, i.e. not experimental" written by a Commonwealth citizen under 35 years of age. Turns to the pastKneale's third novel, Sweet Thames (1992), set in London in the 1840s, won the John Llewellyn Rhys Prize in 1992. His fourth, English Passengers (1999), about a group of Englishmen who sail to Tasmania in the 19th century looking for the the Garden of Eden, received the Whitbread Novel Award and was also named the Whitbread Book of the Year in 2000, and was also short listed for the Booker Prize for Fiction that year. Cover blurb problemsThe blurbs the back covers of the paperback editions of Whore Banquets and Mr. Foreigner unwittingly tell us what is wrong with the novel. Whore Banquets (Dent, 1988)

Mr. Foreigner (Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 2002)

The copy writers, like the author, apparently thinks it is the object of fiction to lead readers to an understanding of someone's "culture" -- rather than reveal the human condition through drama driven by character. Contrary to the implications of the blurbs, one gets the impression that both Daniel and Keiko are losers precisely because of personality faults having nothing to do with one being British and the other being Japanese. The novel is padded by asides that amount to "I was there" glimpses of Japan -- or at least what Kneale seems to want the reader to think about Japan. Structural paranoiaOther than for shock effect, "Whore Banquets" has little justification as a title -- whereas "Mr Foreigner" aptly reflects the paranoia that runs through the entire narrative. "Mr Foreigner" -- the title by which the novel is now known -- reflects the term "gaijin san" (page 15).

"Gaijin" (outsider) -- a reduction of "gaikokujin" (outlander) -- is commonly used to refer to people like Daniel, who are racially conspicuous in Japan, whether or not they are foreigners. It it used with the same racialist reflex that brings labels like "white" or "black" or "Asian" or "westerner" or whatever to the lips of most people in the world everyday. And Daniel's ears have become very sharply attuned to the word. The above scene, coming in the second chapter, structurally sets up a similar scene in the final chapter (page 153).

The two scenes are structurally parallel right down to the qualifications of the triumphant shouting as "half-polite" and "empty of malice". Being seen and treated as a nameless alien from a distance when not up close, from the time he sets foot in Japan to the moment he makes his escape, is as central to the theme of the novel as it is to Daniel's personality. Shameful delusions of referenceOne cannot dismiss usually good-natured (however racially elicited) shouts of "Haroo" (not "Hurro") and "Gaijin da!" as imaginary. But what about how people merely look at Daniel, or otherwise behave in his presence? In both the first and second chapter, Kneale narrates an instance in which Daniel thinks he has been noticed as a "westerner".

In other scenes, too, Daniel feels that he is being observed. And "shame" crops in a number of comments about Japanese society. CaricaturesDaniel is not exactly a sympathetic character. He and the Australian Jake are marginally more convincing than the American Samuel Echtbein. Keiko is the most credible Japanese character, but even she is more contrived than any of the foreigners. Echtbein, who has gone native and fancies himself an expert on all things Japanese, is described as "the only other foreigner" living around Daniel (page 3). He was barely distinguishable as a westerner -- his hair was closely cropped in the Japanese style, while his eyes were concealed behind thick glasses. The squinty-eyed immigration investigator could have been rendered less visible or at least more clever at his job. The Chibas and Keiko's family are the least likely characters. Seasoned readers or literature will realize that all of Kneale's characters are caricatures -- but those who have not lived and worked in Japan will have difficulty knowing there the character ends and the human begins. Uneven touchIn the hands of the best story tellers, details reveal character, establish foundation for behavior, and are presented in a manner that keeps the reader guessing but never frowning. Good novels are like even the worst movies, in that a gun shown in a drawer on the first page gets used by the last page -- or is not shown. The pleasure of reading is thus to anticipate how something, or someone, introduced in an earlier chapter will figure in a later chapter -- be surprised. Whore Banquets has its share of surprises -- but, as short as it is, it could have been pared down twenty or thirty pages. One gets tired of reading how the protagonist (or the author, one is never sure which) thinks "Japanese" react to "westerners" in public. And the first trip Daniel makes to Takao to find his passport is a waste of ink. It is easy to understand why Whore Banquets attracted attention and why Matthew Kneale went on do collect more awards. It is clear by the end of the story that he has the touch -- though not all parts received its benefit. See Whore Banquets for a review of this novel by Mark Schreiber, under its original title. |

|||||||||||

John Burnham Schwartz 1989Bicycle DaysJohn Burnham Schwartz You will not read many blurbs as sentimental as the one on the back of the Plume edition of Bicycle Days. Blissful memories of learning to ride a bicycle in Central Park, his mother running behind to catch him when he fell -- these are Alec Stern's treasured "bicycle days," and the title of John Burnham Schwartz's stunning debut novel. Alec's postgraduate summer from Yale is spent living and working in Japan -- and all-American boy thrust into a culture where he is, for once, the outsider. A series of flashbacks connects Alec's past and present -- crisp days in the park, long blurred by more painful memories of the now fractured family he has left behind -- as he struggles to master the customs of his new country, earning the trust and companionship of his host family's infinitely patient and lonely mother, and embarking on a bittersweet love affair with a beautiful Japanese woman. BICYCLE DAYS is a story of journeys -- foreign and familiar -- and of needing to be both set free and held close, as in the bicycle days of childhood. Schwartz's novel unfolds in forty thematically-titled chapters, which average about six pages each and read like short stories. The better chapters show life in Japan through verbal vignettes. Too many chapters, though, read as though they were written by a tour guide who doesn't know when to shut up -- like this episode (page 25). The receptionist was looking at him. "Yes, herro. Can I help, prease?" Distantly, Alec noticed that she was no longer on the phone. "Oh. Yes." She gave him a hesitant smile. Almost encouraging, he thought. "And, so, who see?" I'm Alec Stern," he said. Just moment, prease." She started flipping through a little book, found a page, and traced a list of names with her finger. The finger went to the bottom of the page, then back up again. Alec shook his head. "I'm Alec Stern. I'm supposed to start work ehre today. First time. She let out a brief giggle, and her hand flew to her mouth to cover it. "First time, too," she said, indicating herself by touching the tip of her nose with her index finger. Really? Your English is very good." Switching to Japanese, he added, "What is your name?" Her face turned red, the hand went up again, curved and feminine. "Keiko." He put his own hand forward, holding it just above the desk. "I am Alec. Nice to meet you." As he said it, he realized that the literal translation from the Japanese was something like "Please look after me." Keiko went through a brief struggle over what to do with her hand. Alex watached as it hesitated between the two points. Suddenly she grabbed his hand, shook it once, then quickly voered her mouth again. |

T. Coraghessan Boyle 1990East Is EastT. Coraghessan Boyle The 2nd chapter of Part 1 opens like this (page 11). HIRO TANAKA WAS NO MORE CHINESE THAN SHE WAS. HE WAS A "On the day in question" begins the next graph, and 3 pages later, still dramatizing Hiro's leap into the infinite, Boyle depicts Tanaka's dispute with the ship's 1st and 2nd cooks Chiba and Unagi, with whom Tanaka was drinking (page14). [Chiba] turned to Unagi. "Did you ever hear of such a thing?" Unagi's eyes were slits. He rubbed his hands together as if in anticipation of some rare treat, and he bowed his head with a quick snap. "Never," he breathed, waiting, waiting, "except maybe among foreigners. Among gaijin" Now Hiro looked up. The underlying cause of his explosion, the cause of all his torment in life, was about to surface. Chiba leaned into him, his monkey face twisted with hatred, flecks of spittle on his upper lip. "Gaijin," he spat. Long-nose. Ketō. Bata-kusai." And then he unfolded his clenched fist, studied the plam of his hand for an instant, and without warning struck a savage blow to the bridge of Hiro's nose. . . ." Predictably -- because by now the purpose of Boyle's narrative is clear -- "gaijin" and "ketō" and "bata-kusai" are the object of a language lesson and an explanation of Tanaka's "loss of control" in reaction to Unagi's assault, which resulted in Tanaka being thrown in a makeshift brig (page 15). Gaijin. Long-nose. Butter-stinker. These were the epithets he'd endured all his life, crying to his grandmother on the playground, harassed in elementary school and transformed into a punching bag in junior high, singled out and bullied till he was driven from the merchant marine high school his grandmother had chosen for him. Foreigner, that's what they called him. For while his mother was a Japanese -- a firm-legged beauty with round eyes and a fetching buck-toothed smile -- his father was not. No. His father was an American. A hippie. A young man in a cracked and rubbed-soft photo, hair to his shoulders, the beard of a monk, eyes like a cat's. Hiro didn't even know his name. . . . The back cover describes the novel as "A sexy, savagely hilarious cross-cultural tragicomedy about a young Japanese seaman who jumps ship off the Georgia coast -- and swims into a net of genteel ladies, descendants of slaves, rabid necks, and the denizens of an artists' colony on the grounds of an old estate." As a story idea, it's not bad. Boyle has a B.A. in English and History (1968), an M.F.A. (1974), and a Ph.D. (1977) in English, and was later a professor of English at the University of Southern California. He has published nearly 20 novels and over 150 short stories as of this writing in 2023. In 1988, two year before the publication of East is East, he won the PEN/Faulkner Award for World's End, an historical saga of upper New York, and for a moment he became was the flavor of the day in New York literary circles. Michiko Kakutani, reviewing East is East in The New York Times, described it as "A hilarious black farce about racial stereotypes, selfish dreams, and ambitions run hopelessly amok . . . It's a pastoral version of The Bonfire of the Vanities (back cover promo). East is East is, for me, an over-written story that could have been told in half the words if Boyle had reigned in his impulse to write two or three phrases where one would have done, and explain things that would have been quicker and more engaging for the reader if simply dramatized without comment -- and his urge to use his protagonist as a foil for displaying his knowledge of actual and imaginary things Japanese. |

Clive James 1991Brrm! Brrm!Clive James Forthcoming. |

Alan Brown 1996Audrey Hepburn's NeckAlan Brown Early US paperback editionsNew York: Pocket Books, July 1996 New York: Pocket Books, circa 1997 Unlike most sojourner fictionMost fiction set in Japan is poorly written, even by good guide-book or journalistic standards. Few works deserve reading as literature. This novel is somewhat of an exception. Brown has mastered the difficult art of capturing vignettes that read very much like short stories. Structurally Audrey Hepburn's Neck is a fairly skillfully stitched quiltwork of scenes that rarely fail to develop plot and character. Unlike most writers of sojourner fiction, Brown prefers to dramatize life in Japan through his characters, rather than make narrative statements about Japan. Brown captures the emotions of his principle characters with great sensitivity, while using other characters as vehicles for social parady. Interracial obsessionsThe entire story is about interracial sexual obsession -- and, like practically all writers, Brown racializes Japanese and foreigners. Toshi, a young man from Hokkaido who likes foreign women, comes to Tokyo and finds himself picked up by Paul, who turns out to be gay. Toshi doesn't respond to Paul's overtures, but the two men become best friends and confide in each other -- Toshi about his white girlfriends, one of whom has a fetish for Asian men and several behavioral disorders, and Paul about his Asian boyfriends and frustrated quest for a lifelong partner. Toshi was raised by his father, and not until late in the novel does Toshi begin to learn why his mother left home. I will not spoil this element of the plot -- except to say that it was too contrived and spoiled the novel as a story about friendship and love. Japanese translationアラン・ブラウン <Alan Brown> Both the author's afterword to the Japanese edition (pages 289-292), and the translator's afterword (pages 293-298), are dated September 1997. Brown's simple, clear style easily morphs into Japanese, and Nawa's rendering is very faithful. She even restrains from resolving the ambiguity of some of Brown's proper nouns -- preferring to express them in katakana rather than commit to one of several choices in kanji. For example, Okamoto Toshiyuki is オカモト・トシユキ, and hence Toshi is トシ, and his father Fumio is フミオ. "stooped Korean women"Audrey Hepburn's Neck has a number of flaws that make some of Brown's snapshots of life in Japan not just fictional but false. Take the following scene (page 66, underscoring mine) Shinjuku Station. On platform twelve, trains arrive and depart every forty-three seconds. "Move quickly! Don't fall off the platform! Work hard today!" a recorded voice booms as the crowds are herded along by a battalion of white-gloved men, shoved through the doors of cars already filled to twice their capacity. The doors shut behind him, and Toshi turns to look out the window. On the platform, stooped Korean women wearing surgical masks sweep up shoes, briefcases, umbrellas, and magazines, drop them into bins marked LOST AND FOUND. Nawa did not often depart from Brown's metaphors, but she morphed "stooped Korean women" into 腰の曲がったコリアンの老婆ら (koshi no magatta Korian no rōba-ra) -- which back translates "bent-backed Korean old ladies" (Japanese, page 67). Where Brown had let "stooped" suggest how old the "Korean women" might be, Nawa expanded "Korean women" into "Korean old ladies". コリアン (Korian), a katakana derivation from English "Korean", is seldom used in Japanese, and then mainly to refer to "Koreans" as a racial cohort without reference to nationality, which could be Japanese. The most familiar expressions are 韓国人 (Kankokujin) and sometimes 朝鮮人 (Chōsenjin), the former referring to a "national of the Republic of Korea", the latter to a "Chosenese" or "affiliate of the [former] Japanese territory of Chosen". Since Brown has characterized the women as simply "Korean", Nawa had no choice but to translate the term コリアン. Brown, projecting his narrator's voice through Toshi, has called them "Korean", but "Korean" is a generic English term, more a "race box" than a civil nationality. The rush hour scene is humorously larger than life, but the exaggeration has some foundation in rush hour reality. How, though, does Toshi know that the women are "Korean"? Do the women somehow "look" Korean to Toshi? Are the eyes he glimpses above the masks when the women unstoop and glance toward him "Korean"? Are their clothes or shoes "Korean"? Is their manner of sweeping (or are their brooms) "Korean"? Or has someone told this man from Hokkaido that the "stooped women" who clean the platforms at Shinjuku station in Tokyo are "Korean"? Or did Brown shortlist some "social issues" he wanted to touch upon, including the "Korean minority" in Japan? And decide to make this ellipitcal reference to their rumored "underclass" status? |

||||||

Alex Garland 1997The BeachAlex Garland The edition shown here is an early tie-in edition for the forthcoming movie adaptation advertised on the cover. The story -- by 26-year-old British writer Alex Garland -- had become a bestseller, and was widely acclaimed as one of the best novels written by an author younger than 30 -- a Lord of the Flies of the X Generation, dramatizing its search for meaning in a world infested by video games and vapid material culture -- and its disillusionment when finding more of the same or worse. The pacing is extremely fast -- 11 parts prefaced by a page titled "boom-boom" -- a page from the the Vietnam war -- which begins "Vietnam, we love you long time. All day, all might, we love you long time" -- and ends "Yea, though I walk through the valley of death I will fear no evil, for my name is Richard. I was born in 1974" (page 1). Each part contains several short segments, and all parts and segments bear snappy titles, several with allegorical echoes of the Vietnam War, which branded the generation that spawned Generation X -- and Richard, the narrator. The first part is "bangkok" -- the first segment is "bitch" -- and the first line is "The first I heard of the beach was in Bangkok, on the Ko Sanh Road. The Ko Sanh Road was backpacker land" (page 5). Richard and a few other like-minded backpackers head for the beach, which is rumored to be unsullied by human civilization -- only to find that it has already been occupied by a people bent on keeping out newcomers while clinging to elements of the life they supposedly left behind, and struggling to deal with the sort of emotional divisions that plague all human communities. Garland wrote the novel while living in the Philippines. In the book, Richard is British. The film adaptation, directed by Danny Boyle and released in 2000, stars Leonardo DiCaprio as Richard, who in the movie is an American. Read the book first -- then watch the movie -- as a study how badly a studio film produced on a big budget and scripted to appeal to the masses, can compromise the power of a story with gratuitous romance, brighter endings, and Americanization. |

William Sutcliffe 1997Are You Experienced?William Sutcliffe Forthcoming. |

David Galef 1998Turning JapaneseDavid Galef David Galef is profiled inside the back cover as a "displaced New Yorker" who "has lived in Jew Jersey, Massachusetts, and Osaka" -- and who, at the time, was teaching literature and creative writing at the University of Mississippi. Earlier versions of some of the chapters of Turning Japanese are attributed to six periodicals, including Kansai Time Out. Presumably these are included in the "over sixty short stories" he is said to have written as of 1998. The photograph on the back cover shows Galef sitting on a bench wearing geta with unusually high teeth -- at least much higher than those of the geta I used to wear when living at a geshuku in Urawa, now part of Saitama city. He looks relaxed -- neither sad nor happy. That's sort of how I feel now. The main element of interest in this rather lamely narrated story -- burdened with language lessons and other typical shortcomings of a sojourner novel written on the fly -- is the twist of "turning Japanese" after leaving Japan. The blurb inside the front and back covers starts off with a glaring typo that characterizes the story (highlighting mine). G [sic = Go] ni itte wa, g [sic = go] ni shitagae, runs an old Japanese proverb: Obey the customs of the village you enter. Just don't overdue things. It may already be too late for Cricket Collins, a recent Ivy League graduate who travels to Osaka for his first real job as an English instructor. The time is late 1970's, with Japan fast becoming the new find-yourself region that Europe was to the backpack set in the 1960's. From pachinko parlors to paper cranes and tea ceremony to translation problems, everything is entrancing to Cricket at first, as he throws himself headfirst into a two-thousand-year-old culture. But soon he gets kicked out of his teaching job at Kansai Gakuin for petty theft, and on a brief trip to Korea he gets embroiled in a sexual misadventure with painful after-effects. Spinning slowly out of orbit in his free-floating expat existence, he starts to lose touch with family, friends, and reality. It isn't until he returns home to America that he begins to turn Japanese with a vengeance. Turning Japanese is as much about the allure of a foreign culture as it is about the divided existence of an expatirate -- and the terrors of one's own mind. Be careful of breaking down the barriers between two cultures: the breakdown you create may be your own. The final paragraph practically defines the harder core of the "sojourner" genre. However, if true that "the breakdown you create may be your own" -- and if true that breakdowns are mostly matters of personality and otherwise what Kipling would have called "neither East nor West, Border, nor Breed" -- then "the barriers between two cultures" are also best thought of as your own. |

Simon Lewis 1998GoSimon Lewis Wales-born Simon Lewis was originally known as a writer of travel guides to places he had lived in various Asian countries. His fame spread with the publication of Go, his first novel, which takes "backpacker and sojourner" fiction to a new height in high (and sometimes black) humor. Back cover synopsisPROBLEMS AT HOME? It's time to go Lee, Sol and Vix are on the run -- from police, gangsters, parents . . . themselves. As they travel through Asia on separate quests, their paths cross. But it doesn't matter how far you go, reality always catches up with you . . . Set mainly in Brixton, Goa, and Hong Kong, Go clearly shows the construction lines of Lewis's own real and imagined travel adventures. Its 28 chapters -- grouped in 7 parts -- are individually titled and read very much like short stories. Shamelessly funnyThe start of story 9, "wedding snaps", illustrates Lewis's infectious irreverent style (page 127). wedding snapsI was getting married to this girl. She wasn't bad looking. Chocolate colouring, quite small and curvy, and she had a wide, friendly face, like the face of a sun. The kind of face that would maybe light up when she was happy. On this point, of course, I was only speculating -- she looked pretty serious at that moment, you'd have thought she was at a funeral. I was glad she was attractive. I wouldn't have wanted to marry just any old muffin. That was a fucked-up way to think, I know, but that was what I was thinking as I stood and sweated in a borrowed suit. She had this long brown-and-green wraparound dress on, a headscarf in the same stuff and a bunch of wooden jewellery like you see white college girls wearing. She was Nigerian, she was called Femi. I didn't know much else. I reckoned she must have been about my age: twenty-five. The registrar, a short, bald white guy, spoke in solemn tones, 'Solomon Thomas, do you take this woman to be your lawful wife?' It didn't feel like he was talking about me. For a start, no-one called me Solomon. It was Sol. The surname never really felt like me, either. It was all I ever got off my father. Not a bad man, my mother said, but very unreliable; he cleared off back to the yard soon as I was born. my mum went back five years ago. She saw him once, on the other side of the street. She didn't cross it. Why, suddenly, had my parents come to mind? 'I do,' I said. She said she did, too, and we did the thing with the rings. They were also borrowed. In 2008, a decade after Go, Lewis brought out Bad Traffic, a novel about Chinese who end up in Britain by various routes, including human smuggling, and have the usual (and some unusual) difficulties. Originally published in the UK as a paperback, this second work quickly appeared in the US in hardcover and paperback editions, and in Swedish, German, Italian, and French translations, and Japanese and Turkish translations are scheduled for 2010. |

||||

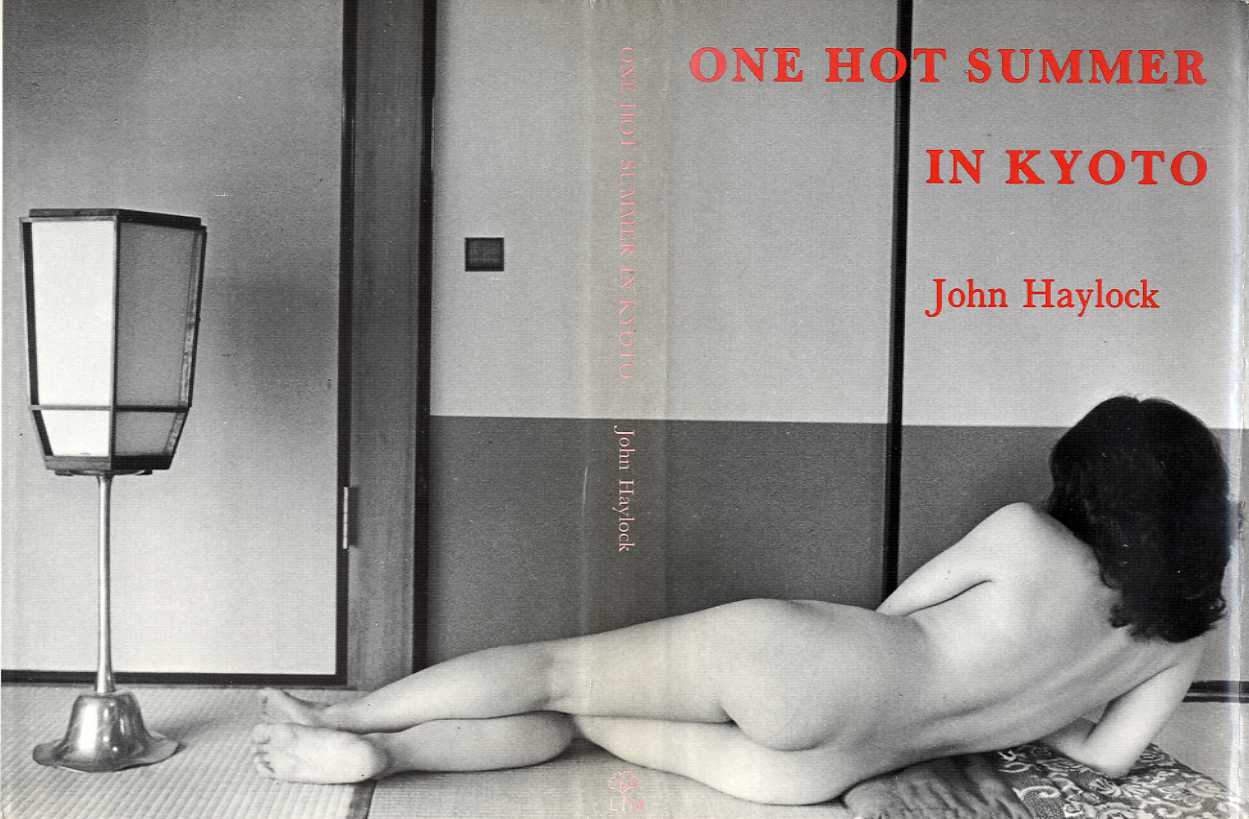

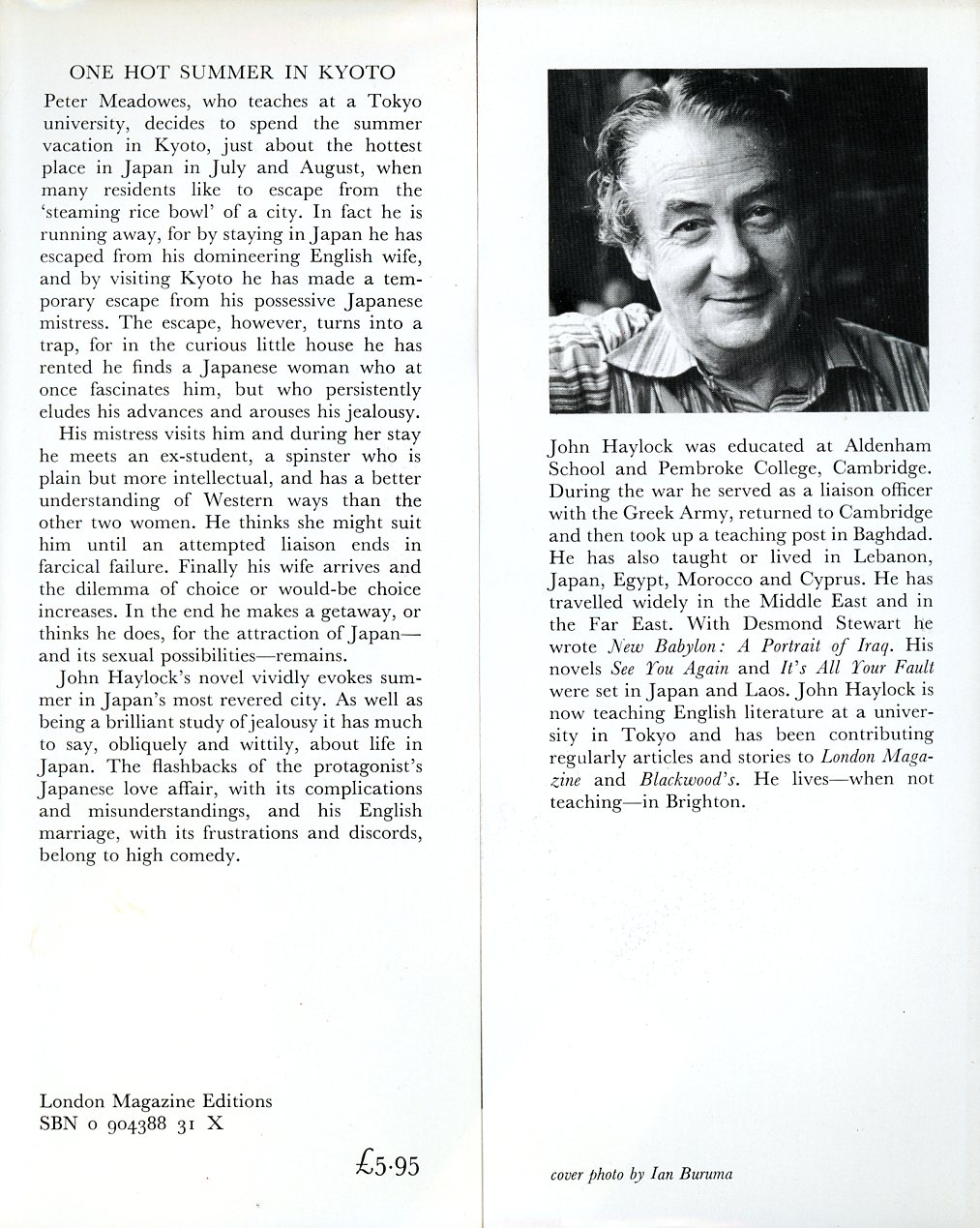

John Haylock 1980One Hot Summer in KyotoJohn Haylock John Haylock (1918-2006) was born in Bournemouth in Hampshire and died in Brighton in East Sussex, but travelled and lived in several countries, most significantly in post-Pacific War Japan. His earliest novels, including One Hot Day in Kyoto, featured mainly heterosexaul characters, but his later stories concerned mostly homosexual and bi-sexual men. One Hot Summer in Kyoto tells the story of Peter Meadowes, a teacher in Tokyo, who came to Japan to escape from Monica, his domineering English wife, and his daughter in elementary school, who he barely knows. One summer, he vacations in Kyoto to get away from Noriko, his is possessive and jealous Japanese mistress. In Kyoto he starts a relationship with Kazumi. She is mistress of Oliver, who is away at the time and has let Meadowes stay at his home. Kazumi had been a main at Oliver's house when Oliver's house and continued living there after Oliver's wife was killed by a truck. Kazumi, who feels obliged to look after the house and Meadowes while he is there, initially resists his approaches but eventually is drawn into his embrace. In the meantime, Meadowes runs into Miss Goto, an older never-married ex-student who seems to understand "western ways" better than the other women in his life, including his English wife. Miss Goto professes her love for him. Their awkward affair fails, but she lingers around to be in his aura. Noriko then comes to Kyoto to make sure Meadowes is behaving himself. When she and Kazumi and Miss Goto are eating together with their mutual lover, Noriko signals that she and Meadowes are more than friends. Then Monica decides to visit Japan. The story is told with Haylock's reputed sense of humor about relationships between foreign (especially British and American) men in Japan with Japanese women -- and between such foreign men and Japan itself, which provokes both love and hate in many. Haylock's writingsOne Hot Summer in Kyoto was the 3rd of Haylock's several novels and non-fiction works. He appears to have written the story while in Japan in the 1970s. After retiring a few years later, he began cranking out many more books while dividing his time between Japan, England, and Thailand. The following list does not include a couple of translations of French works, co-authored titles, and magazine stories and articles.

1963 See You Again Chapman and Hall

[An Englishman working as a teacher in Japan in the

1960s deals with the relationship between Margery,

an English ballerina, and her Japanese pupil Taizo]

1964 It's All Your Fault Chapman and Hall

1979 Choice And Other Stories Eichosha New Current Novels

1980 Tokyo Sketchbook Yumi Press

[Travel guide]

1980 One Hot Summer in Kyoto London Magazine Editions

1987 Japanese Memories

1990 A Touch of the Orient Peter Owen

[Dust jacket blurb]

in which nothing is quite what it seems

including all notions of sex . . .

1993 Uneasy Relations Peter Owen

[Japanese title on dust jacket]

不安な関係 ジョン ヘイロック

[Dust jacket blurb]

An explicit novel set in Japan today

[Divorcee Sylvia Field takes a teaching job in Japan.

Gay friends introduce her to Tokyo night life,

including host clubs for frustrated housewives.

Then her gay son visits Japan with his lover.]

1998 Doubtful Partners Arcadia Books

[Muscular Asian man on cover]

[Cover promotion]

If there is one thing to bring out

the candid in Haylock it is

the ins and outs of intimate intercourse

-- The Times

[Barbara Lane travels from England to Thailand to settle

husband's affairs and discovers he had a male lover.]

1999 Body of Contention Arcadia Books

[1960s Tangier, a run-down Hotel Ritz,

and its assorment of eccentric expats]

2003 Loose Connections (2004) Arcadia Books

[Cover promomotion]

'Highly diverting'

-- Peter Burton, Gay Times

2004 Eastern Exchange Arcadia Books

Memoirs of People and Places

2006 Sex Gets in the Way Arcadia Books

[Two tattooed merchant marines on cover]

[Cover promotion]

If there is one thing to bring out

the candid in Haylock it is

the ins and outs of intimate intercourse

-- The Times

Though novels and other writings should not be taken as reflections of an author's personal experiences, tastes, or beliefs, it is not unreasonable to ask to what extent an author's choice of subject matter, and execution of a story, project his or her fantasies or misgivings about life. For writing a story can be as much an escape from reality for an author, as reading the story may be for a reader. The most available edition of One Hot Summer in Kyoto, with an ironic cover blurb by Donald Richie, was brought out by Stone Bridge Press in 1993. Stone Bridge Press has also posted on its website a substantial biographical sketch of John Haylock by the gay journalist Peter Burton (1945-2011), who examines Haylock's real and fictional lives as "a survivor from a generation of well-off gay men who made their lives abroad because when they were young Britain was inhospitable and when they were old it was incomprehensible." |

||||||

Dianne Highbridge 1999In the Empire of DreamsDianne Highbridge Forthcoming. |

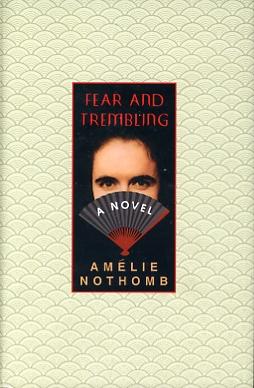

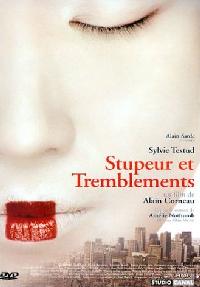

Amelie Nothcomb 1999, 2000, 2001Stupeur et tremblementsOsore ononoiteFear and TremblingFrench editionsAmelie Nothomb Paris: Editions Albin Michel S.A., 1999 Paris: Hachette, 2001 Japanese editionAmerii Nooton English editionsAmelie Nothomb New York: St. Martin's Press, 2001 New York: Griffin (St. Martin's Press), 2002 New York: Griffin (St. Martin's Press), 2004 London: Faber and Faber, 2004 Belgian born in JapanThe woman with the thick brows, clinging to a dress and hiding behind a mask, is Amelie Nothomb. The back flap of the jacket of the first US edition introduces her as follows. Belgian by nationality, Amelie Nothomb was born in Kobe, Japan, and currently lives in Paris. She is the author of eight novels, translated into fourteen languages. Fear and Trembling won the Grand Prix of the Academie Francaise and the Prix Interenet du Livre. Nothomb's father is the Belgian diplomat Baron Patrick Nothomb, who has been the Ambassador of Belgian to Japan, China, and the United States. This makes her the niece of Charles-Ferdinand Nothomb, Belgian's Foreign Minister from 1980 to 1981. Nothomb was born in Kobe in 1967 and lived in Japan for five years while her father was serving there. She went on to China, New York, Bangladesh, Burma, and Laos before, at age 17, she began living in Belgium. She returned to Japan around 1990 to work, possibly at Sumitomo, apparently as an interpretor. She then went back to Europe, and published her first novel, Hygiene de l'assassin [The health of a murderer], in 1992. It became a bestseller and was translated into Japanese as Satsujinsha no kenkoho (Bungei Shunju, 1996). Amelie's move back to Europe, and her debut as a writer, are alluded to at the end of Stupeur et tremblements, her first autobiographical novel. She is very popular in France and Belgium, where she has published nearly twenty novels and counting. Half a dozen of them have been translated into English, and three have appeared in Japanese. Ancient Japanese protocolThe front flap introduces the story. According to ancient Japanese protocol, foreigners deigning to approach the emperor were to adopt a tone of fear and trembling. Terror and self-abasement conveyed respect. Amelie, our well-intentioned and eager young Western heroine in this new novel by Amelie Nothomb, goes to Japan to spend a year working at the Yumimoto Corporation. Returning to the land where she was born is the fulfillment of a dream for Amelie; working there turns into comic nightmare. Poor Amelie can do nothing right. She starts at the bottom of the corporate ladder and immediately reveals a genius for working her way down. She delivers mail, serves tea, updates calendars, photocopies the same pages a thousand times; her job description, fluid at best, runs relentlessly downstream. But of Amelie's many failings and ill-advised breaches of protocol, the worst by far is becoming infatuated with her immediate superior, the beautiful, impeccable, and implacable Miss Mori. Hailed by critics in France, where it won a number of prestigious awards and was a bestseller, Fear and Trembling is alternately disturbing and hilarious, unbelievable and shatteringly convincing. At its core lies a clash of wills and war of nerves that will keep readers clutching tight to the pages of this taut little novel, caught in the throes of fear, trembling, and, ultimately, delight. Miss MoriAmelie took orders from everyone in the import-export division of the Yumimoto Corporation (page 1). Why the company is called this is later explained (page 5). Whenever I think of Fubuki Mori, I see the Japanese longbow, taller than a man. That's why I have decided to call the company "Yumimoto," which means "pertaining to the bow." And whenever I see a bow, I think of Fubuki. The reader is then introduced to Miss Mori, her supervisor, who across from her (page 5). "Miss Mori?" "Please, call me Fubuki." Miss Mori was at least five feet ten, a height few Japanese men achieved. She was ravishingly svelte and graceful despite the stiffness to which she, like all Japanese women, had to sacrifice herself. But what transfixed me was the splendor of her face. So many of the "conflicts" in the story are so implausible that one wonders why it received so much praise in France. On second thought, people on both sides of the Atlantic are known for their capacity to believe whatever they like about Japan. Feelings of trustAn early example of the novel's silliness -- notwithstanding Nothomb's intent to be funny -- is a scene where Amelie is ordered by Mister Saito, who is Miss Mori's senior, to serve coffee to an important delegation of twenty visitors in the office of Mister Omochi, who is Saito's senior. Later Amelie hears Omochi thundering Mister Saito's name and then scolding him. Mister Saito then furiously called for her and she follows him to an empty office. He is so angry he stammers (pages 11-12). "You have thoroughly antagonized the delegation from our sister company! You served the coffee using phrases that suggested you speak Japanese absolutely perfectly!" "I don't speak it all that badly, Saito-san." "Be quiet! Why do you believe you can defend yourself? Mister Omochi is very angry. You created the most appalling tension in the meeting this morning. How could our business partners have any feeling of trust in the presence of a white girl who understood their language? From now on you will no longer speak Japanese." I was dumbfounded. "I beg your pardon?" "You no longer know how to speak Japanese. Is this clear?" "But -- it was because of my knowledge of your language that I was hired by Yumimoto!" "That doesn't matter. I am ordering you not to understand Japanese anymore." "That's impossible. No one could obey an order like that." "There is always a means of obeying. That's what Western brains need to understand." Now, we're getting to it, I thought. "Perhaps the Japanese brain is capable of forcing itself to forget a language. The Western brain doesn't have that facility." This absurd argument seemed admissible to Mister Saito. "Try all the same. Pretend. I have been given orders. Do you understand?" SnowstormAmelie tells Miss Mori she hates Mister Saito and regards him as a bastard and an idiot. Miss Mori tells her to calm down, and then defends him, Mister Omochi, and the president Mister Haneda, to whom Amelie had thought she might complain. Amelie tells Miss Mori she's her only hope, thanks her for her kindness, then changes the conversation to her name (page 15). I asked her what the ideogram of her first name was. She showed me her business card. I looked at the kanji. "A snowstorm!" I exclaimed. "'Fubuki' means 'snowstorm'! I can't believe anyone's actually called that." "I was born during a snowstorm. My parents saw it as an omen." Amelie recalls the precise date that Miss Mori was born in Nara, and tells her she is glad they were both "daughters of Kansai . . . where the heart of the old Japan still beats." To the reader, at least, she then discloses this about her own past (page 16). I was five years old when we left the Japanese mountains for the Chinese desert. That first exile made such a deep impression on me that I had felt I would do anything to return to the country that for so long I thought of as my native land. Maladjusted parodyFear and Trembling is mercifully short. With barely 250 words on each of its 132 pages in English translation, is over before most bloated paperback thrillers clear the runway. While utter nonsense as a mirror of working conditions in an actual Japanese company for any foreigner as fluent in Japanese as Amelie, the protagonist in the novel, it can be swiftly read as a farce and as such relieve a lot of stress. Apart from the warped sociology in the story, the reason the novel doesn't work is that anyone who had become as fluent as Amelie in Japanese would, by the time of their employment in a Japanese company, have learned enough about what to expect in Japan that they would not have have reacted to any situation the way Amelie did. Ultimately, Nothomb has told another version of the familiar story about a foreigner who either couldn't adjust, or who didn't want to. French-Japanese movieA movie version of Nothomb's novel was released as "Stupeur et tremblements" in 2003. Directed by Alain Corneau, who also wrote the scenario, the movie features Sylvie Testud as Amelie, Kaori Tsuji as Fubuki (Mademoiselle Mori), Taro Suwa as Monsieur Saito, Bison Katayama as Monsieur Omochi, Yasunari Kondo as Monsieur Tenshi, Sokyu Fujita as Monsieur Haneda, and Gen Shimaoka as Monsieur Unaji. The film is in French and Japanese, but DVDs with English subtitles have been released in the US and UK. Same old preconceptionsHow is the movie seen in the United States? If G. Allen Johnson's review in the "San Francisco Chronicle" (5 August 2005) is any indication, it's just another example of Europeans and Americans convincing themselves that it is impossible for them to understand Japan -- an old and sad preconception (see SFGate.com for complete review). Fubuki's enigmatic behavior is the key to [director] Corneau's point about the ultimate unknowable nature of the East to Westerners. Japan's class structure works (for the Japanese anyway) in a business environment, but can be tough for a Westerner to crack. [ . . . ] "Fear and Trembling" is the best office comedy since "Office Space" and the best examination of East-meets-West corporate clashing since the underrated Ron Howard/Michael Keaton movie "Gung Ho" 20 years ago. What can one expect from a reviewer who thinks "Gung Ho" is underrated? Come to think of it, it is -- as another Hollywood exercise in stereotyping disguised as "cultural clash" humor. |

||||||||||||||

Susanna Quinn 2012Glass GeishasSusanna Quinn Forthcoming |

||||

Emily Barr 2001BackpackEmily Barr Forthcoming. |

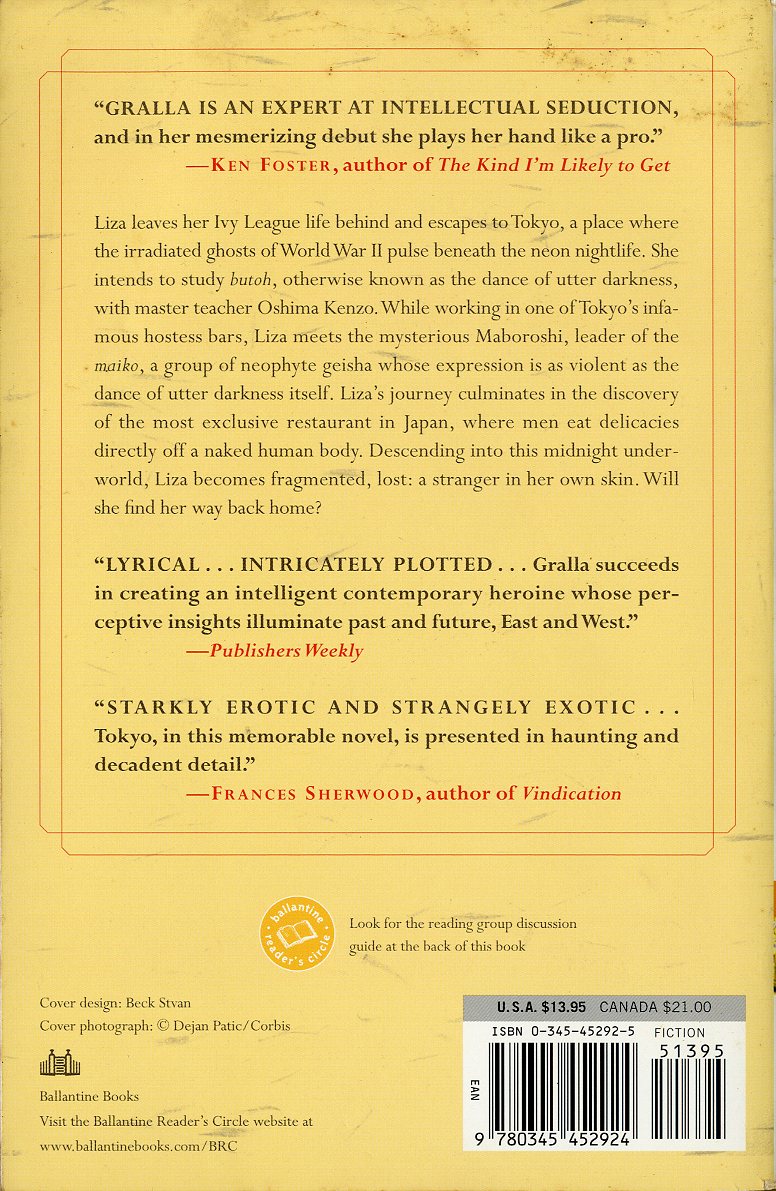

Cynthia Gralla 2003The Floating WorldCynthia Gralla Author blurbCynthia Gralla is a Ph.D. student in comparative literature at the University of California at Berkeley. She has written about her experiences living and working as a hostess during visits to Japan for salon.com. She lives in San Francisco with her husband, Michael. |

||||

John Christopher Harris 2001The BackpackerJohn Christopher Harris Some never come backThe back cover blurb does a good job inviting the browser to plunge in from page one. 'Leaving the blinding sand for the cool shade of the trees, I walked carefully through the undergrowth to where Dave, using two twigs as chopsticks, was picking up a freshly severed human finger . . .' John's three-week holiday in India starts badly. After his girlfriend falls ill with a severe case of 'Delhi belly' and returns home alone, he finds himself looking at the sharp end of a knife in a train station latrine. But such is the stuff of backpacking and his life is saved -- and turned upside down -- by Rick, an enigmatic, streetwise traveller, who persuades John to throw a future of mundane security to the wind and embark upon a series of increasingly bizarre journeys. On the island of Koh Pha-Ngan, John, Rick and Dave pose as millionaire aristocrats in a hedonistic Eden of beautiful girls, free drugs and wild beach parties. However, their new world comes crashing down around their ears and they find themselves enbroiled in the politics of the Thai Mafia. With retribution hot on their heels, they head for Bali, but tragedy strikes and sees them ricocheting through Indonesia, Australia and Hong Kong. This is not travel for the faint-hearted: some backpackers never return. To be continued. |

Sarah Bird 2001The Yokota Officers ClubSarah Bird Sarah Bird Okinawa base lifeThe journalistic style of the back cover blurb echoes the prosaic tone of the novel itself. After a year away at college, military brat Bernadette Root has come "home" to Kadena Air Base in Okinawa, Japan, to spend the summer with her bizarre yet comforting clan. Ruled by a strict, regimented Air Force Major father, but grounded in their mother's particular brand of humor, Bernie's family was destined for military greatness during the glory days of the mid-'50s. But in Base life, where an unkempt lawn is cause for reassignment, one fateful misstep changed the Roots' world forever. Yet the family's silence cannot keep the wounds of the past from reemerging nor can the memory fade of beloved Fumiko, the family's former maid, whose name is now verboten. And the secrets long ago covered up in classic military style -- through elimination and denial -- are now forcing their way to the surface for a return engagement. The blurb is wrong about the status of Okinawa, at least at the time of Bird's story. It is set before 1972, when Okinawa was returned to Japan. In the story, Okinawa was not part of Japan but was under US administration. This is made very clear from the opening, which features this letter (page 3).

Yokota Air Base was then and still is in Tachikawa, near Tokyo, in Japan then and now. In action at Luigi's Pizza in Tokyo, Bobby, involved underworld activities in Okinawa, is trying to do business in Tokyo, and Lou, the proprietor, aware of four yakuza glaring at Bobby from a corner, advises Bobby that he's in a different world. "Bobby, you can't do business here." "What 's the problem?" "It's different now. You been gone for a while." "Lou, you can't let them run your game, man. You can't do this." "Shut up, Bobby. You're over there in Okinawa, you don't know how it is here now. Okinawa is America. You're in Japan now." |

|||||

Sara BackerAmerican FujiSara Backer The blurb on the back reveals this much of the plot. Gaby Stanton, an American professor living in Japan, has lost her job teaching English at Shizuyama University. (No one will tell her exactly why.) Alex Thorn, an American psychologist, is mourning his son, a Shizuyama exchange student killed in an accident. (No one will tell him exactly how.) Alex has come to this utterly foreign place to find the truth, and now Gaby -- newly employed at a Japanese "fantasy funeral" company -- is his guide. Gaby, at least, can speak the language, though as she explains to Alex, the key to mastering Japanese is understanding what's not being said. And in this dazzling, unusual novel, the unsaid truths about everything from work to love to illness and death cast a deafening silence -- and tower in the background like Mount Fuji itself. The narrative is fairly well-paced but the story doesn't live up the hype. Alex is a bit of a jerk, and even Gaby fails to inspire much sympathy. Growing ideasBacker makes the following comment in a web interview. If I hadn't lived three years in Japan, I could never have written this novel. While the characters and events are imaginary, the Japan I describe is the one I experienced. And my story couldn't happen anywhere else; it's not like I "set" it in Japan, but rather that the premise and ideas grew out of that unique and amazing culture. Backer taught English at Shizuoka University. Possibly because she lived in Japan only three years instead of one or thirty, she spoiled the narrative with language lessons. The story brings together a variety of English-speaking foreigner and mostly English-speaking Japanese personality types, types foreign and Japanese compartmentalized involves several sojourners and several kinds of Japanese, explores several kinds of personalities sojourners and Japanese, novel is also weakened by the sort of self-conscious commentary on Japan that mars most sojourner fiction. Some elements of the plot -- like heart transplants, which were very controversial at the time Backer was in Japan and continue to be unusual -- are most growths in Backer's brain, rather than tumors of experience in Japan. Gaby's fateBacker denies that she is Gaby. Japan is a hierarchical society. As such, ALL of my experiences in Japan were shaped by the fact that I was a woman, a foreigner, and a university professor, an extremely rare combination. While I'm not like Gaby emotionally or temperamentally, her take on Japan is the same as mine -- not representative of "The American Experience," certainly at odds with the impressions of American men, but completely authentic. This much may be true. For Backer left Japan, while Gaby decided to stay. Though the story begins with Gaby, it ends with Alex, as he climbs Mt. Fuji and meets the man who received his son's heart. Throughout the story, the man thinks the heart came from a Korean, but this thread -- like many others -- leads nowhere and is left dangling. |

Katy Gardner 2002Losing GemmaKaty Gardner Forthcoming. |

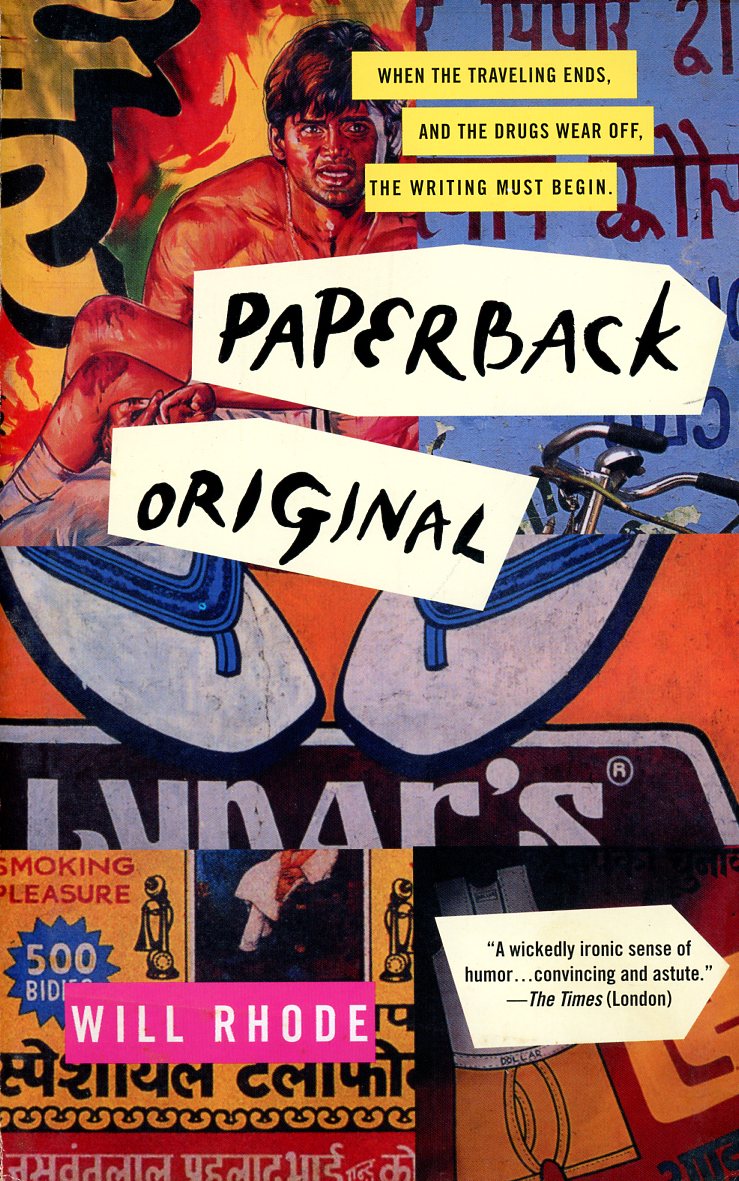

Will RhodePaperback OriginalWill Rhode Will Rhode, aka William Rhode . . . Forthcoming. |

||||

Hari KunzruTransmissionHari Kunzru Forthcoming. |

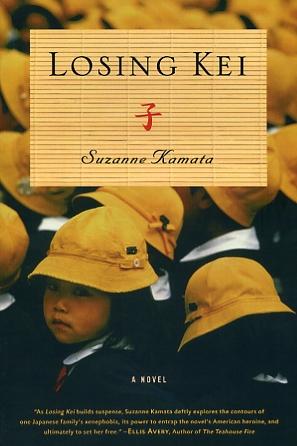

Suzanne KamataLosing KeiSuzanne Kamata This is not a bad story -- but the quality of its narration is uneven -- and its plot would have been better served by making the protagonist and the two anti-protagonists more credible. Jill Parker, the heroine, should have been more sympathetic. And the rather plastic figures of her lover, then husband, then ex -- and her temporary mother-in-law -- could have been molded, textured, and painted to appear more human. The most honest character in the book may be the Filipina club hostess. Little is said about her, yet the impression is left that she will find happiness because, despite the instrumental quality of her survivalist life in Japan, she seems to know the name of the game -- and how, in her own way, to win. More is shown and told about Parker's American surfer friend. He, too, though a recognizable caricature, comes across as someone who -- inspite (or because) of his quirkiness -- will survive on his own terms. One is not so sure about Jill Parker. The ending appears to be happy -- but, by then, the reader has probably concluded that she is too narcissistic to ever be happy -- too apt to sulk and hit the bottle, or otherwise destroy herself, if things don't go her way. There is no shortage of such people in this world. And arguably the United States, Japan, and a number of other countries have busily been producing more men and women whose thresholds of happiness are too self-centered to tolerate marriage. Parental fights and rightsI do not, however, get the impression that Kamata intended Jill Parker to have such faults. Rather I think she succumbed to the common temptation of plotting a novel around a contemporary "social issue" -- in this case, "child abduction" by Japanese spouses or ex-spouses of aliens. In typical cases -- including the few I have had occasion to know about as a friend, friend of a friend, or referred amateur counselor -- the Japanese woman "abducts" the child or children she has had in a marriage with an American or British man she leaves for better or worse. Cases involving "abduction" by a Japanese father are comparatively rare -- and even in Japanese-Japanese divorces are, today, unusual. Disclosure In most cases that I have personally known about through approaches from one of the spouses, usually the non-Japanese spouse, I have sympathized more with the Japanese spouse -- while realizing that, in all tugs of war involving children, the ultimate "losers" are the children. Kamata's novel is interesting as a "case" involving an American woman who would appear to have no choice but to abandon her child without American-style court mediated visitation rights -- to say nothing of alimony and child support. The reader, though, is left with nothing but stereotypes about the way statutes and customary law might actually work in Japanese courts -- to say nothing of the kinds of agreements that are likely to be reached privately, without the intervention of an attorney. Kamata takes the easy way out. She contrives a connection between Parker's ex and yakuza. And sure enough, a yakuza persuades Parker to back off with her American demands for parental rights if not custody. This, of course, lets Kamata off the hook. For thanks to the yakuza, she is no longer obliged to examine the real world on either side of the Pacific. To do so would have turned the story into a boring legal drama. The better alternative would have been to write a true novel -- rather than a polemic on the putative enigma's of Japanese culture and cultural friction. "Enigmatic culture"The blurb on the back cover baits the reader like this.

The blurb reads very much like a pitch for using the book in an undergraduate course on "intercultural marriage" at an American university, or in an American-style "multicultural" course at a college in Japan. I have actually, in good faith, recommended the book to a professor who is teaching such a course at a certain institution of higher learning in Tokyo. Fortunately, he or his students will have to come up with their own discussion questions. Unlike novels that are aimed at "multicultural" niche markets, Losing Kei lacks the didactic aids that increasing come at the end of books published in the United States. Meaning that it is not such a work -- though one would never know this from its cover blurb. |

Angela Carter 1970-1974Oriental Romances -- JapanAngela Carter The English author Angela Carter (1940-1992) was known for her novels, short stories, poems, and journalism. "Oriental Romances -- Japan", first published in New Society in 1974, reports a trip she made to Japan in 1969 to spend some money she was given "to run away with" -- money that came with the Somerset Maugham Travel Award. It was enough take her to Tokyo, not much further, so she stayed in Tokyo for a while, "making a living one way and another including working in a bar". Her report, as collected in Nothing Sacred in 1982, includes 5 chapters -- Tokyo Pastoral, People as Pictures, Once More into the Mangle, Poor Butterfly, and A Fertility Festival. Slave or toyCarter relates an account by an English teacher of English who asked a student "What is the quality that you would require in a wife?" The student -- a lawyer who had graduated from a top university -- replied: "Slavery. I can get everything else I need from bar hostesses" (page 44). Carter opined that women in Japan are denied opportunity to express their "true femininity" and have but two choices -- to be a slave or a toy. And she would find herself in the midst of the "battle of the sexes" when she accepted a job to work a few shifts as a hostess in a bar named "Butterfly" (page 45). Carter describes the bar in Tokyo's Ginza district and the exotic and sometimes skimpy clothing worn by it's 15 regular hostess -- who, unlike the Carter and a few other foreigners that were hired to work for 5 nights on 2-1/2-hour shifts -- worked all the time. Then she describes the hostesses (page 46). [T]he hostesses were lumpy girls, on the whole, and, as they say about race-horses, aged. The mama-san, a kimono'd pouter pigeon, had the slightly harassed, professional joviality of a woman who has not yet put enough by for her old age -- though her place, handsomely subsidised as it was by the Japanese government via the expense account system, was very plainly coining it. American sojourners can't write this way. To be a woman and radicalizedIn her introduction to "Oriental Romances -- Japan", Carter writes that she wrote the first 4 stories during the 2 years she lived in Japan "in the early 1970s, when Japan was just starting to boom". She returned for a holiday in 1974, and went to the festival described in the 5th story. She reportedly went to Japan to get away from her first husband. She went to Japan "to live for a while in a culture that is not now nor has ever been a Judaeo-Christian one, to see what it was like." Apparently she saw what it was like -- and "In Japan," she writes, "I learnt what it is to be a woman and became radicalised" (page 28). |

||||||

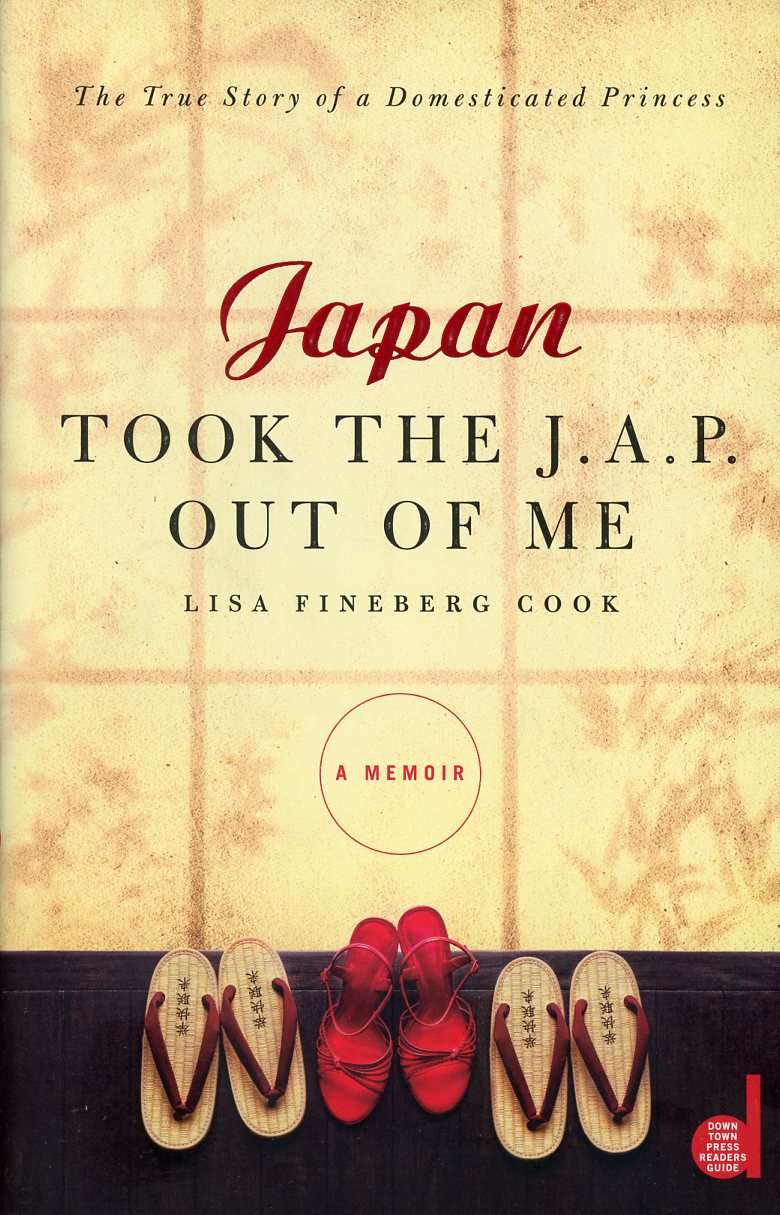

Lisa Fineberg Cook 2009Japan Took the J.A.P. Out of MeLisa Fineberg Cook The author has fun relating how her stay in Japan, starting in lieu of a honeymoon immediately after her wedding in Los Angeles, where she had been raised in the mold of an archetypal Jewish American Princess, is forced to live on Japan time. For the first time in her pampered life, Cook had do her own laundry without an automatic washing machine and drier, using an ordinary contemporary Japanese model -- washing and rinsing a few times in one small tub, spinning in another, and hanging everything out on a clothesline strung across the tiny veranda of an apartment that was more like a walk-in closet for her. Her L.A. shopping habits, characterized as those of a "Retail Queen", also changed, partly because she was pregnant and had to prepare for motherhood -- which which helped take the P. out of the J.A.P. in her. She clearly remained an A. It's not clear what became of the J., if ever it was there. The biggest shock for her was to be noticed -- looked at -- studied -- stared down -- everywhere she went -- a blonde girl in a sea of black. Anti-Semitic movementCook unfolds her life in Japan in 6 chapters -- Laundry, Cooking, Transportation, Shopping, Cleaning, Intermission -- each with a decorative Japanese title -- 洗濯、料理、交通手段、買い物、掃除、休憩. The narrative is not as compartmentalized as the chapterization would make it seem. While every chapter is full of anecdotes related especially to its subject, the other subjects are in the background. And all subjects are interlaced with a long list of other themes, like marriage, language, work, culture, pregnancy, working, pregnancy -- even religion, or ethnicity or race, whatever it means to be Jewish. The "Transportation" chapter includes the following exchange between Lisa Cook and another "Caucasian" English teacher who Cook thinks at first is an American but turns out to be a Canadian (page 138). She has no accent, but I notice that she has a huge chest. Thank God! Someone is bigger than me. "Nice to meet you. Are you American?" "No. Canadian." "Oh! Were you back in Canada last week?" "No, my fiancé and I were in Israel." "Israel! No way. Did you love it?" "We do love it. I'd been there before with him. We go for his business." "What's his business?" "He is working on denouncing the anti-Semitic movement that has sprung up here in Japan." I am not sure I heard her correctly. "Excuse me? Did you say anti-Semitic movement here?" "Yes, a fairly large underground movement, actually." I don't know what to say. "I didn't realize that Japan had a large Jewish population." "It doesn't, and I guess they're trying to keep it that way." "Are either of you Jewish?" "No. In fact, he's Japanese. It's just something he's become very passionate about in the last few years." My mind flashes to the downtown vans. I knew it! God, a Jewish foreign women -- I'm like a walking poster version of everything these people hold in contempt. The "downtown vans" allude to some black vans she'd seen downtown, earlier in the chapter, with darkened windshields and red "quasi-swastikas" boldly painted on their doors, and a rooftop megaphone blasting with "the strident voice of a presumably young fascist" (pages 89-90). In the course of her story, Cook trots out a number of social issues but stays a comfortable underinformed or misinformed distance from them, preferring a quicker and lighter narrative about something other than herself. The novelistic biography is followed by a 3-page interview titled "Up close and personal with the author", in which the reader learns that Cook doesn't keep in touch with her Japanese friends or students because "Sadly . . . things got lost -- including my address book with the names and numbers of my Japanese contacts." Cook loses a lot more about life in Japan than she finds, which is probably inevitable hence normal in the case of aliens who come to Japan for a few years, but leave before they realize they are not just in Japan but of Japan. Which is not to say that staying in the country longer, under more native conditions not buffered by bilingual intermediaries, would have made her feel more at home. It is possible to have been born in a country, be a native speaker of the dominant language and navigate daily life as reflexively as one breathes air, and feel somehow alienated by one's situation and station in life. Cook doesn't need to become a part of Japan. All she needs to do is survive her initial reactions to conditions that are entirely unexpected, new, and discomforting. But character trumps discomfort. Her personality compels her to accept her new conditions with a sense of humor -- which is probably the most essential quality to have when crossing borders between the familiar and unfamiliar. Writing about one's sojourner experiences as Cook has, or through a novel, is therapeutic. Reading such writings is also therapeutic, whether one has been to Japan or plans to go -- or, like this reviewer, has spent most of his life in Japan and adopted it as his home. |

||||