The House of 'Rising Sun'

Deceit and betrayal: old grist for new mill

By Mark Schreiber

A version of this review appeared with William Wetherall's

"Crichton's fiction merges realism, revisionism and racialism" in

The Japan Times, 12 August 1992, page 17 (Focus)

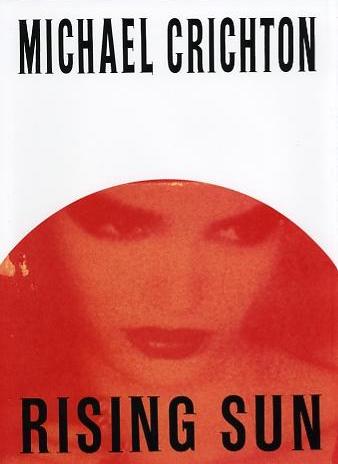

Michael Crichton Four months before the appearance of Michael Crichton's novel Rising Sun in February, I spoke before the Popular Culture Association of Japan on "The Coming War with Japan as Portrayed in Contemporary U.S. Fiction." I based my presentation on over two dozen works of American popular fiction that anticipated an outbreak of conflict (including technological and other nonmilitary conflict) between Japan and the United States. I noted that such stories, especially the more recent ones, tend to echo ever more closely the political and economic problems identified as "economic friction" by the news media. From the novels about Japan churned out over the past several decades, one might conclude that the vast majority of America's fiction writers slept through the entire U.S. Japan peace conference back in 1952. Their works, I noted, had many features in common, including these three: Japanese "aggression" against the U.S. is characterized subterfuge and stealth. In this sense, the stories continue to perpetuate the World War II-era notion of the "sneaky" Japanese. Japan's demographic and social problems tend to be glossed over or ignored, giving it an exaggerated image of power. It is common for such books to echo American concerns, e.g., the "money game" on Wall Street, the decline of the manufacturing sector, and social problems including racial conflict, drugs, violent crime, and so on. It is no coincidence that the above features also figure in Rising Sun. Michael Crichton's book, in fact, pretty much holds to the pattern established by other writers, at least where it concerns the fictitious confrontation between Japan and the U.S. But Crichton's attempt to splice a "serious" message onto his thriller has stirred up a sizable controversy. Considering his approach toward Japan and the Japanese, it's not difficult to see why. Prompted by the lively criticism, Crichton ascended a public forum and tried to justify what, and why, he wrote. At this forum, a June 5 symposium sponsored by the Japan America Society of Southern California, Crichton explained and defended his rationale for Rising Sun in a presentation called "America Bound and Gagged: Political Correctness and Censorship of the U.S.-Japan Relationship." Crichton said his aim was "to provoke a discussion of ... economic issues," that he claims "was not taking place." To this end, he chose "to do a thriller about our unrestricted sale of high-technology companies to foreign competitors." Japan warrants the brunt of this criticism because, by Crichton's reckoning, Japanese companies have accounted for "two-thirds of high-tech sales since 1988." "The book has a strong voice," he continued, "because I am upset about what has happened in America, and what we have done to ourselves." Crichton also stated that he wrote Rising Sun "knowing that it would be attacked." He then proceeded to lash out at those who criticized his book for employing racial stereotypes without bothering to scrutinize the economic issues he supposedly raises. He also offered specific responses to what he feels have been the four main complaints by the book's critics. These complaints were, in his words:

Crichton evaded the issue of certain controversial passages that appear in his book by insisting that his critics are driven by ideology, and by suggesting that "the novel is a Rorschach inkblot in which the critics have seen whatever they want to see." "Calling me a racist," Crichton pleaded in his presentation, "does not address the economic issues I raised." Such terms as "racist" and "Japan-bashing" aside, however, too many things in the book have nothing to do with economic issues. Why, for example, does Crichton pick at old scabs through references to "terminal medical experiments in Japan" during World War II and "stories about the Japanese feeding (American) livers to subordinates as a joke" (p.123)? And why such remarks as "the Japanese are the most racist people on earth" (p. 219), and "I have colleagues who say sooner or later we're going to have to drop another bomb. But I don't feel that way. Usually." (p. 230)? In virtually all other novels of this genre, Japanese literary villains are tagged with a distinct identity -- unrepentant rightwing neofascists, brutish yakuza or irradiated, psychologically scarred A-bomb victims with a hatred of America. This technique helps give such fiction the thrust it needs to carry readers' interest. Here, at least, Rising Sun sharply diverges from other works. Rather than assigning his Japanese bad guys convincing personal motives for their long roster of supposed misdeeds in America, Crichton indicts the entire nation and its people. Four more pointsBeyond the four criticisms of Rising Sun addressed by Crichton himself, would like to raise four more closely focused objections to the means he employs to advance his "discussion of economic issues." 1. Passages in Rising Sun imply that the presence of Japanese business in the U.S. is malignant and insidious. Best illustrating this implication is the statement by John Connor, the story's central character, that Japanese in the U.S. have created a "shadow world" from which Americans are excluded (p. 57). "You must understand . . . there is a shadow world -- here in Los Angeles, in Honolulu, in New York. Most of the time you're never aware of it. We live in our regular American world, walking on our American streets, and we never notice that right alongside our world is a second world. Very discreet, very private. Perhaps in New York you will see Japanese businessmen walking through an unmarked door, and catch a glimpse of a club behind. Perhaps you will hear of a small sushi bar in Los Angeles that charges twelve hundred dollars a person, Tokyo prices. But they are not listed in the guidebooks. They are not a part of our American world. The are a part of the shadow world, available only to the Japanese." Crichton's character here appears to harbor resentment over the fact that a group of expatriates do not particularly wish to socialize with Americans. This is an old grievance that has been leveled against other groups in the past. In the 19th century, for example, America's Chinatowns were portrayed (especially by Caucasians) as vile, rat-infested havens of crime. Connor's Japanese "shadow world" seems to warn of a similar secretiveness and menace in present times. 2. Passages in Rising Sun foment a sense of deep and abiding hostility between the U.S. and Japan. In one example of this, a policeman whose uncle disappeared in a Tokyo POW camp tells fellow officer Peter Smith, the narrator of the story, that the U.S. is at "war" with Japan, and that Smith, who receives a special stipend to learn the Japanese language, is disloyal (p. 122). "So don't talk to me about hating, man. This country is in a war and some people understand it, and some people are siding with the enemy. Just like in World War II, some people were paid by Germany to promote Nazi propaganda. New York newspapers published editorials right out of the mouth of Adolph Hitler. Sometimes the people didn't even know it. But they did. That's how it is in a war. And you are a fucking collaborator." 3. Passages in Rising Sun exaggerate Japanese power by suggesting their abilities are superior to Americans. Police captain John Connor, who is portrayed as an expert on Japan, makes statements like this (p. 67): "Compared to the Japanese, we are incompetent. In Japan every criminal gets caught. For major crimes, convictions run 99 percent. So any criminal in Japan knows from the outset he is going to get caught." This notion of superior competence and efficiency is designed to wound American self esteem and grate on American concerns. To some readers, though, it may suggest that Japanese do things better than Americans, ergo, over the long run in any transaction, Americans are liable to be victimized by Japanese. 4. Passages in Rising Sun intimate that the Japanese exert a profound and deep influence on the U.S. mass media. For example, a Los Angeles Times reporter remarks (p. 175): "The American press reports the prevailing opinion . . . the opinion of the group in power. The Japanese are now in power. The press reports the prevailing opinion as usual. No surprises." Some readers may see this as suggesting that any U.S. publication that treats Japan in an evenhanded manner must have been influenced, or purchased outright, by Japanese money. Adding it upCrichton's most incredible plea in his own defense at the June 5 symposium was that Rising Sun is really "a book about bad Americans." Of the 62 characters in the book who have speaking roles, he says, 52 are American and only 10 are Japanese; he also points out that the book has five American villains as opposed to only one Japanese. These figures skirt many problems, one of which is that a number of major American characters in Rising Sun express angry, pejorative opinions about Japan and/or the Japanese. In contrast, their criticisms of the U.S. come across in much more diluted strength. If Crichton seriously wishes to assail "bad Americans," I'm happy to offer a few suggestions for his next novel: Begin by tossing in a remark that Americans are the most racist people on earth; mix in a few reminders that Americans committed wartime atrocities against their enemies; then wax emotional about how Americans overseas are clubby and clannish; and if, after these broadsides, they still fail to see the error of their ways, he can always have a character assert that they deserve to be nuked! Crichton's "bad" Americans escape such delusionary charges and fantasized punishments, however, because their only sin is to adopt a what-me-worry attitude while their country goes down the economic drain. In the meantime, though, a dozen or so sympathetic characters (all but one of them an American) mouth a chorus of rigid stereotypes about the Japanese. From this viewpoint, it's illogical to conclude much of anything about Rising Sun, except that Crichton hopes to elicit a rigid response from its readers. Crichton's failure to grapple satisfactorily with the economic and sociocultural issues he raises in Rising Sun, in fact, may offer oblique proof that these issues are too complex to deal with in an entertainment novel. From the relatively simpler yardstick of popular fiction, however, the uncertainty lies elsewhere: Will Rising Sun mark the point in time at which thrillers treating Japan and America as adversaries lost their literary innocence, and instead became components in an ideologically deeper level of conflict? |