The Steamy East

Steamy East themes

By William Wetherall

First posted circa 2005

Last updated 28 July 2024

Themes in Steamy East and related fiction The human condition red in tooth and claw

Themes in Steamy East and related fiction

The human condition red in tooth and claw

All faces of humanity

By William Wetherall

Themes of Steamy East fiction run the gamut of dramatic possibility in the human condition. Most stories are mysteries or thrillers intended to entertain more than educate. Mysteries are today as likely to be written by woman as by men, while most thrillers are written by men.

Mysteries and thrillers alike involve mainly crime and intrigue complicated by romance -- or romance complicated by crime and intrigue. Most crimes are committed by individuals for corporate, family, or personal gain. Some are committed in the name of state against a rival or enemy state.

Thefts of industrial or state secrets or of works of art, and smugglings of drugs, weapons, or people, are likely to leave a body or two in the wake. Such crimes and associated murders are solved by amateur or private detectives, if not by police or other agents.

Some Steamy East stories dramatize the psychological and spiritual experiences of travelers, sojourners, adventurers, refugees, and others who cross national borders into unfamiliar surroundings. The protagonists of these stories are also likely to deal with boy-meet-girl complications, as they learn (or avoid learning) the local language and adapt to local cuisine and toilets.

Asian and Pacific wars

A map of international relations over the past few centuries will show that practically all regional wars are genetically related. The DNA of conflict between, say, Japan and China, or the United States and Japan, is passed from one generation of government to the next.

No conflict between governments -- for that is what all wars between countries come down to -- is born without impregnation and a period of gestation, usually very long. While unforeseen events may alter the course of existing conditions, conflict is always rooted in these conditions, which are created by the thoughts and actions of government powerholders.

Countries are like planets in that the movement of one is affected by the movements of all -- the proverbial "n-body" problem. Japan is responsible for its policies and behaviors regarding China and Korea during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. But what the United States did or did not do, regarding these countries and Japan, had huge consequences for the course of Japan-China and Japan-Korea relations, and contributed to Japan's military expansion in Asia and the Pacific.

This is not to blame the United States for what Japan did over the decades, years, and months leading up to its attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941. It is simply to recognize that the conditions which enabled the Pacific War, however much the war was sparked by a unilateral provocation from Japan, stemmed from numerous multilateral provocations over the centuries.

As a fighting war between Japan and the United States, the "Pacific War" began in 1941 and ended in 1945. As a dynamic set developing conditions, however, the war began no later than the middle of the 19th century, and continues in this the 21st century.

The Pacific War is a "Hundred Year War" -- if one takes as its benchmarks the arrival of Commodore Perry in the Ryukyu islands and then at Uraga at the mouth of Edo bay in 1853, and the signing of the San Francisco Treaty of Peace in 1951. This, however, is to ignore the history of the conditions that existed when Perry arrived, and the conditions that exist today as a result of how the war was formally settled -- or left unsettled.

War as a never-ending story

To speak of the "Pacific War" as an event that lasted four years, from Pearl Harbor to Hiroshima and Nagasaki, is like talking about a pimple only when it bursts and bleeds -- as though its festering and growth, and its healing and scarring, were not also part of the narrative.

The "Pacific War" was fought in the "Pacific Theater" of World War II, the setting of what was mostly a "US-Japan" war -- which is not to forget the involvement of many other countries. The point is that "Pacific" draws attention away from East and Northeast Asia -- particularly China and Korea, but also Manchuria and the former Russian territories of Japan -- the foci of conflict from Chinese, Korean, and Soviet points of view.

Yet the more Sino-centric "Greater East Asia War" or "Second Sino-Japanese War" or "Fifteen Year War" distracts attention from contributing factors -- particularly the presence and behavior of the United States states in Asia and the Pacific over the centuries, decades, and years leading up to Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor.

Nothing quiet on the Eastern front

While the shear scale and intensity of the Pacific War warrants it a central place in regional history, its causes and effects are reflected in all related wars past, present, and future. I am introducing the expression "Asian and Pacific wars" to refer to the entire set of such closely related wars, including:

- The Pacific War as part of World War II, and all contemporary wars in Asia

- All wars that preconditioned World War II in the Pacific and Asia -- including the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-1895, the Spanish-American War of 1898, the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905, World War I in 1914-1918, Japan's military takeover of Manchuria in 1931 and its creation of Manchoukuo in 1932, and Japan's invasion and occupation of parts of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1937,

- All wars that have followed World War II in Asia and the Pacific and are part of its legacy -- including the revolutionary war in China that began in 1927, was put on hold from 1937 to resist Japan, resumed when Japan surrendered to the Allied Powers in 1945, and climaxed in 1949 when communist forces drove ROC to Taiwan and established the People's Republic of China, the Korean War from 1950-1953, and the two wars that embroiled Vietnam and other countries in Indochina from the late 1940s to the mid 1970s.

Chinese revolution and Taiwan Straits standoff

The socialist revolution in China, to overthrow the government of the Republic of China (ROC), directed against ROC's Nationalist Army by the communist People's Liberation Army, continues today in the standoff between the remnants of ROC on Taiwan, and the People's Republic of China (PRC) on the mainland. The revolution began in 1927 but was put on hold during China's feeble resistance against Japan's invasions and occupations of many parts of China from 1937. The civil war resumed when Japan surrendered in 1945, and climaxed in 1949, when PLA victories forced the government of ROC and loyal nationalist forces to take refuge in Taiwan. ROC's retreat to Taiwan left the newly created government of PRC with control and jurisdiction over all of ROC's former mainland provinces.

The United States became deeply involved in the revolution, to the extent of stationing U.S. warships in the Taiwan Straits -- first to prevent PRC from mounting an invasion of Taiwan -- then to prevent ROC from mounting an invasion of the mainland to attempt to regain some coastal territories. Japan at the time was occupied by the Allied Powers and had no diplomatic of military standing, but since regaining its independence in 1952, it has been allied with the United States through a mutual security treaty that continues to allow America to maintain many military bases in Japan. Japan also has considerable military forces, that engage in joint military exercises with the United States in preparation for the eventuality of war across the Taiwan Straits or on the Korean/Chosŏn peninsula.

To the extent that Japan is militarily allied with the United States, it is very deeply involved in the ROC-PRC standoff -- which has the potential of exploding into a regional war that would make the 1954-1955 "straits crisis" look like child's play.

The immediate cause of the continuing standoff is PRC's insistence that the status of ROC is a domestic and not an international issue. Taiwan became an international issue when China ceded the territory to Japan in 1895. It again became an international issue in 1945, when Japan unconditionally surrendered to the Allied Powers, and thereby agreed that it would lose Taiwan, and that Taiwan accepted the demands of the Allied Powers that unwillingness to accept the fact that the People's Liberation Army failed to entirely conquer ROC during the civil war that drove ROC to remove its government from Nanking to Taipei and fallback to the line of defense it established in the Taiwan Straits. But the Allied Powers and the United Nations, and United States as a member of both, are also responsible for the manner in which the standoff originated and developed to its present stage.

The Allied Powers allowed their division over ROC and PRC recognition as "China" for peace treaty purposes, to get in the way of fulfilling their responsibility to ensure that the territorial status of Taiwan was clear. ROC should have been allowed to participate in the San Francisco Peace Treaty. And the treaty should have clearly stipulated that ROC was the successor to Japan's former territory, (1) as the sole legitimate successor to the Ching (Qing) Dynasty, which had ceded Taiwan to Japan in 1895, (2) as the state which had accepted Japan's surrender of Taiwan in 1945, and (3) as the state that continued to exercise control and jurisdiction over Taiwan at the time the treaty was signed in 1951.

The United Nations, for its part, should not have accepted PRC as a member state at the expense of ROC's membership. Many states, including ROC, are also responsible for the UN's failure in 1971 to admit PRC as a member state on the condition that it recognize ROC, and permit ROC to remain a member state on the condition that it recognize PRC -- in the manner that the Republic of Korea (ROK) and the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK) were simultaneously admitted to membership in 1991.

ROC, a founding member of the United Nations in 1945, and an original member of the Security Council, should have been required to resign its Security Council seat, because it no longer exercised control and jurisdiction over the mainland provinces of China. And PRC should have been admitted to membership in 1971 but not allowed a seat on the Security Council until which time it proved to other member states that it was ready to fulfill Security Council responsibilities.

Unfortunately, the United Nations is not an impartial body that acts in the best interests of world peace, but has been at the mercy of the same "cold war" politics that helped set the stage for the Korean War by (1) siding with ROK's claim that it was the only legitimate government on the Korean peninsula, (2) then fueling the war, after it was sparked by DPRK's invasion of ROK in 1950, by joining the United States in its attempt to rescue ROK -- both during the Occupation of Japan by Allied Forces dominated by the United States.

Korean War

The Korean War ended in a truce between the Democratic Republic of Korea in the north and the Republic of Korea in the South. The truce remains tense, however, as the former belligerents -- including substantial US military forces based in ROK and Japan -- continue to face each other across the 38th parallel, the line between the Soviet occupied north and the American occupied south in 1945.

Such a line would never have been drawn had the Allied Powers not agreed -- never mind whose idea it was -- to divide the work of accepting Japan's surrender of Chōsen, occupying the territory, and overseeing the establishment of a new Korean or Chosŏn government. Japan's interference in Korea's affairs in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was partly provoked by rivalries between China and Russia over the control of Northeast Asia. America's early acceptance of Japan's expansionism in East and Northeast Asia also contributed to Japan's annexation of Korea following the Russo-Japanese war.

Vietnam Wars

The first and second Vietnam wars left wakes of conflict in neighboring countries. The American Vietnam War (1964-1975) grew out of the legacy of the French Vietnam War (1946-1954). The French war developed from the manner in which the Japan seized control of Vietnam and other parts of French Indochina from the Vichy French government in 1940, a year before Pearl Harbor -- and from the manner in which Japan withdrew from the region at the end of World War II.

Whether Japan's actions in Indochina were right or wrong depends on whether Japan had less right than France to be there under the circumstances. Such questions were obviously moot to Vietnamese revolutionaries in Hanoi, who felt they had the right to oust, by force if necessary, any government they did not want to rule their country -- including the Vietnamese government in Saigon that remained in power at the convenience of the United States.

Ghosts of the past -- alive and well in fiction

All the above real wars -- and a number of related alternative and imaginary wars -- continue to be stages for political, corporate, family, and personal drama in Steamy East fiction. The ghosts of the past are alive and well on the pages of such fiction -- because the legacies of all past wars continue to affect the course history.

Pacific War sagas

Numerous works of historical fiction feature personal and family dramas against the backdrop of the Pacific War. Most such works feature friendships or romances that cross national or racial boundaries or otherwise define and test the character. Many also involve war-related incidents like Pearl Harbor or Hiroshima and Nagasaki, or the treatment by Japan of POWs or by the United States of Americans of Japanese ancestry and others defined as enemy aliens.

Historical understanding

Works of historical fiction, like non-fictional historical writing, varies according to its understanding of history. I parse historical understanding into the following three categories.

"Actual history" is what really happened -- whether or not the facts are known -- whether or not anyone understands what happened and why. Historical truth is an ideal, something one pursues with the understanding that one will probably never grasp the full scope of events and their causes.

"Orthodox history" is what most people accept as having actually happened and why. Ironically, states feud over their different historical orthodoxies -- witness the diplomatic wars between Japan and PRC, and Japan and ROK, and even PRC and ROK, over how the governments of these countries prefer to narrate their pasts in officially approved textbooks.

"Revisionist history" attempts to revise orthodoxy by imposing different, usually unpopular and controversial, interpretations of what actually happened and/or why. Though "revisionism" is a dirty word to the ears of those who take the veracity of orthodox history for granted, historians are supposed to continually subject orthodox views to credibility tests as new evidence becomes available, or as standards of analysis and interpretation change.

Both "orthodoxy" and "revisionism" in history are motivated by ideology. Orthodoxy in history owes its momentum as much to political authority as to academic integrity. It takes only a change in political wind or academic whim for today's revisionist views of the past to become tomorrows orthodoxy.

Not a few historical sagas set during the Pacific War explore controversial "revisionist" alternatives to conventional or "orthodox" understandings of these wars. How much did Roosevelt know about Japan's designs in advance of Pearl Harbor? What role did Hirohito play in Japan's prosecution of the war? Did Truman's decision to drop atomic bombs on Japan constitute war crimes?

The difference between "historical fiction" and "alternative historical fiction" is that, no matter how extremely the former may attempt to revise understandings of the past, "actual history" as a record of events remains unchanged. Whereas the latter very alters the events, even though it may feature historical figures acting in character with their historical personalities.

Forthcoming.

Alternate futures and pasts

The Pacific War has been the theme of numerous imaginary stories with developments and outcomes that radically differ from those described in factual histories and in realistic historical fiction. Some such stories were written before the war, some during the war, and some after the war, but all share in common an imaginary or speculative plot that alters what is known to have happened.

Future and past alternatives

As a genre of imaginary fiction, an "alternate" or "alternative" history" is a "what if" version of history, in which different conditions and different choices result in different outcomes.

What if Japan had not attacked Pearl Harbor or otherwise provoked a war with the United States and its allies? What if Japan had not only attacked but occupied Hawaii, or major westcoast cities? What if Japan had been victorious at Midway and Guadalcanal? Or beat the United States in its attempt to develop an atomic bomb? Of what if the United States and the Soviet Union had invaded Japan's main islands and divided the country in the manner of Germany and Korea?

By "future war fiction" I mean imaginary stories written in the vein of predicting what will or might happen if current events develop in certain directions, with outcomes that could be ideal, favorable, unfavorable, or disastrous.

By "alternative [alternate] historical fiction" I mean imaginary stories written to suggest what might have happened in the past -- i.e., where we would be today -- if certain historical conditions had been different.

Some futuristic fiction is written so far in advance of the plausible future that it is read as "fantasy". Fiction set too far in the past, before historical understanding is possible, may also be read as "fantasy" or "myth".

Futuristic "utopian" and "peril" or "doomsday" fiction encourges people toward heaven or warns them away from hell. Alternative historical fiction may also feature better or worse scenario outcomes by way of suggesting what could have happened in the past had things been done differently.

Futures in the past

As real history outpaces the period in which a story about a future war (or about the yet unknowable outcome of a present war) has been set, the story will be judged in hindsight with respect to the accuracy of its predictions.

Future war tales which have been outpaced by time may inspire future works of alternative historical fiction. And if one ignores when they were written, such tales may be read as alternative historical fiction.

Stories of peril in various hues are discussed under The colors of peril (defined below) and stories of atomic or nuclear intimidation reviewed under Nuclear threats and blackmail (below). However, all such stories related to the Pacific War and other Asian wars are integrated into the following lists.

Future war fiction

1895 The Yellow Wave (Kenneth Mackay)

1899 The Yellow Danger (M. P. Shiel)

1905 The Yellow Wave (M. P. Shiel)

1907 The Yellow Peril in Action (Marsden Manson)

1913 The Dragon (M. P. Shiel)

1925 The Great Pacific War (Hector C. Bywater)

1929 The Yellow Peril (M. P. Shiel)

1932 The Box From Japan (Harry Stephen Keeler)

1933 The Last of the Japs and the Jews (Solomon Cruso)

1940 Lightning in the Night (Fred Allhoff)

1943 Invasion! (Whitman Chambers)

Alternative historical fiction

1994 MacArthur Must Die (Ian Slater)

2001 A Date Which Will Live in Infamy (Brian M. Thomsen and Martin H. Greenberg)

2007 1945 (Robert Conroy)

2009 1942 (Robert Conroy)

Real and imaginary enemies

Countries at war may restrict or curtail the movements of civilian enemy aliens, or may round them up and confine then in facilities or camps, if not deport them. A country at war may also view its own subjects, nationals, or citizens of enemy ancestries with suspicion, and in may treat them as quasi-enemy aliens, possibly suspending their rights under wartime emergency measures.

In the United States, most foreign immigrants and sojourners who were detained or jailed as enemy aliens, and incarcerated in camps during the Pacific War, were Japanese, though some Germans and Italians were also arrested and confined. However, the United States and Canada also interned most of their citizens of Japanese ancestry, and the United States interned people of Japanese ancestry sent by Mexico, Brazil, Peru, and several other Latin American countries. These governments later acknowledged that they had violated the rights of their Japanese-ancestry citizens for no other reason than racial fear.

Prisoners of war are technically military personnel who have surrendered or been captured, usually on battlefields. But in countries invaded and occupied by Japan during the Pacific War, some civilian "enemy aliens" were essentially treated like prisoners of war.

Prisoners of war

Forthcoming

Enemy aliens

Forthcoming

Internment camps

During World War II, the United States, Canada, Germany, Japan, and other belligerants on both sides of the Allied/Axis divide set up camps in which to intern selected enemy aliens.

In the United States, presidential orders concerning enemy aliens legally embraced only aliens of enemy nationality, but some natural and naturalized US citizens of enemy alien ancestry were also interned or forced to move out of areas considered militarily important or vulnerable.

Americans of Japanese anestry residing in designated westcoast zones were exceptionalized in that, though citizens, they were subject to group (as opposed to individual) exclusions on account of their putative race. Americans of Japanese ancestry in the territory of Hawaii, and in states east of Washington, Oregon, and California, were not interned or otherwise subjected to group exclusion.

J. L. DeWitt, 1943, page 101)

In the United States, provisional facilities set up to gather the "voluntary migration of Japanese" from the West Coast Camps were called "assembly centers" built in the United States for interning Japanese, and Americans of Japanese ancestry, were generally called "Relocation Centers". Provisional facilities, set up to gather internees before transproting them to more permanent facilties, were called "assembly centers" as internment camps were called.

A selection of internment camp stories

Interment camps have been the settings of many fictional and biographical novels, short stories, and novelistic biography, including the following, titles, several of which have been translated into Japanese.

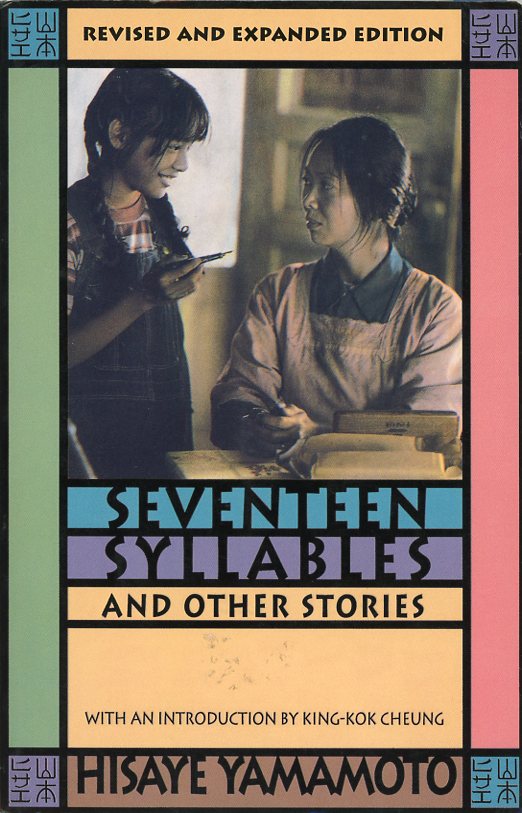

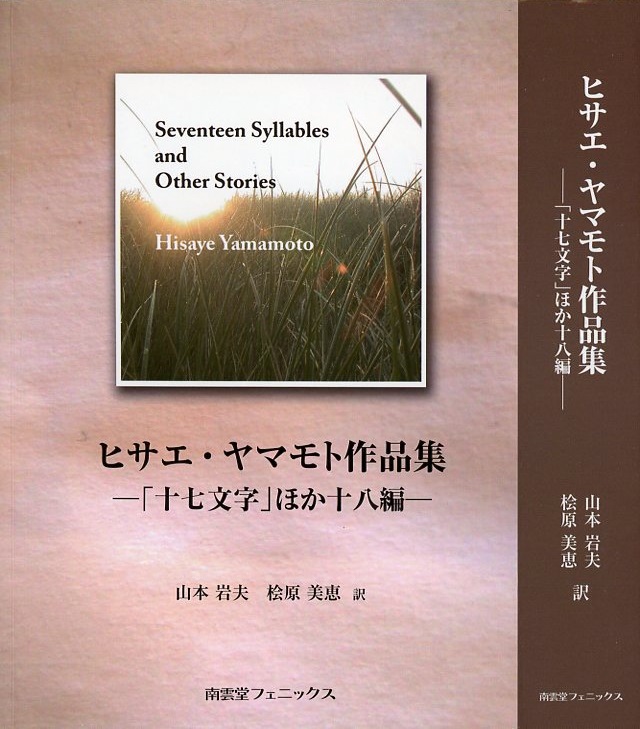

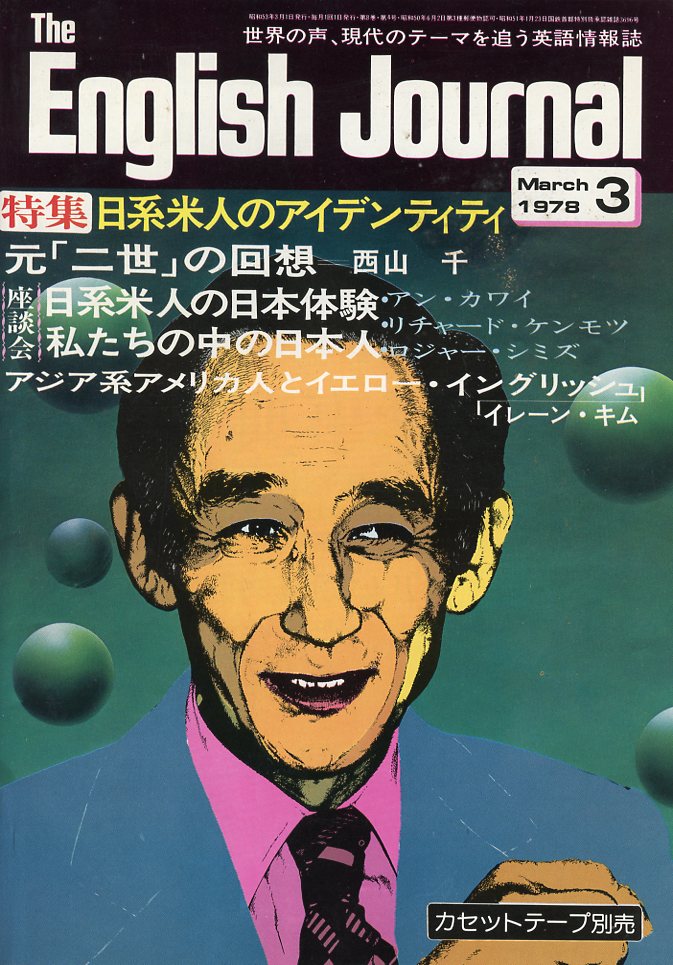

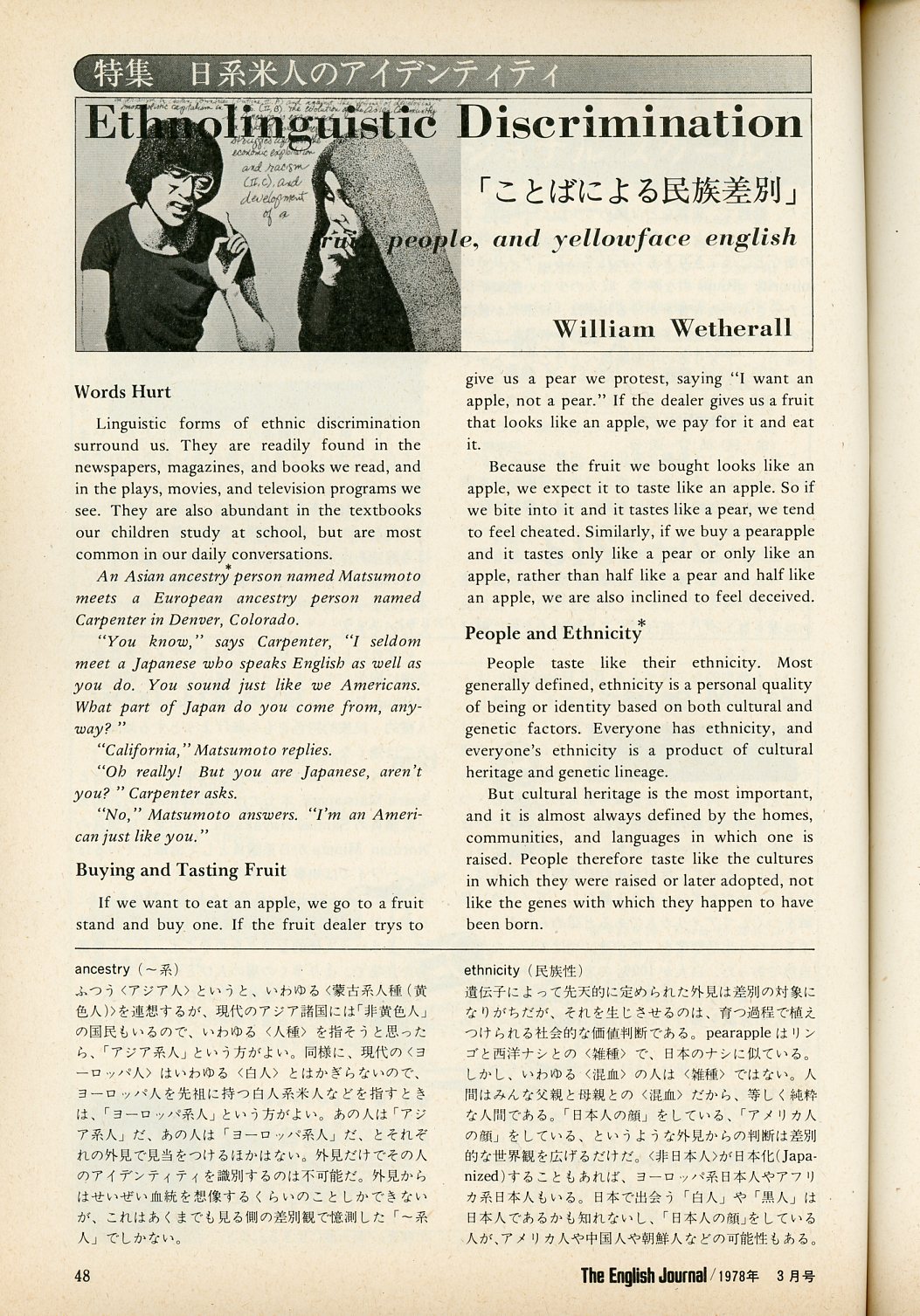

Hisaye Yamamoto 1943"Death Rides the Rails in Poston"Hisaye Yamamoto, born in Redondo Beach, California, in 1921, was interned at the Poston War Relocation Center in Arizona from 1942 to 1945, save for a period in 1944 when she briefly resettled in Massachusetts. She wrote fictional and biographical stories involving camp life and social encounters, both during and after her internment, and her stories have been anthologized in many collections. Yamamoto's first story, "Death Rides the Rails in Poston" (1943), serialized in the camp newspaper, is a murder mystery set in the camp. "The Legend of Miss Sasagawara" (1950) is about a ballet dancer in a Arizona camp, where she is regarded as an oddity. "Pleasure of Plain Rice" (1960) is based on Yamamoto's own attempt to resettle in Massachusetts after her release from Poston in 1944 -- she returns to the camp when learning that the first of her four younger brothers, John Tsuyoshi Yamamoto, had been killed in a battle in Grosetto, Italy, as an infantryman with the 442nd Regimental Combat Team. "An Abandoned Pot of Rice" (1984) portrays the the forced removal of her own family from their home in Oceanside, California., for an assembly center. Her last camp-related story, which I have not seen, was "Reunion" (1992), published like some other stories in the Rafu Shimpo, Yamamoto married Anthony Trevizo DeSoto in New York in 1955. They had 5 children -- Paul, Kibo, Yuki, Rocky, and Gilbert. Anthony, born in 1915, died in 2003. Hisaye Yamamoto Desoto left 7 grandchildren and 2 great-grandchildren when she died in Los Angeles in 2011. Their are are buried in adjacent graves at Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Hollywood Hills, California. "Death Rides the Rails to Poston" in included in the revised and expanded 2001 edition of "Seventeen Syllables and Other Stories". Hisaye Yamamoto Seventeen Syllables and Other StoriesHisaye Yamamoto Hisaye Yamamoto Hisaye Yamamoto Japanese translationヒサエ・ヤマモト <Hisaye Yamamoto> (著) Hisaye Yamamoto (author) "Seventeen Syllables" in other collections and studiesHisaye Yamamoto Hisaye Yamamoto 1975 Asian American Writers ConferenceHisaye Yamamoto was a panelist at the First Asian American Writers Confernce held in Oakland in 1975. The conference was organized by Combined Asian American Resource Project (CARP), which was founded in 1974 by Frank Chin, Jeffery Paul Chan, Lawson Fusao Inada, and Shawn Wong, all writers active in the San Francisco Bay Area at the time, to publish Aiiieeeee! An Anthology of Asian-American Writers that year. The conference was held the following year at the Oakland Colosseum near Lake Merritt. The conference ran for 3 days, and I attended its events while living in Berkeley, where I was packing in preparation for moving to Japan in July. Evening events included a performance of Frank Chin's The Chickencoop Chinaman, first staged in New York in 1972. The first Asian American Writers Conference was held at The Oakland Museum in Oakland, California, from 24-29 March 1975. A number of academic reports have said it was held in San Francisco in 1975 or in Seattle in 1976. The Seattle conference, though, was called the Pacific Northwest Asian American Writers Conference. It was held at the University of Washingon from 29 June to 2 July 1976. But the 1976 conference was clearly inspired by the 1975 Oakland conference. I attended all the general lectures, readings, and panel discussions at the conference, and one evening during the conference I saw a performance of Frank Chin's Chickencoop Chinaman at the museum's James Moore Theater. Should people be treated like fruit?At one of the day sessions I raised my hand and asked what I thought was a vital question. One of the panelists was defending the work of American-born Asian American writers who dwell on their own experiences growing up Americans of Asian ancestry. Someone in the audience argued that Asian American writers should endeavor to nurture awareness of ancestral country heritage, else such awareness to the descendants of immigrants. It came down differences in the vantage point of what I would call "Asian Americanist" writers like Frank Chin (b1940), who was born in Berkeley and raised in Placerville and Oakland, California, and other principal conference organizers, and "Asianist" writers like Jade Snow Wong (1922-2006), who was born and raised in San Francisco. I asked whether the cross of a pear and apple should taste like a pear or an apple, and wondered if it was appropriate to treat people like fruit. My point was that, if I were to pick up a novel by a writer with a Chinese-esque name, and it didn't concern life in China, or the life of a Chinese immigrant who waxed nostalgic about things Chinese, would I have a right to feel disappointed and get my money back? Three years later, I repeated this question in a somewhat different way in an article I wrote for the March 1978 edition of The English Journal titled "Ethnolinguistic discrimination: Fruit, people, and yellowface English" (Tokyo: ALC, Vol. 8, No. 4, pages 48-54). See images to right. |

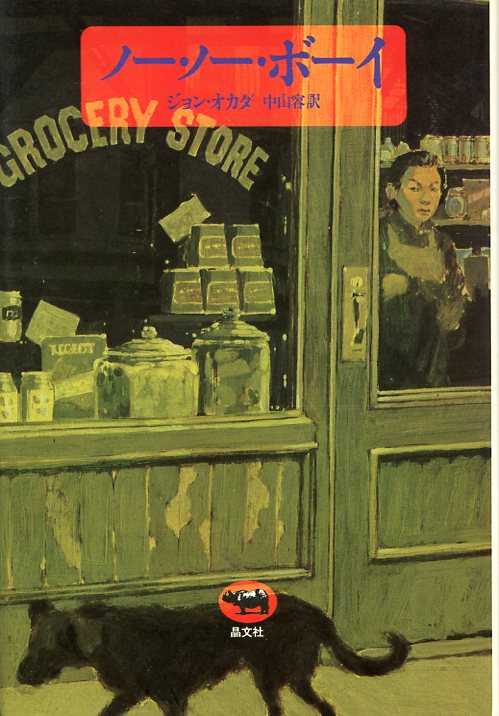

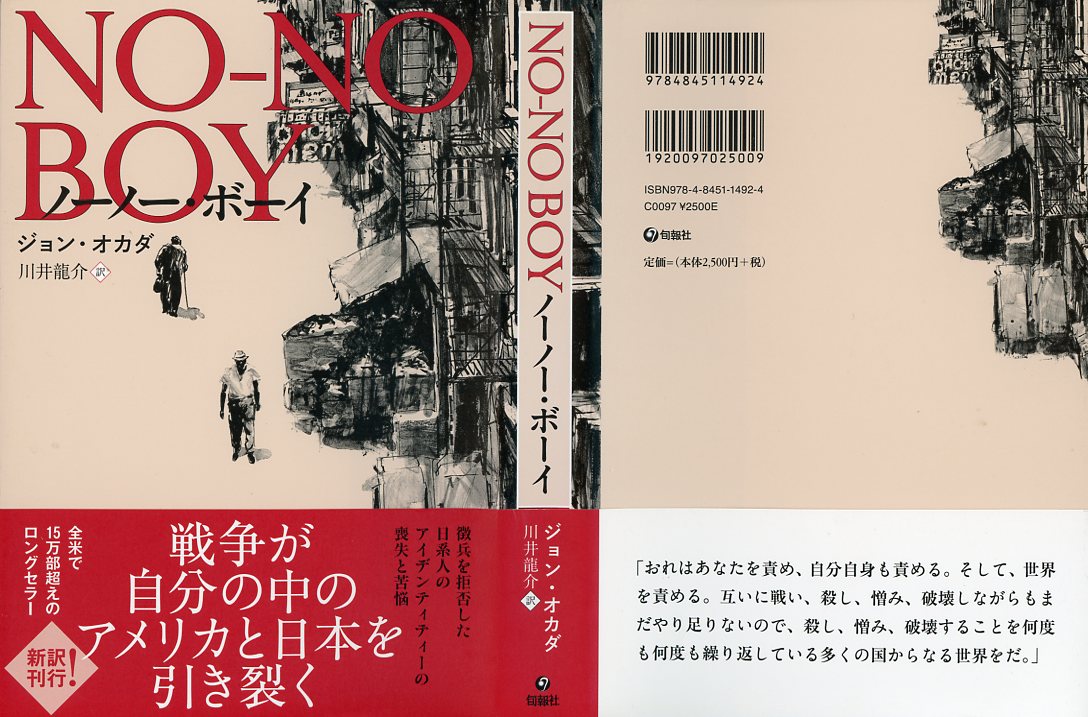

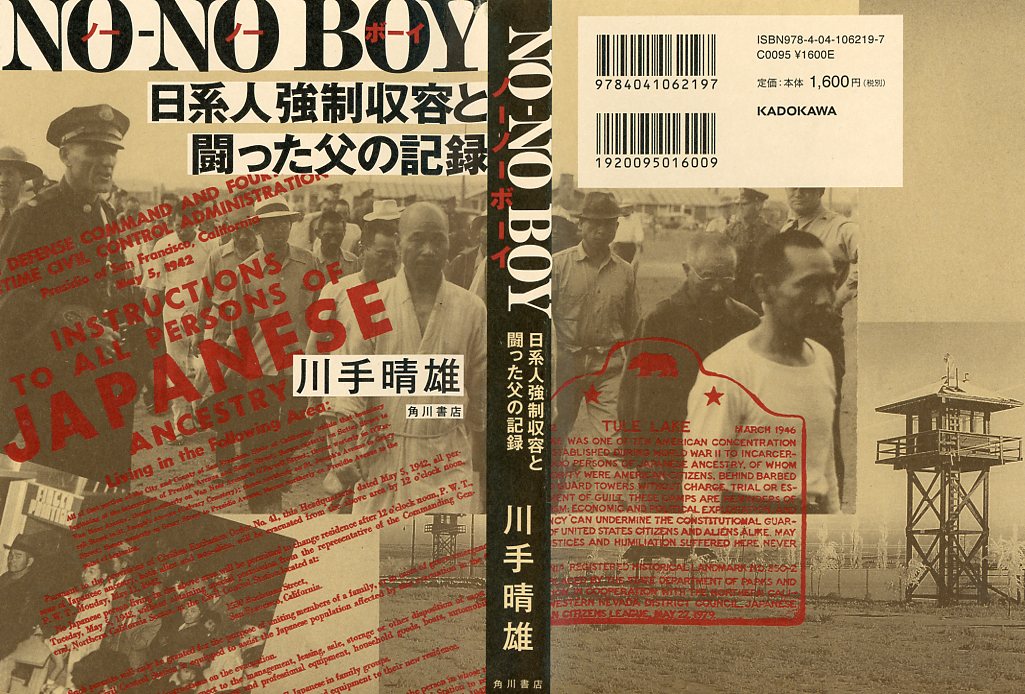

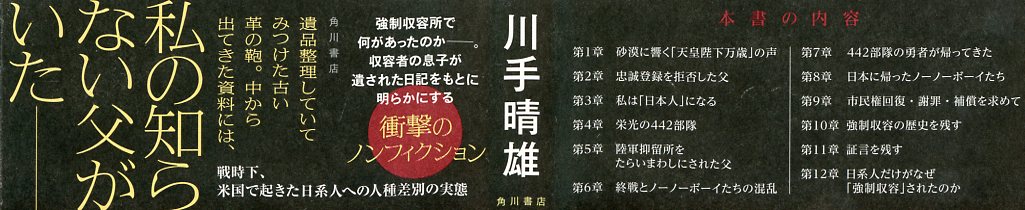

John Okada 1957No-No BoyThis is perhaps the best known work of "classic" Japanese American writing, not only in the United States but in Japan Okada 1957 (1957 and 1976 editions)Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle, 1957 Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1976 Okada 1957 (2014 UOWP editionJohn Okada Okada 1957 (2019 Penguin Classics editionPenguin Classics, 21 May 2019, 240 pages With a new foreword by Ruth Ozeki (Seattle, 30 April 2014) Okada 1957 (1979 Nakayama translation)ジョン・オカダ At least 3 printings were published. Okada 1957 (2016 Kawai translation)ジョン・オカダ Okada 1957 (2018 Kawate translation)川手晴雄 "No-No Boy" in the title is marked with furigana reading "Noo noo booi" |

||||||||||

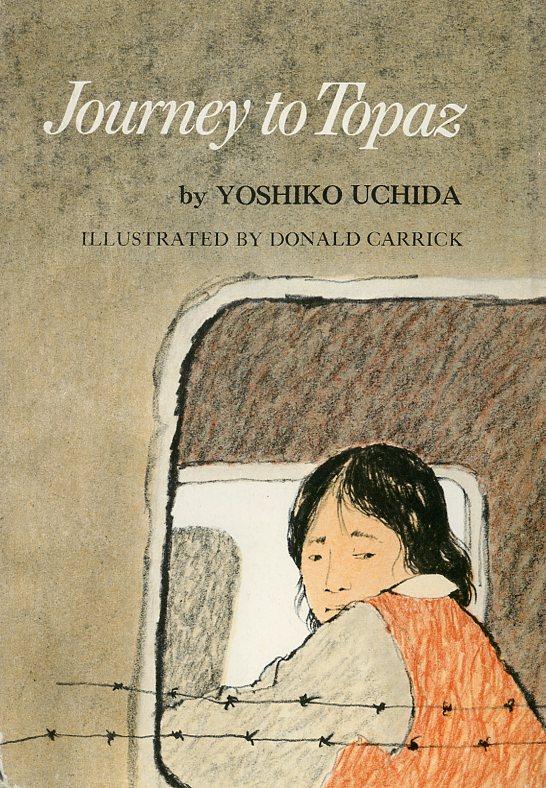

Yoshiko Uchida 1971Journey to TopazYoshiko Uchida (writer) Front flap of jacketLike any eleven-year-old, Yuki is eagerly anticipating Christmas. But the year is 1941, Yuki is a Japanese-American living in California, and the attack on Pearl Harbor by Japan suddenly transforms her entire life. Overnight her parents become "enemy aliens," and Father is taken by the FBI. |

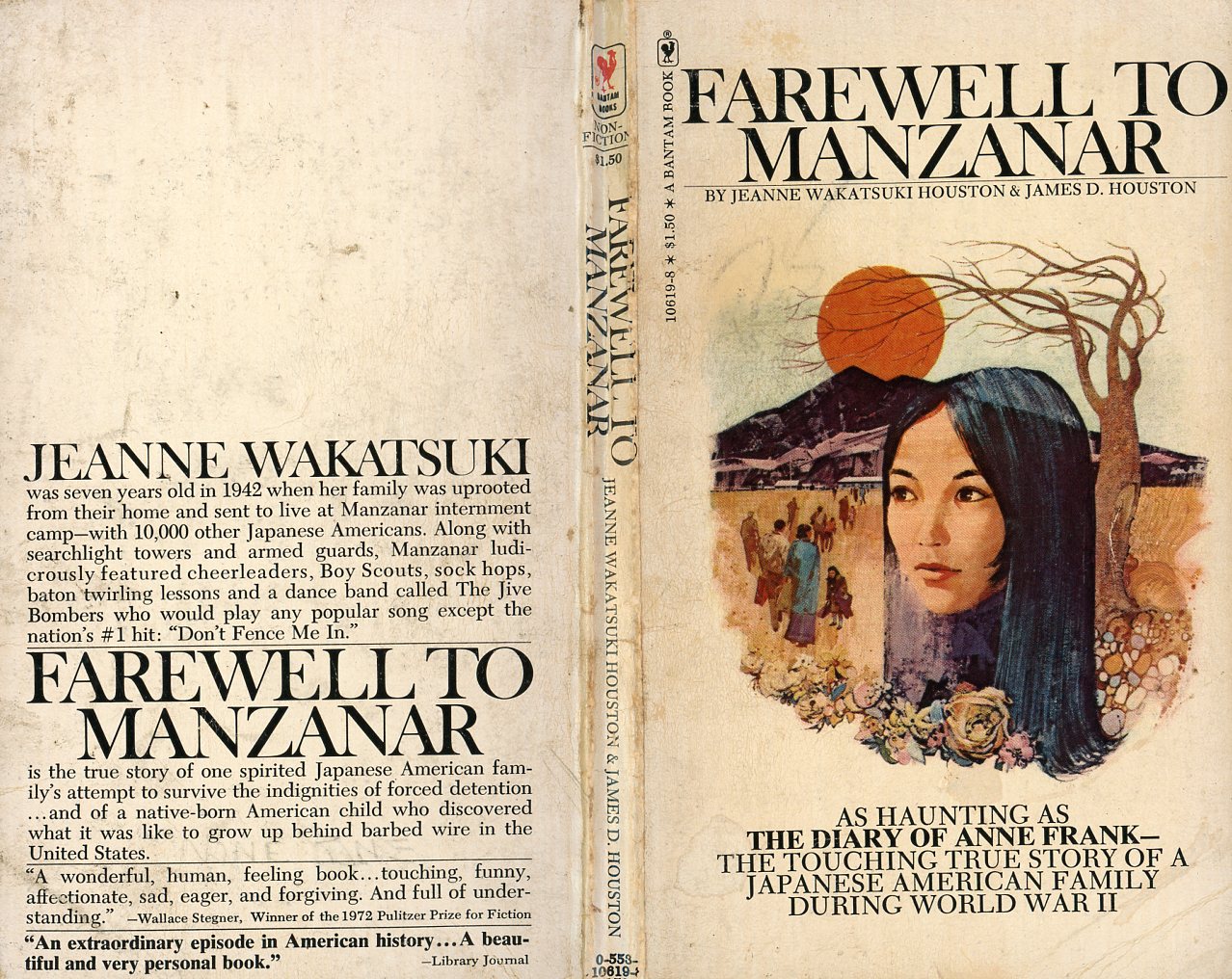

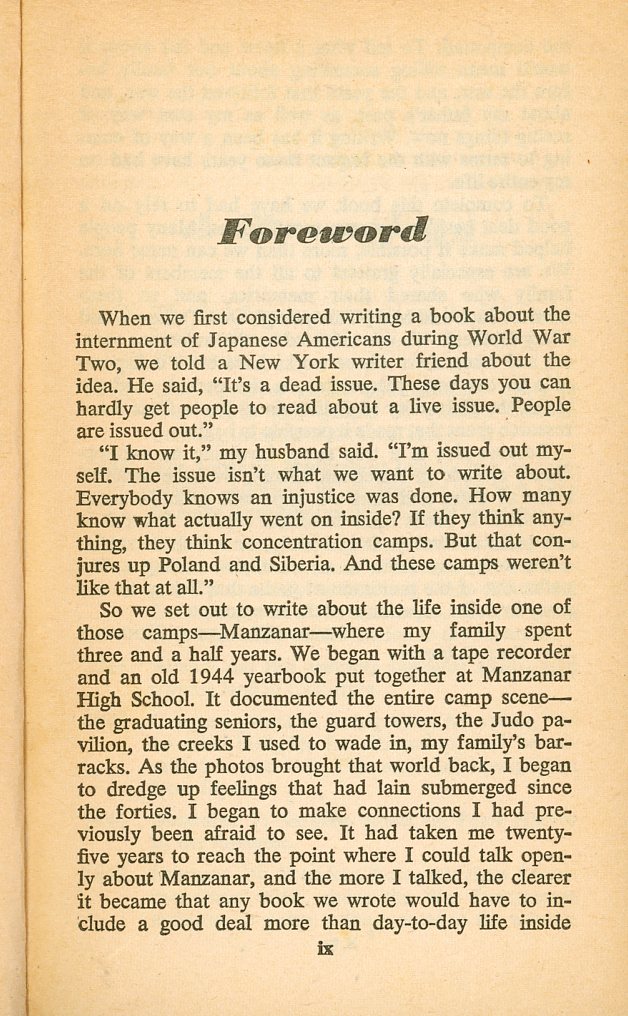

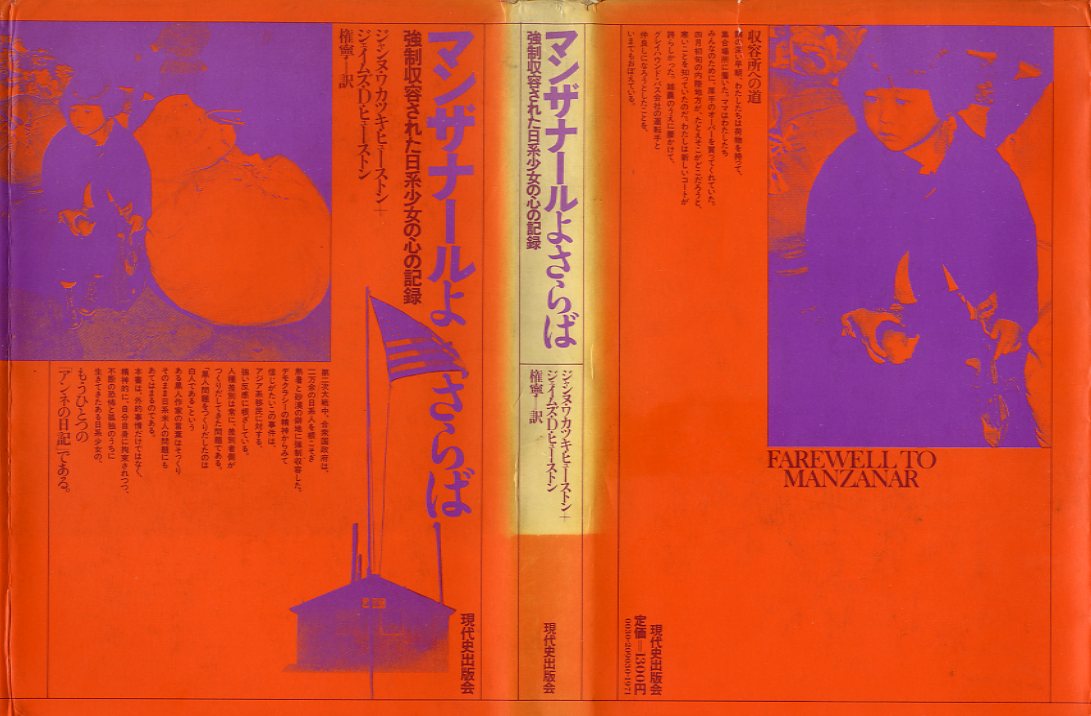

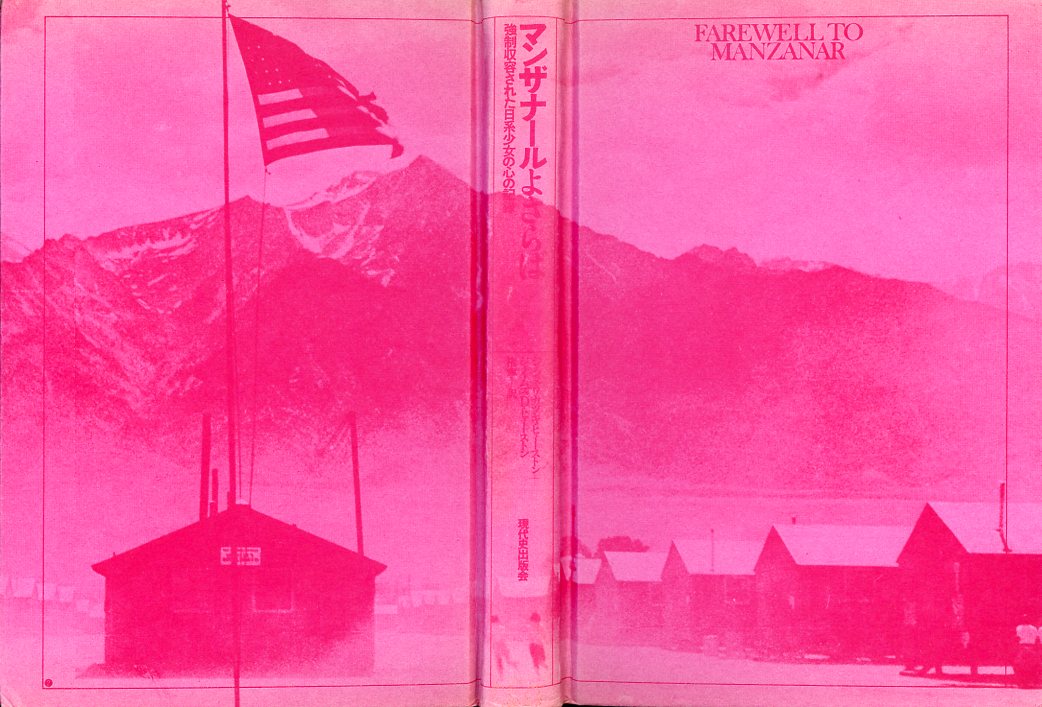

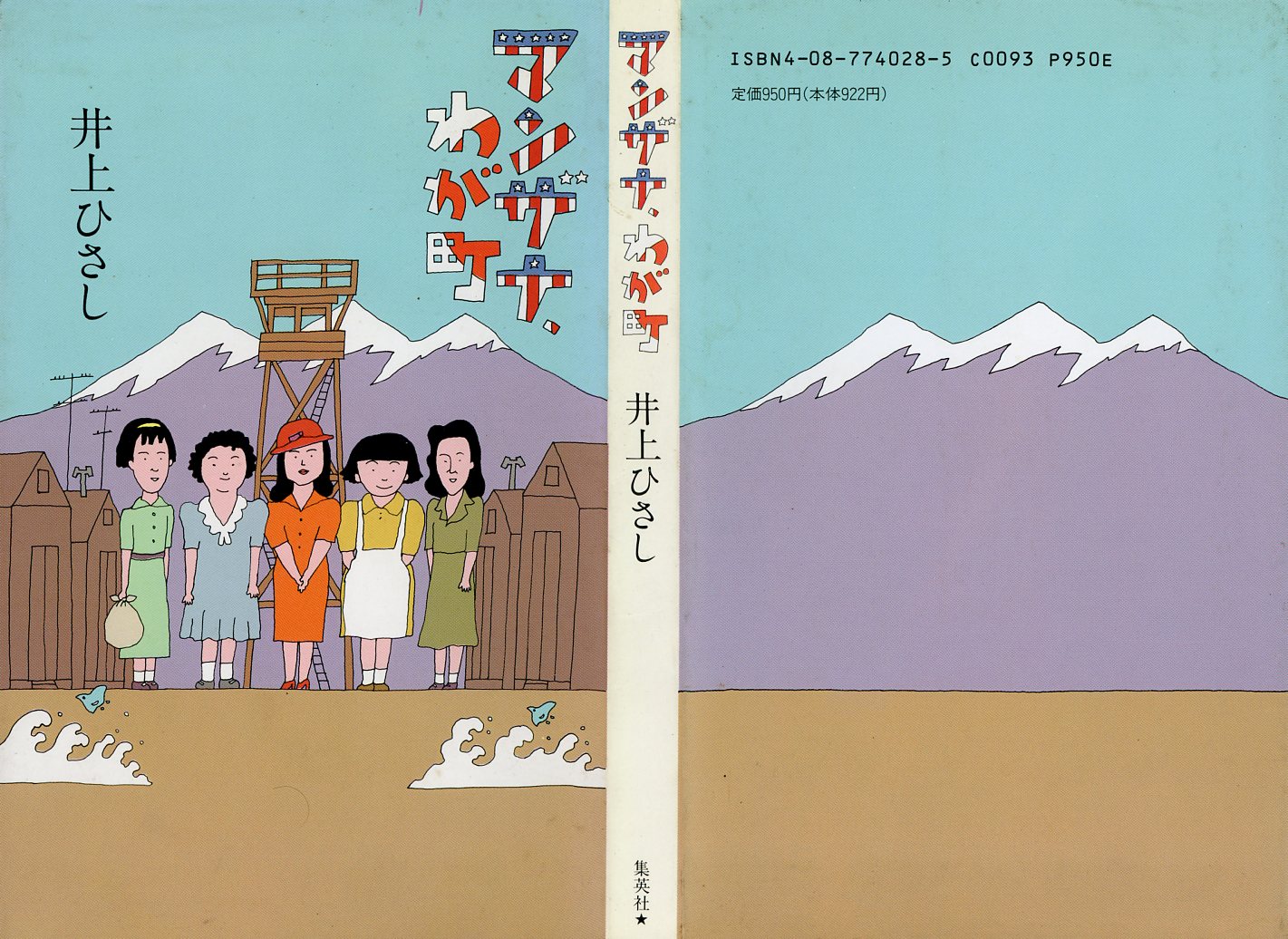

Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston 1973Farewell to ManzanarJeanne Wakatsuki Houston and James D. Houston The back of the dust jacket shows a full page black-and-while portrait of the authors. New York: Bantam Books Bantam published many printings of the paperback edition with at least 3 different cover. The stated copyright holder was James D. Houston (1933-2009), the husband of Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston (b1934). The author profiles in the back say they were married in 1957, had three children, and were living in Santa Cruz, where he was dividing his time between writing fiction, and teaching fiction writing at the University of California at Santa Cruz. At the time, he had published 3 novels. By the time he died, he had written, co-authored, or edited 25 books, most of them involving California. 9 titles were works of fiction, including historical fiction. Farewell to Manzanar was made into a television movie in 1976. The book has been republished numerous times in various editions, some of them specifically intended for use in classrooms, where it has been a perennial favorite on account of its readability and generally accurate and nuanced portrayls of the life of Jeanne Wakatsuki's family before before, during, and after their internment from 1942-1945. The book, translated in several languages, has sold over a million copies, making it the most widely read work of any about the internment camps. Front cover blurbs1973 Houghton Mifflin hard cover editionA moving and intensely human true story -- told with eloquence and warmth -- of a Japanese American family during the internment of World War II and its aftermath. 1975 Bantam Books paperback editionAs haunting as The Diary ofAnneFrank -- The touchingtrue story of a Japanese American family during World WarII 2017 Houghton Mifflin Harcourt paperback editionThe powerful true story of life inside a Japanese American internment camp. 1975 Gon Yasuki translationジャンヌ・ワカツキ・ヒューストン (著) Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston 10 pages photographs, cover, end papers, free endpapers 1993 Inoue Hisaki drama井上ひさし Inoue Hisashi This is a script for a stage play by Inoue Hisashi (井上ひさし 1934-2010), who is a strong candidate for Japan's most prolific and versatile late 20th-century writers, known for his humorous understanding of the human condition. The play was staged 5 times in Tokyo's Kiinokunia Hall from 7-11 July 1993, after which, through 25 July, it toured 6 cities. The playscript was first published in the August 1993 issue of Subaru. In the back matter of the book is a list of 10 principal reference works in Japanese on Japanese Americans and relocation camps, including Karl Yoneda's Manzana: Kyōsei shūyōjo nikki (マンザナ:強制収容所日記) ["Manzanar: Forced detention place (Internment camp / Concentration camp) diary"] (1988). However, he does not list, or otherwise claim to have consulted, Houstons' biographical Farewell to Manzanar. |

||||||||||||||||

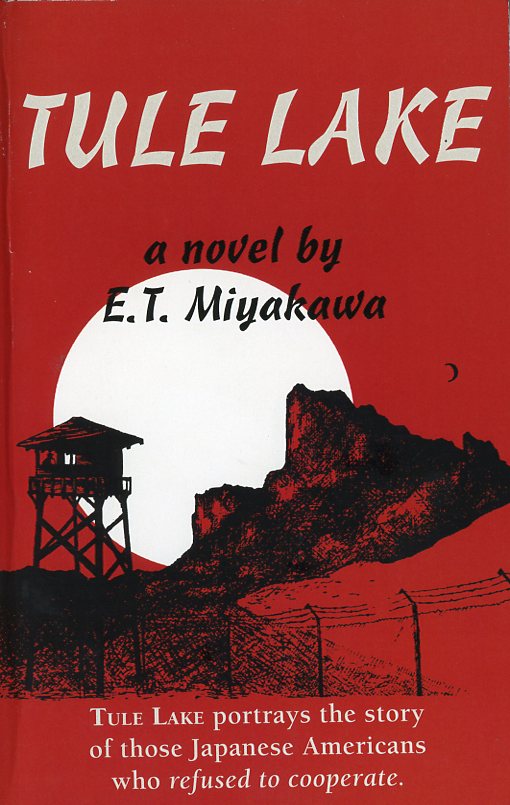

Edward Miyakawa 1979, 2002Tule LakeE.T. Miyakawa (Edward Miyakawa) Back cover blurbTULE LAKE describes the anguish and pain of those men who stood up to Executive order 9066 in order to PRESERVE the Bill of Rights and the U.S. Constitution. About the AuthorEdward Miyakawa was born in Sacramento in 1934. He was raised in the Sacramento area near his mother's parents who farmed in Florin after immigrating from Japan as young adults. The entire family was interned at Tule Lake together, but after a year, Edward's father found a sponsor in Boulder, Colorado where they lived for the duration of the war. After his father attempted to establish the family in Colorado, they decided to move back to Sacramento. |

Robert Davis 1988KimuraRobert Davis This badly narrated novel has the stamp of a story contrived to exploit the popularity of "relocation camp" stories. See Kimura: Commercialized "Japanese Americans" in "Review" section. |

Kirk Mitchel 1988Black DragonKirk Mitchell This is a fairly well-written thriller. See Black Dragon: Learning how to talk to people in "Review" section. |

||||

Cynthia Kadohata 2006WeedflowerCynthia Kadohata Back cover blurbTwelve-year-old Sumiko's life can be divided into two parts: before Pearl Harbor, and after. Before the bombing, although she was lonely, she was used to being the only Japanese-American in her class and she always had her family to comfort her. |

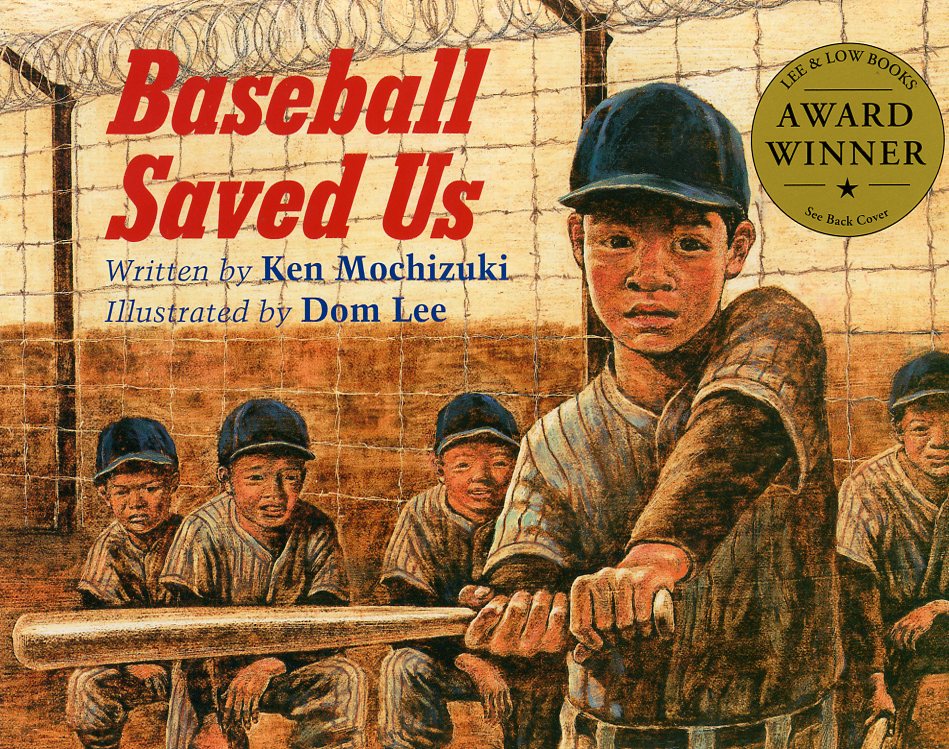

Ken Mochizuki and Dom Lee 1993Baseball Saved UsKen Mochizuki (writer) This picture book tells the simple story of how baseball leveled the racial playing field for Japanese American boys interned with their families in a relocation center during the Pacific War. |

||||

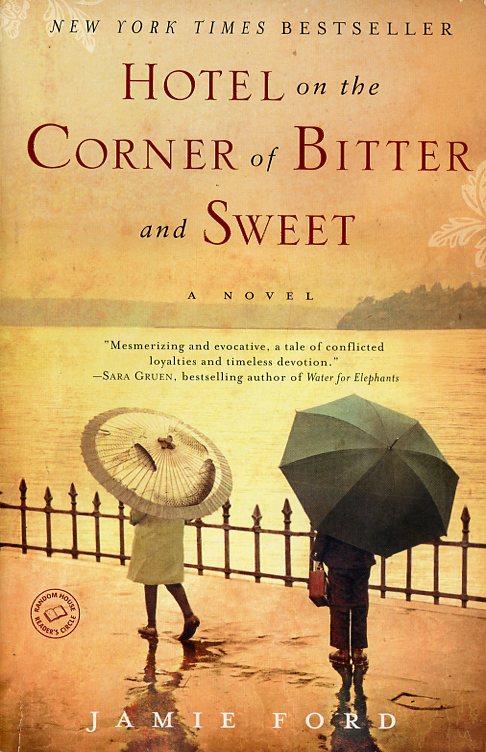

Jamie Ford 2009Hotel on the Corner of Bitter and SweetJamie Ford ジェイミー・フォード < Jamie Ford > The story involves the budding relationship between Henry Lee, a Chinese American boy, and Keiko Okabe, a Japanese American girl in Seattle. Keiko and her family are interned, but Henry continues to correspond with her, until her replies stop coming. Henry ends up marrying a Chinese American girl, and is a good husband. Henry finds out from his dying father, who had been opposed to his correspondence with Keiko, that his father had had intercepted her replies to his letters. Henry is a good husband, and his wife dies, never knowing that he continued to think of Keiko. His son, who hears about Keiko, finds her, and Henry and Keiko meet. Stories about later-in-life reunions between young lovers separated by wars or social conditions are common. This story is particularly interesting, on account of how it dramatizes the tension between Chinese and Japanese immigrants to America, who hope their American children will marry their own kind. Unlike his father, Henry does not object that his son marries a girl who is not a Chinese American. |

||||

Peril and terrorism

Forthcoming.

The colors of peril

Forthcoming.

Atomic bombs

The horrific capacity of a single atomic bomb to evaporate, burn, or radiate so many people and their civilization in a flash -- more than the dispassionate regard of similar or greater levels of destruction by conventional bombs -- account for the shock that many people experience when they learn about what the United States did in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, from the point of view of those who were there to suffer the attacks or witness their results.

There is no excuse for what Truman's decision to drop the bombs at all, much less on populated areas. Yet history records that Japan and Germany attempted to develop similar weapons to those that the United States ultimately developed with the help of German, Hungarian, and Italian scientists who had fled anti-Semitism and fascism, and had warned Roosevelt that Germany might be capable of developing atomic weapons.

Humans, as animals capable of innovating tools and acquiring technology, have always applied acquired knowledge to expand and defend their personal and collective interests. Neighboring populations that fall to fighting over territorial disputes or other differences that spawn conflict do not hesitate to adopt the most advantageous methods of destruction to win wars and survive.

Morality is a luxury when countries become fearful or vengeful. Both sentiments must have informed Truman's decision to use atomic bombs on Japan -- to bring Japan to its knees as early as possible, so as to avoid the necessity of a land invasion -- as well as to further research on the effects of such bombs on actual human targets -- a populated city being merely an object of military attack.

A number of doctoral dissertations and books have been devoted to the topic of atomic bombs and nuclear weapons as themes in literature and film. Some of the more important are as follows.

Nancy Anisfield (editor)

The Nightmare Considered

(Critical Essays on Nuclear War Literature)

Bowling Green (Ohio): Bowling Green State Univeristy Popular Press, 1991

201 pages, paperback

Collection of nineteen articles on different aspects of nuclear weapons in literature. The best overall introduction to the emergence of war fiction involving nuclear weapons.

Martha Taylor Bartter

Symbol to Scenario

(The Atomic Bomb in American Science Fiction, 1930-1960)

The Department of English, College of Arts and Science

The University of Rochester, Rochester (NY), 1985

Ann Arbor (MI): University Microfilms International, 1989

390 pages, xerographic reproduction

Doctoral dissertation

Philip Duhan Segal

Imaginative Literature and the Atomic Bomb

(An Analaysis of Representative Novels, Plays, and Films from 1945 to 1972)

Ferkauf Graduate School of Humanities and Social Sciences

Yeshiva University, New York, June 1973

Ann Arbor (MI): University Microfilms International, 1977

212 pages, xerographic reproduction

Doctoral dissertation

Kyoko and Mark Selden (editors)

The Atomic Bomb: Voices From Hiroshima and Nagasaki

Armonk (NY): An East Gate Book (M.E. Sharpe), 1989

xxxvi, 257 pages, softcover

John Whittier Treat

Writing Ground Zero: Japanese Literature and the Atomic Bomb

Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995

487 pages, hardcover

Nobuko Tsukui

Out of the Ruins: Atomic Bomb Literature of Japan

Tokyo: Ochanomizu Shobo, 2002

235 pages, hardcover

Essays and translations of Japanese women writers on the atomic bomb.

Nuclear blackmail

Forthcoming.

Mingling of races

Forthcoming.

Forbidden fruit

Carnal relations between people who are regarded as being of different races has been controversial in most societies. Controversy, however, has not always resulted in condemnation or criminalization. Some societies have tolerated interracial unions more than others.

A few states of the United States once outlawed sexual relations between the "white" and "colored" races, and legally forbid white-colored marriages. Most such miscegenation laws were dead by 1967, when the Supreme Court favored the the Lovings in Loving v. Virginia and declared Virginia's law forbidding white-colored unions unconstitutional.

on 12 June 1967, after arguments heard on 10 April 1967, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that anti-miscegenation laws violate the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment (Loving v. Virginia, The Lovings, who were from Virginia, had married in Washington, D.C. in 1958, and were charged and convicted of miscegenation after returning to Virginia. The Supreme Court decision struck down (ended the enforceability of) the anti-miscegenation laws in Virginia and fifteen other states where such laws were still in effect though not necessary enforced (Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and West Virginia).

Yet laws do not dictate how people think, feel, and behave. Interracial dating and marriage remains controversial in the racialized communities of all societies.

The Lillian Smith's 1944 novel Strange Fruit originated in a 1937 poem by Lewis Allan (pseudonym of Abel Meeropol, 1903-1986), made popular by a 1939 song by Billie Holliday (1915-1959), in which the phrase referred to a lynched black man hanging from a tree -- "for the crows to pluck . . . for the wind to suck . . . for the trees to drop . . . a strange and bitter crop" (see images and extensive commentary on the in the "Literature" section under "Culture" on the "Konketsuji" website).

More commonly, the phrase "forbidden fruit" refers to pleasure, especially sexual, through the breaking a taboo -- a relationship between people of different races, classes (monarch and maid), or statuses (teacher and student) or with someone of the same sex, or someone who didn't give his or her consent, or a child under the age of consent -- or with someone considerably younger or older, or with a member of one's own family whether a child, sibling, or cousin -- or an extramarital or even premarital relationship -- the list of "forbidden fruits" in the world of literature is long.

To be continued.

Occupation romances

Forthcoming.

1954 And Two Shall Meet (Raymond Mason)

Oriental dolls

Forthcoming.

Travel and adventure

Forthcoming.

Backpackers and sojourners

Forthcoming.

More like them

Forthcoming.

Black samurai

Forthcoming.

White geisha

Forthcoming.

Oriental mystique

Forthcoming.

Chinese boxes

Forthcoming.

Orientalism

Forthcoming.