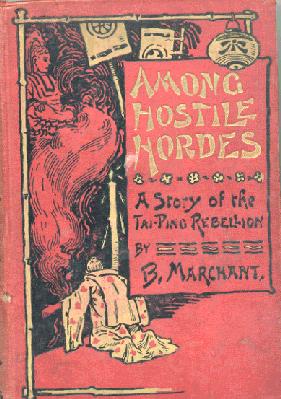

The Steamy East (4)The "Fragrant Port"By Mark SchreiberMainichi Daily News Around 1901, Bessie Marchant, a prolific British author of children's fiction, penned Among Hostile Hordes, a Chinese historical adventure set during the Taiping Rebellion. Although the East India Company was licensed in 1609 by the British crown to trade as a monopoly in the Far East, the only Europeans to meet with any initial success were the Portuguese in the south and the Russians in the north; it was not until 1699 that the first English ship was allowed to trade at Canton. The opening up of Canton for large-scale trade to ships of all nations came after two centuries of delaying action on the part of Chinese. Nevertheless, restrictions abounded: Foreign "factories" (warehouses) were confined to a small ghetto outside the city walls, where they made their purchases, of tea, silk cloth, ginger, sugar, rhubarb and other items. While business was profitable, Life was indeed hard in those times. Luxuries were few, with such maladies as scurvy and dysentery a constant threat. The notion of "non-tariff barriers" may indeed be a Chinese invention, for in addition to complex red tape, and customs duties for the. exchange of goods, Chinese officials demanded their "squeeze" - bribe - for virtually every type of transaction. As a way of reducing their trade deficit, foreign merchants found a ready market in China for India-grown opium. Indeed, the drug became such a problem that in 1729 it was banned by imperial edict; but the combination of rampant smuggling and official corruption failed to blunt its spread. While foreign privateers sailed up and down its coast in increasing numbers, China, the "Central Flowery Kingdom," remained blissfully unconcerned with the state of the world beyond its borders. The British, who had established their supremacy on the seas, began to get just a wee bit impatient over the arrogance shown by the Imperial Chinese government. The first British mission journeyed to Peking in 1793, "bearing gifts for the Emperor of China from the King of Great Britain." Unimpressed, the aging Emperor Ch'ien Lung replied thus to King George III: Now you, 0 King, have presented various objects to the throne, and mindful of your loyalty we have specially ordered our Ministry to receive them. Nevertheless, we have never valued ingenious articles, nor do we have the slightest need of your Country's manufacture... After a change of emperors, Lord Amherst tried again 23 years later, only to be turned away more abruptly, with "Your presents are of no interest or use. In the future, do not bother to dispatch them." Needless to, say, the British found this attitude infuriating, and things started getting nasty - especially when the Chime adopted draconian measures to deal with the opium problem. By 1838, imports of the drug had quadrupled from only a decade before, and the confiscations, burnings and arrests escalated into a military conflict that culminated in the first Opium War in 1839. Victorious, the British won access to Shanghai, Ningpo, Amoy and two other "Treaty Ports," as well as perpetual title to a rocky, 30-square-mile island, 80 miles from Canton: Hong Kong. The British took title on January 25, 1841. Not everyone back in England found the victory over the Chinese an occasion for celebration. In Parliament, William Gladstone, who was later to become prime minister, expressed, his outrage at the actions of the navy:

Once they had their own colony, the next step by the British was to declare Hong Kong a free port; Chinese merchants from neighboring provinces flocked to the new British territory if for no other reason than to escape from the corruption rampant in their own country. Foreign trading firms headed by partners or managers - called taipans - and their assistants - the griffins - engaged in spirited competitions. Most of these oldtime taipans were rarely over thirty years old. Probably the most exhaustive historical work on the circum stances that led to the founding of Hong Kong is J. B. Eames) The English in China, a massive book first published in 1909 and reprinted in 1974. In fiction, James Clavell's 1966 novel Taipan stands as the definitive work on Hong Kong's early years, and as such must be regarded as compulsory reading. The story begins Jan. 26, 1841 - the day after the founding of the colony. The Taipan is Dirk Struan, a Scottish sea captain and opium trader who struggles against cutthroat business rivals, members of his own family, Chinese pirates and Mother Nature to found a great commercial dynasty - Struan and Company, also known as the Noble House. Like Shogun, Clavell's other bestseller, Taipan, also overflows with a tragic romance, in this case between Struan and a beautiful Chinese concubine, May-may. A blockbuster adventure story with a cliff-hanger ending to every chapter, it is due to make its Hollywood premiere in a matter of months, and I for one look forward with interest to see how this unforgettable tale of Hong Kong's early days makes the transition to the silver screen. |

www.wetherall.org